In 2012, writers who tackled musical topics dove deep, got weird, burrowed into a niche; we joyfully followed them to depths we never would have expected when the year began. We devoured works of criticism, history, biography and the Zen of John Cage and Tony Bennett. While many of our favorite books about music published this year exposed some previously unknown corner of the world, some of the subjects are so familiar already (the lives of James Brown and Marian McPartland, the first four notes of Beethoven's fifth symphony) that the fact that we now have new, authoritative works on them is the surprise. Like the best writing about music, each of these ten books, selected by NPR Music's staff and presented in alphabetical order by author's last name, kept us bouncing between the page and the stereo, reveling in that rare magic of music expressed perfectly in words.

Copyright 2024 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.

Staff Picks: Our Favorite Music Books Of 2012

Life Is a Gift

by Tony Bennett and Mitch Albom

"I don't want to be number one. I just want to be the best."

Of course, Life Is A Gift: The Zen of Bennett, is full of the kind of stories we expect, about jazz musicians like Ella Fitzgerald and Count Basie, full of love for Frank Sinatra (who always called him Kid). But this isn't just a look back. The koans Bennett lists at the end of each chapter reflect the life lessons of a singular artist whose career shows no sign of ever slowing down.

-Felix Contreras

How Music Works

by David Byrne

The title of David Byrne's book is academic, but the way it begins is not. The first word of it is "I." The letter is massive on the page, and the reader realizes that this book is about how music works — as far as David Byrne is concerned. Luckily, he concerns himself with many, many things, from Balinese performance techniques to the acoustics of CBGB, the artistic development of Talking Heads, deal structures and Celia Cruz. It's useful, lucid and funny. He calls music an "organizing principle." Of both learning to dance onstage (he refers to his moves as his body's "grammar of movement") and witnessing racial segregation in audiences and the music business of the early '80s, he writes, "A white nerdy guy trying to be smooth and black is a terrible thing to behold." He includes an eight-step guide to making a music scene. How Music Works reads as if you sat down with David Byrne and didn't interrupt him for a week.

-Frannie Kelley

Shall We Play That One Together?

by Paul De Barros

In Art Kane's famous 1959 photo that has become known as The Great Day In Harlem, pianist Marian McPartland stands next to another pianist, Mary Lou Williams. The pair are so lost in conversation that they seem oblivious to the snap of the shutter that creates one of jazz's most prized artifacts.

I've always wondered what they were talking about, and in his wonderful biography of McPartland, jazz writer Paul de Barros tries to get McPartland to remember what they were so engrossed about. All she could recall was that they were "catching up." The photo is like a family snapshot; de Barros does an excellent job of filling in the details of that lineage with details directly from McPartland, who also went on to become the long standing host of NPR's Piano Jazz With Marian McPartland. It was as a broadcaster that she left her strongest legacy, as she held the same engrossing conversation with every major jazz musician of the last half decade. There, thankfully, we know what was said.

-Felix Contreras

The First Four Notes

by Matthew Guerrieri

Once upon a time, and not so very long ago, entire tomes were devoted to single albums or compositions, from Ashley Kahn's Kind of Blue: The Making of the Miles Davis Masterpiece to Kyle Gann's No Such Thing as Silence: John Cage's 4'33". Now, Boston Globe music critic Matthew Guerrieri has upped the scholarly ante significantly by penning a hefty volume on just four notes. To be fair, this is arguably the most famous string of notes ever written: the duh-duh-duh-DUH of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony. (Actually, the title cheats just a tad; Guerrieri also gives ample space to the rest that precedes the G, G, G and E-flat.) Out of that figure, Guerrieri weaves a wide-ranging, thoroughly entertaining and briskly paced cultural history that wends its way from Napoleon to Klemperer to, yes, John Travolta. (And anyone who namechecks the Portsmouth Sinfonia's infamous mangling of the Fifth as one of eight "interesting" recordings of this masterpiece alongside those of Carlos Kleiber and John Eliot Gardiner is a friend of mine for life.)

