Michel Yao says his job is a lot like being a detective.

Yao is leading the World Health Organization's on-the-ground response to the ongoing Ebola outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. And as each new person falls sick, his team must race to figure out how the person got infected.

So, Yao says, "we ask the person a series of questions."

First up: Were you in contact with any sick person who had some symptoms like bleeding or like fever? Perhaps a relative you were taking care of?

No? OK, did you attend a funeral? (At traditional funerals, mourners often wash the body, another way many people are infected with Ebola.)

No, again? Well, then, have you recently touched any dead animals?

But some weeks ago, as cases started erupting around two towns, Katwa and Butembo, the investigators found that patient after patient had something else in common: They had all recently visited a health clinic for treatment for some other disease such as a respiratory infection or malaria.

"They would say, 'I went to the hospital. They treated me. I got clear [of that illness]. And then a few days after, I start having fevers.' " Fevers that were the first of signs of Ebola.

The surge of confirmed cases in Katwa and Butembo – 307 and rising — is now the largest flare-up during the course of this outbreak, which has infected nearly 900 people since August. And WHO officials estimate that in about one-fifth of these recent cases, the person contracted Ebola at health care facilities.

When Yao started visiting the clinics, it was pretty obvious how this was happening: Even government-run facilities such as large hospitals hadn't set up triage tents to separate possible Ebola patients from everyone else.

"This disease is not well-known in this part of the country. It is the first time," Yao explains, even though Ebola has broken out in other parts of the DRC on multiple occasions.

Even more problematic, says Yao, are the hundreds of unofficial private health facilities in this area. Some are large operations. In many other cases, says Yao, "it's just a house — a very old house."

And often a crowded one at that. "In one bed putting two children."

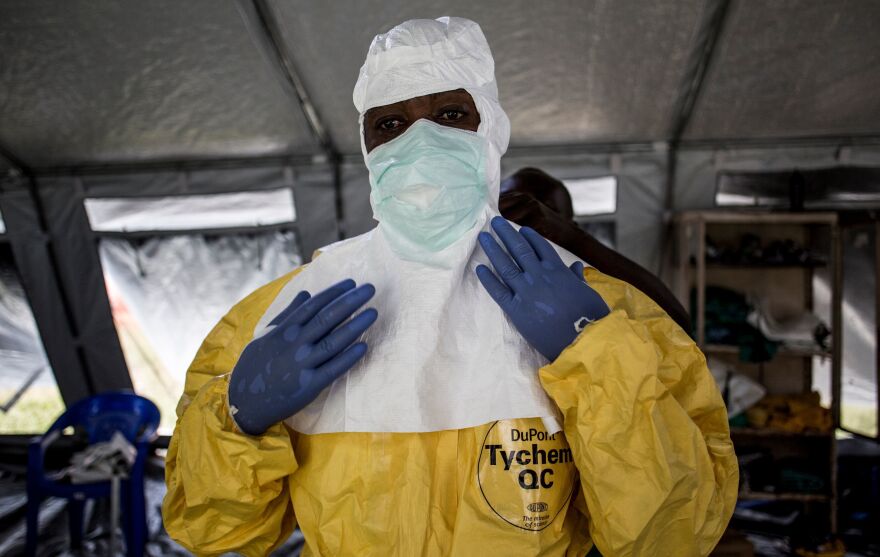

These facilities are also often short on supplies. "You can see people using several times the same gloves or the same equipment," including syringes, says Yao.

Along with modern medicine, many facilities also offer traditional cures. (Indeed, health officials commonly refer to such facilities as "tradi-moderns.") And this too creates opportunities for infection, says Yao.

That's because the traditional medicines are often diluted in water and put in a cup for the patient to drink. Then, he has noticed on his visits, the cup often isn't cleaned before it's passed on to the next patient.

In response to all these findings, Congo's government and the WHO are trying to reach out to every one of these health facilities in Katwa and Butembo. In conjunction with a range of nonprofit aid organizations, they are training the staff on infection control and providing them with necessary protective equipment.

But it's a daunting task. Just finding all the private clinics is difficult because there's no official list, says Yao. Officials know about only the ones reported by Ebola patients.

Dr. Cimanuka Germain of International Medical Corps, which is helping with the effort, says private clinics sometimes resist the help.

For instance, when he told the staff of one clinic that they should report suspected Ebola cases to a hotline instead of treating them, their response was: "This is not possible for us."

That facility treats about 65 patients a day, says Germain. They didn't want to lose business.

Then there's the facility where Germain spent days training nurses on how to set up and operate a triage tent. Two weeks ago he showed up for a surprise visit.

"One of them was there without wearing gloves," Germain says, sighing incredulously.

For Germain the takeaway was clear: "To change someone's behavior is not [a matter of] one day or two days — you need time."

He had been visiting weekly — but from that point on he assigned two people from his organization to keep watch at the clinic all day every day. And he has done the same thing for the 11 other facilities working with International Medical Corps.

Officials are optimistic the watchdogging will work because of the success of similar efforts in a town called Beni — about 40 miles from Katwa. Last autumn, Beni was the epicenter of the outbreak, with the number of cases ultimately topping 200. But over the last three weeks, the caseload there has dropped to nearly zero.

Yao, of the World Health Organization, says improving infection control in Beni's health clinics played a big role in the change. Still, Yao notes, "it took us more than two months to reach these results."

Laurent Sabard, health coordinator with the International Committee of the Red Cross, which has been working with health facilities in Beni, says they can't afford to let up anytime soon.

"We have to continually follow up," he says. If only to ensure they don't run out of supplies. The thermometers given out by the Red Cross are a thermoflash type that lets you take someone's temperature without touching the person, notes Sabard. "But they have to change the battery regularly — so we have to provide them with batteries regularly."

Adding to the difficulty is the insecurity of the area, where multiple armed groups frequently clash with government forces.

Paul Lopodo of Save the Children — which has been working with 39 health centers in the outbreak zone — recalls how back in December the violence prevented the group from checking in with one public clinic for two weeks.

By the time they returned, the staff was so out of practice, says Lopodo, that "we had to the run the training all over again."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.