Just when you thought U.S.-Russia relations couldn't get worse, diplomatic deals on both Syria and nuclear security fell apart this week.

Moscow went first, announcing that it was pulling out of a landmark agreement on plutonium. Russia's President Vladimir Putin blamed "unfriendly actions" by the United States.

Hours later, Washington said it was breaking off talks on a ceasefire in Syria. "This is not a decision that was taken lightly," State Department spokesman John Kirby wrote in a statement. "Unfortunately, Russia failed to live up to its own commitments."

Moscow and Washington aren't cooperating on much of anything these days. And that prompts a question: What might come next, in the way of cyberattacks?

Russia is suspect-in-chief for recent attacks on targets ranging from the Democratic National Committee to a former U.S. NATO commander to former Secretary of State Colin Powell.

Rob Knake, who until last year served as director of cybersecurity policy for the National Security Council, says the toxic atmosphere might open the door to the U.S. retaliating. Until recently, Knake says, "We would say we want Russia's help on Syria. We want Russia's help on nukes. We want Russia's help on North Korea. Now, we've taken at least two of those issues off the table."

His point: if Russia and the U.S. aren't cooperating anyway, there may be less of a downside to hitting back on the cyber front. On the flip side, Knake argues, Russia may also feel less constrained.

"If they don't have an interest in cooperating with the U.S. in Syria, they may feel free to unleash the kind of attacks that they have yet kept on hold," he says. He sees a real risk of tit-for-tat retaliation spiraling out of control.

Angela Stent, who's watched Russia for many years from perches at the National Intelligence Council and now at Georgetown University, takes a different view, though she agrees this marks an exceptionally dangerous period in U.S.-Russia relations.

"This is the lowest point — it's the worst relationship — since, I would say, before Gorbachev came to power," she says, meaning all the way back to the 1980s, before Mikhail Gorbachev took over as the Soviet Union's head of state.

But Stent is not persuaded this low point will translate to gloves-off, bare-knuckle fighting in the cyber arena. That's because Moscow and Washington still share common interests — including Syria, where Russia and the U.S. are still working together to coordinate counterterrorism operations.

Still, Stent says, Russia will not stop trying to provoke the U.S. with cyber intrusions.

"I think the Kremlin concluded some time ago that this was a lame-duck administration," she says. "And that this was the time to get whatever advantages they can. Because they don't know what the next president's going to do."

Meanwhile, President Obama and his advisers continue to avoid publicly naming and blaming Russia. They cite the ongoing FBI-led investigation into recent hacks.

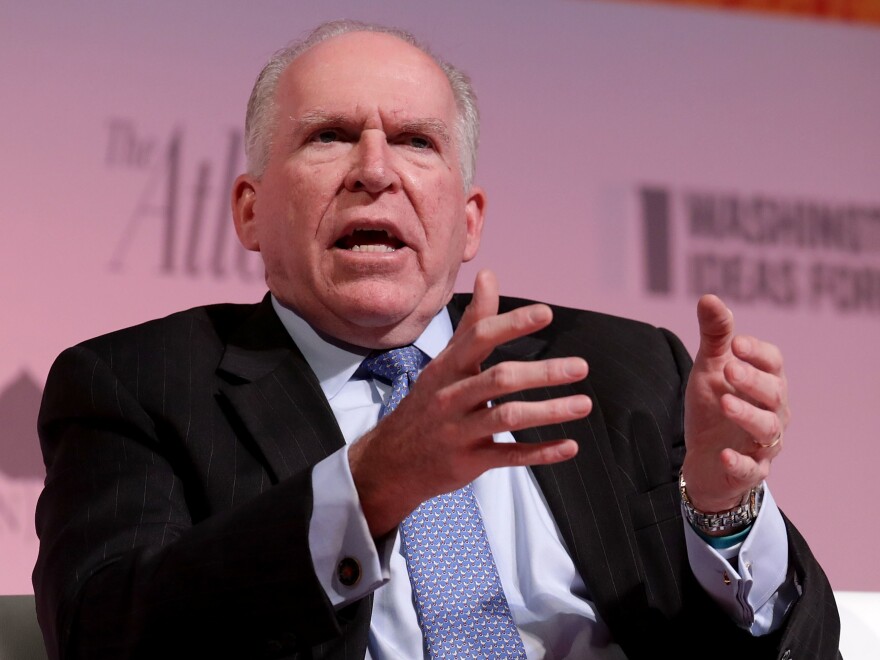

CIA director John Brennan went about as far as any administration official has, in front of a crowd last week at the Washington Ideas Forum.

Asked whether Russia is trying to hack the U.S. election, Brennan replied: "What we do at [the] CIA is to look at a country's capabilities, look at their intent, look at things that they have done in the past, and determine whether something that certainly looks like a duck, smells like a duck and flies like a duck, whether it's a duck or not."

The question now is whether — and how — Washington decides to hunt.

Copyright 2022 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.