When photographer Karen Marshall was in her 20s, she couldn't shake the feeling that friendships between women were, she says, "special" and "different." She had grown up in a liberal household in the 1970s, and was surrounded by discussions of women's liberation and consciousness raising. She was finding a lot of meaning in her own female friendships. So she wanted to get to the root of it.

"I remember going to bookstores and trying to think about films I had seen about women coming of age and that kind of thing," Marshall remembers now. "And I couldn't find hardly anything. Like I could find teenage stories, but I couldn't find anything about what women share with each other. So it was pretty specific, just thinking about my chronology, girls in history and even Greek myth, and all that stuff."

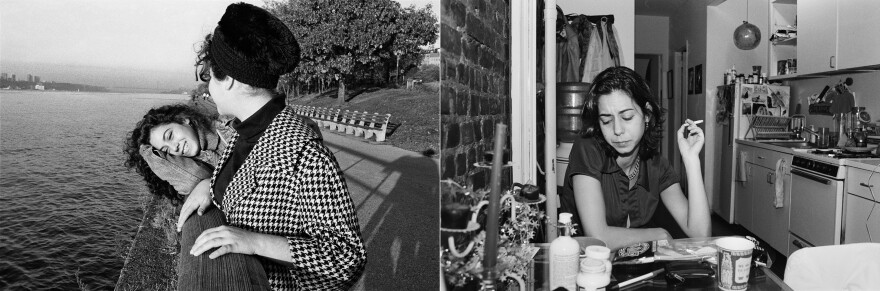

So Marshall decided to create the work herself. After being introduced to 16-year-old Molly Brover, a junior in high school in New York City, Marshall started photographing her and her friends' daily lives. She wanted to catch glimpses of that ineffable bond between teenage girls. She followed them on walks and to parties. She photographed them at diners and at sleepovers. The project began in 1985, and no one could have guessed how many decades it would span, or the tragic event that made the project feel necessary for Marshall.

Ten months into the project, Molly died after being hit by a car while on vacation on Cape Cod. Her death turned the collection of photographs into something heavier and much more personal for Marshall.

"I had lost a friend in high school who actually was my first photography friend," Marshall says. "And that was very emotional. But then I realized that lots of people had. There's this pivotal thing that happens when there's the death of a friend in those teenage years or early 20s. It's like, you're not going to live forever, things can change fast."

Marshall continued photographing the friends through their senior year of high school, and then off and on for years until all the work culminated in an exhibit in 2015, and a book to be released later this year.

She watched their friendships wax and wane, sometimes influenced by the reunions Marshall orchestrated in order to photograph and interview them. Two of the women had a falling out, and one didn't invite the other to her wedding. Reuniting during a session with Marshall only created more tension between them. Later, another friend in the group shared that one of estranged friends was pregnant — a discovery that renewed their bond. And even later still, the newly reunited friends were pregnant at the same time and got to share the experience of motherhood together.

It was a pattern that Marshall recognized in her own life. "I actually knew much better as the years went on in my own life that I had friends that I will call my 'emblematic friends,' " Marshall says. "There are times I might not talk to my best friend from high school for like seven years. And then we have a phone call. And in about three minutes, we actually are on the same page."

The birth of her daughter in 1992 is another event in Marshall's life that brought extra meaning to the project. "There was a day, I'll never forget, when she was probably 14, when two girls came over to our house," Marshall says. "And I looked over, and I was like, this is like a repeat pattern. It's a different generation of girls, and they're doing exactly the same thing."

To Marshall, that moment proved what she'd always suspected and the reason why she started photographing the girls in the 1980s in the first place. "It's part of what I always knew: that this is cyclical, it's things that happen everywhere.

"I do really believe these universal ideas about bonding," she continues, "that even though you could be below the poverty line, or uber rich, or you could be in a very different culture, that a lot of these same things happen — maybe at slightly different times in people's lives, but they happen."

But there's an even deeper reason Marshall spent decades photographing the same group of women, beyond the search for universal truths about emotional bonding.

"When I began, this notion of using documentary photography and visual storytelling as a way to talk about emotional bonding was an abstract concept for a lot of people," Marshall remembers, "because their notion of documentary practice was that something was a conflict or something was how to be about human rights, or something about how to be exotic.

"Things are not just all about conflict," she continues. "And I truly believe that in order to understand who we are as human beings, we have to look at how we get along."

Melody Rowell is a writer and podcast producer living in Kansas City, Mo. You can follow her on Twitter @MelodyRowell.

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.