When President Emmanuel Macron set out to overhaul France's notoriously rigid labor laws last fall, unions promised crippling strikes to stop him.

All of France, it seemed, was waiting for the showdown.

After all, the country's powerful unions have stopped French leaders from overhauling their cherished work code for decades. In 2016, a succession of strikes and 14 nationwide protests snuffed out President François Hollande's hopes for simplifying the 3,000-page employment code.

Yet just months into the new presidency, Macron sped through the kind of labor changes many of his predecessors could only dream of. The few marches against him were sparsely attended and soon petered out.

The government's next move is to tighten the unemployment benefits system and overhaul the state pension program — and no one is expecting major resistance.

We're no longer able to bring tens of thousands to the streets with a single call to strike.

Even the economy is going Macron's way. Along with a global growth trend, France's gross domestic product expanded 1.9 percent in 2017 — the highest in six years.

Still, the country's unemployment rate is high at 9.2 percent, above the eurozone average, according to new figures from the European Union's statistics office. Macron is banking on his reforms triggering job creation.

Businesses in France long complained they could not expand because it was too hard to get rid of workers if they needed to. Macron's law makes it easier for companies to hire and fire. It puts a cap on damages for which fired workers can sue their former employer. It also takes away some of workers' collective bargaining power, by enabling managers and employees to negotiate workplace rules company by company — bypassing national unions.

Firing power

Just a couple of months after the changes, businesses are already exerting their new power to fire. And they're no longer legally required to justify layoffs by showing financial difficulty.

French carmaker Peugeot plans to eliminate 1,300 workers, using Macron's new rules for voluntary redundancies, and the company reportedly says it could hire just as many more — mostly younger employees with digital skills. Carrefour, the country's biggest supermarket chain, plans to let go of 2,400 workers.

Pierre Boisard, a sociologist who studies unions and employment issues, says Hollande's and Macron's situations were entirely different.

"Hollande tried to make these kinds of changes at the end of his term. And they were not in his platform, so he had no legitimacy," Boisard says. "Macron campaigned on revamping the French economy."