-Anastasia Tsioulcas

Where the Heart Beats

by Kay Larson

As its subtitle suggests, the strange and wonderful Where the Heart Beats is a journey through thought and process, not of resulting artifacts. And that feels like exactly the right kind of approach for John Cage, who was as much philosopher as artist or composer. (As Larsen quotes Cage: "My work ... is renunciation of choices and the substitution of asking questions."). Larsen, a former art critic for New York magazine, has written the kind of book that you'll read with one hand and constantly type queries into Google with the other, since her text is studded with references not just to pieces of music but to visual art, Buddhist philosophy and the work of not just of Cage, but of a constellation of his peers and influences, from Marcel Duchamp to Yoko Ono. There are a smattering of regrettable and frankly easily preventable music-related errors (for example, Ara Guzelimian, provost and dean of the Juilliard School, is described as a composer and pianist), but Larsen has a much wider vision — and has therefore set herself with a much more far-ranging task — than the author of a more typical music biography. Her Buddhistic lens on Cage frames a gloriously rich reading experience, studded with layers upon layers of deeply inspiring and endlessly fascinating paths. One of the best books of the year in any category.

-Anastasia Tsioulcas

Why Jazz Happened

by Marc Myers

Aficionados know that any work of jazz history worth its salt is also a work of American history. Racism, protest, demographic shifts, technological intervention, economics: It's all there, and with a better soundtrack. That's why Marc Myers' Why Jazz Happened feels important. In telling the story of musicians' union strikes, or the suburbanization of Los Angeles, or the Civil Rights Movement, the author connects the dots to major stylistic changes in the middle of the 20th century: bebop, cool jazz, free jazz, and so on. It's a readable, relatively slim volume an academic can appreciate, being sourced with lots of Myers' original interviews. But any casual history buff or random dude who owns a Miles Davis album would dig it too.

-Patrick Jarenwattananon

Will Oldham on Bonnie "Prince" Billy

by Will Oldham and Alan Licht

Friends who saw me carrying this book groaned at the title, assuming that what lay inside was some kind of self-hagiography. In fact, Will Oldham on Bonnie "Prince" Billy is an interview — the longest and most incisive ever done with the press-shy songwriter and actor. And if anything, the book makes a man, not a myth, of its subject, by putting him in conversation with a good friend who happens to also be a good journalist.

Alan Licht's years as a musician and Oldham collaborator empower him to ask questions an outsider never would, from completist minutiae (supported, for those who care, by copious footnotes) to big-picture profundity. It's in the latter category that Oldham shines: He's been kicking around the music world long enough to have great stories — say, singing backup on Johnny Cash's cover of his own song "I See a Darkness" — but his thoughts on making and appreciating art spill over with insight. Licht's questions can be paragraphs long, and Oldham's answers can go on for pages, often tumbling into poetic runs (in a riff on country music, he likens the hat-and-boot-wearing superfan to "a wound-up emotional machine waiting to be released by the turn of a phrase"). It's the exact kind of late-night, kitchen-table discourse you'd expect from two creative minds with mutual respect to spare.

-Daoud Tyler-Ameen

Ernie K-Doe

by Ben Sandmel

Much more than a biography of a New Orleans music eccentric, this perspicaciously researched book encapsulates the spirit of a city that honors the wisdom of its weirdos. It's also the story of a unique place — K-Doe's Mother-In-Law Lounge, the shrine to his career-defining hit, and a haven for connoisseurs of this precious city's flamboyant expressive culture. Packed with rare photos and gorgeously produced by the Historic New Orleans Collection press, this volume will transport you to the liveliest city in America — a trip all music fans should frequently take.

-Ann Powers

The One

by R. J. Smith

You want him to start with the music, of course, and then reverse engineer the life as images that flicker brightly over the songs than seem like foundations for everything we hear today. Instead, RJ Smith builds Brown's own world brick by brick. (Starting, just to give you full context, with the drumbeats that accompanied a slave rebellion in 1739.) There's so much history and research in this biography of James Brown that you get the foundations of Brown's music — work, anger, survival and revolution — before a note of it is alluded to.

Then the beat drops, and Smith tracks Brown's ascent — his backbreaking work ethic (on a typical tour in the late '60s, his road manager recalls, Brown and his band played 37 shows and a recording session in 11 days), his indulgences, the famous demands on his players (which ran from outlawing extra-musical hobbies to helping conceal Brown's many extramarital liaisons) and the way his music refracted and engaged the racial politics of the time. His take on Brown's life is so dizzyingly comprehensive, layered with musical and personal meaning, that it's hard to believe the monumental The One is as short as it is, but there's a roaring beauty in its clear-eyed, razor-sharp efficiency.

