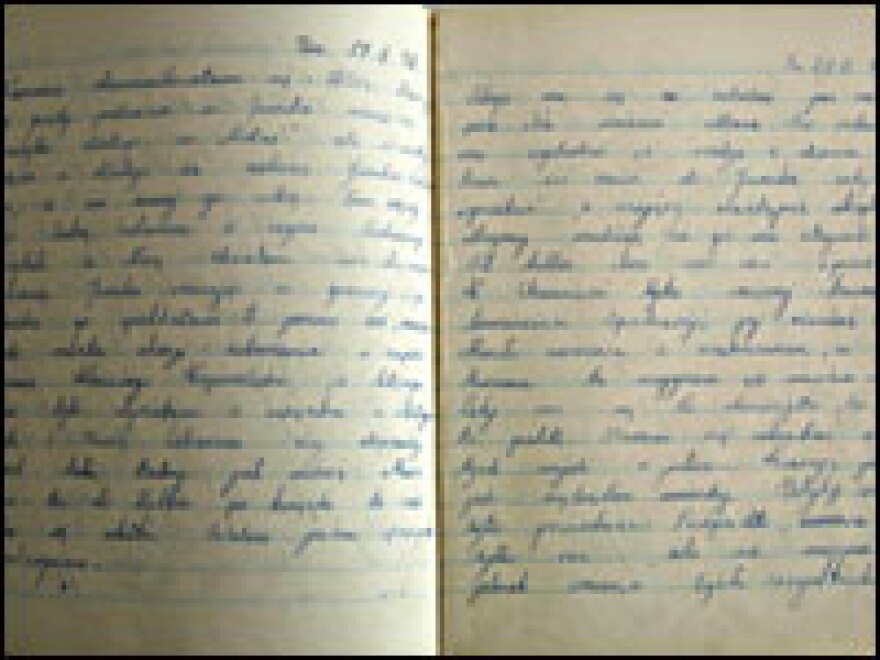

Like many teenage girls, 14-year-old Rutka Laskier kept a diary of her hopes, her dreams and her disappointments. She wrote a lot about boys — the ones she liked and the ones she didn't — and her friends. She wrote in pencil in a spiral notebook, offering a glimpse of life in the Polish town of Bedzin during three months in 1943, under the growing oppression of the Holocaust.

As the Nazis tightened their grip on Poland, Rutka asked her non-Jewish neighbor, Stanislava Shapinska, where she should hide the diary if she had to leave home suddenly. They agreed she should leave it hidden beneath some stairs in Rutka's house.

A 60-Year Secret

When Rutka didn't return after the war, Shapinska went to the hiding place to retrieve the diary, which she kept for more than 60 years. Last year, for reasons that are unclear, the now 80-year-old Shapinska brought it to the Mayor of Bedzin. The diary was first published in Polish, and earlier this month, Yad Vashem, an Israeli group tasked with documenting Jewish history during the Holocaust period, published it in Hebrew and English.

Lia Roshkovsky, of the education department of Yad Vashem, says a personal diary like this one helps students focus on individual lives among the many who died in the Holocaust.

"You have to get the individuals out of the piles of bodies. We don't let them stay in the piles of bodies with no names and no faces," Roshkovsky says.

The Power of Personal Accounts

Bella Gutterman, editor-in-chief of Yad Vashem Publications, says Rutka's diary offers much more than a history book can offer.

"She knew how to describe things. She was very gifted in writing, and the story about her everyday life, such banal things get a special impact when you know she was living under the German rule with the danger. Every day people were missing," Gutterman says. "This is something. You feel like she was talking to you."

In this excerpt dated Feb. 5, 1943, Rutka describes how all of the Jews in her town were being forced to move to a ghetto. Also, Jews were not allowed to leave their homes without a yellow star sewn to their clothing:

"The rope around us is getting tighter and tighter. Next month there should already be a ghetto, a real one, surrounded by walls. In the summer it will be unbearable to sit in a gray locked cage without being able to see fields and flowers. I simply can't believe that one day I'll be able to leave the house without the yellow star. Or even that this war will end one day."

Diaries like Ruska's take on added significance as Holocaust survivors are aging. One day, there will be no survivors left to give first-person accounts of life during the Holocaust.

Yad Vashem is training teachers to use the diary in junior high schools beginning next year.

Lost Faith, Lost Life

Another excerpt from Feb. 5, 1943:

"The little faith I used to have has been completely shattered. If G-d existed, he would certainly not permit that human beings be thrown alive into furnaces and the heads of little toddlers be smashed by the butt of guns."

During the Holocaust, 6 million Jews, among them one-and-a-half million children, were killed. In this diary excerpt from Feb. 20, 1943, as German soldiers conducted a raid, or aktion, in her town, it seems that Rutka had some idea of her fate:

"I have a feeling that I'm writing for the last time. There is an aktion in my town. I'm not allowed to go out, and I'm going crazy, imprisoned in my house ... I wish it would end already, this torment, this hell. I try to escape from these thoughts of the next day, but they keep haunting me like nagging flies. If only I could say, it's over, you only need to die once ... but I can't because despite all these atrocities, I want to live and wait for the following day."

In August 1943, Rutka and her family were taken to Auschwitz. She and her mother were killed immediately. Her father survived the war and eventually moved to Israel, where he remarried and had a daughter named Zahava.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.