-Jacob Ganz

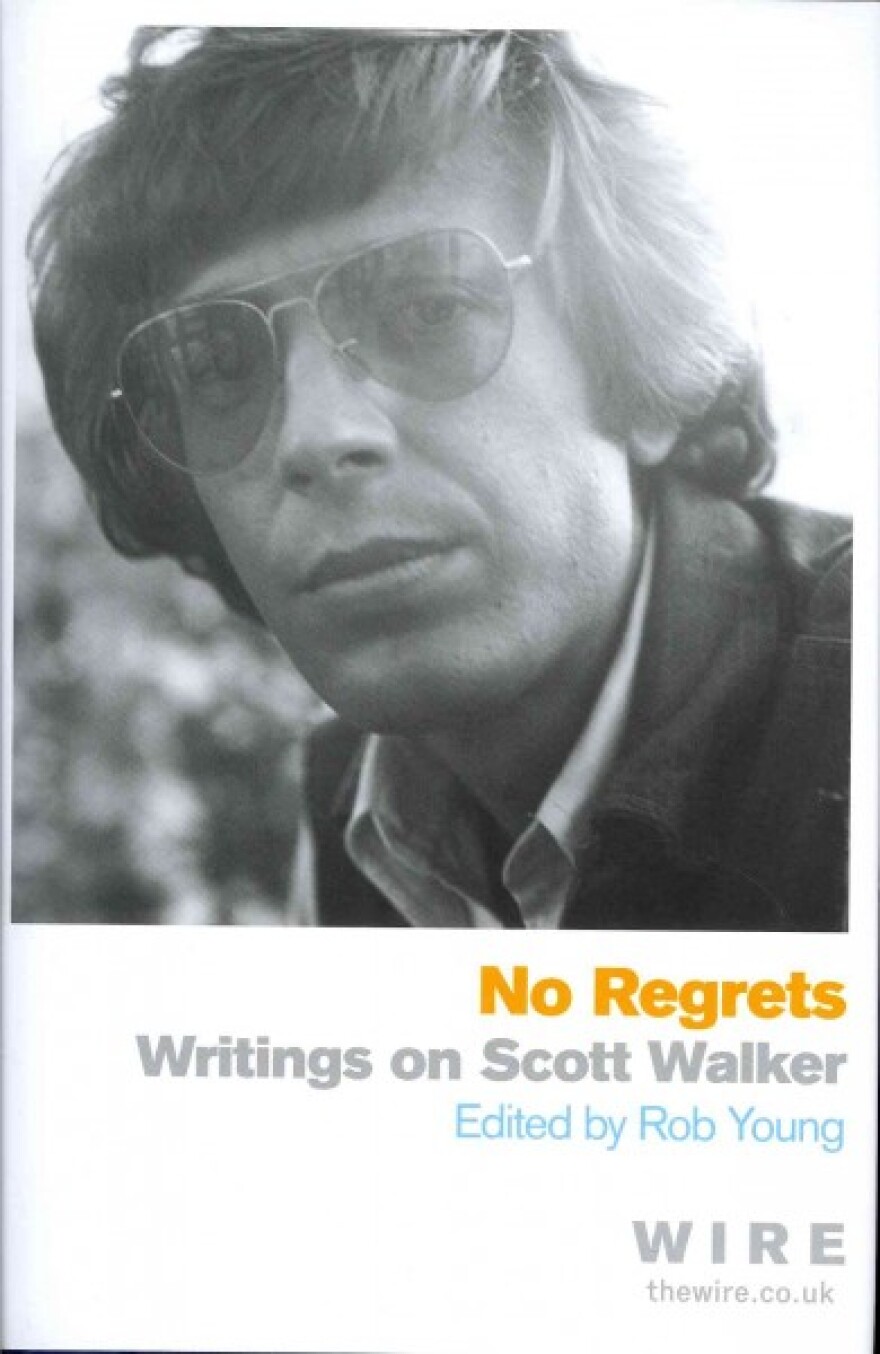

No Regrets

by Rob Young

How do you write a book about a musician who, until very recently, only gave interviews, oh, every 10 years? And, perhaps more unhelpfully, whose work regularly defies standards even as he sings them? No Regrets: Writings on Scott Walker collects a chronological series of essays commissioned by The Wire about the enigmatic musician, picking apart and making connections from old interviews, friends and band mates, and, most of all, Walker's ever-evolving and intensely referential lyrics. From the existential crooner's teeny-bopper days in The Walker Brothers to the challenging blocks of sound on his 2006 album, The Drift, the writers here leave nothing unexplored. Even Walker's frustratingly schmaltzy '70s period is given a reevaluation with an equally frustrating, but no less insightful essay.

-Lars Gotrich