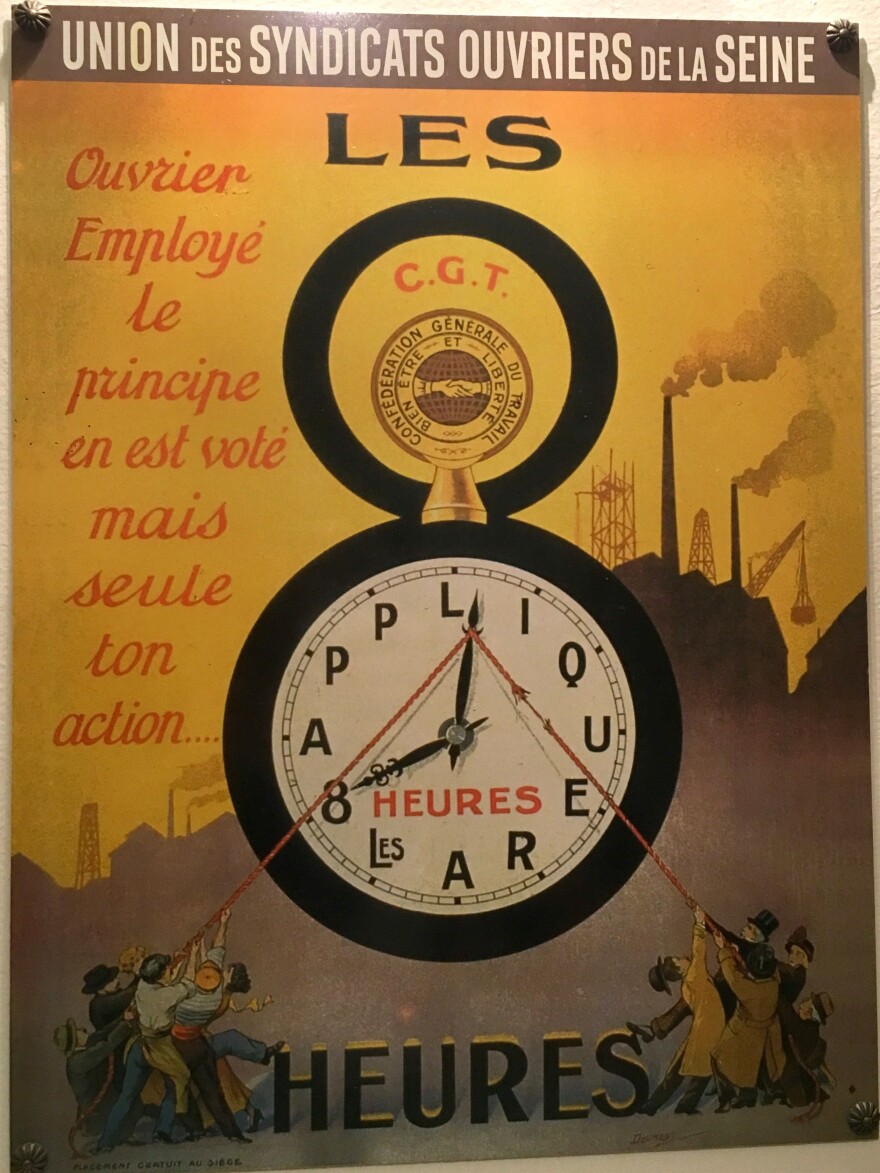

Philippe Martinez, head of the hard-line General Confederation of Labor union, or CGT, admits Macron won the first round.

"But it doesn't mean the French approve of what he's doing," says Martinez, speaking at his headquarters in the Paris working-class district of Montreuil, during a recent meeting with the Anglo-American Press Association of Paris. Several polls last fall showed nearly 60 percent of French respondents didn't support the labor reforms.

But the president's popularity has increased since last fall. Martinez reckons the boost won't last. Like most of the president's detractors, he doesn't believe Macron has a mandate.

"He was elected by default," says Martinez. "Not because voters chose him, but because they were eliminating other candidates." Martinez is referring in particular to far-right National Front leader Marine Le Pen, who faced off against Macron in the final round of voting last May.

Macron won with more than 65 percent of the vote. Then in June, his new En Marche! or "Onward!" party swept legislative elections and now holds a significant majority in parliament. Today no one can deny there is a big mood change in France.

Macron, a 40-year-old former banker, arrived just when French voters wanted to upend the political status quo. "He appeared at a time when the French were totally exhausted with the political forces that have governed this country for the last 40 years," Boisard says.

French billionaire Xavier Niel backs the president and his reforms plan.

"The mere fact of having a young, dynamic, pro-startup, pro-entrepreneur president who is not tied to any of the old political parties is huge," he says.

Niel, a telecom tycoon, pumped about $300 million of his own money into an old train depot, turning it into an airy, 366,000-square-foot hub for startups.

Station F is across town, and a world away from the Soviet-style, cinderblock headquarters of the CGT. What's being called the world's largest startup campus has attracted 1,000 startups and 3,000 entrepreneurs from around the world since it opened in June.

Niel says France's anti-business image was always worse than the reality. He says Macron is improving both.

Slim union rate

Sociologist Boisard says the power of the unions to quickly organize hundreds of thousands of strikers and protesters has been blunted. "Many people are even wondering if the unions' power may be gone for good," he muses.

Though French unions may seem hugely powerful, judging from their perennial strikes and marches, France actually has some of the lowest union membership rates in Western Europe. Only 11 percent of French workers were unionized in 2013, according to the most recent Labor Ministry data available on the subject. That's down from over 30 percent of the workforce in 1949.

Many people are even wondering if the unions' power may be gone for good.

But unions still hold power in prominent sectors like transportation and utilities. So when workers take action, it can cause disruption for the European Union's second-largest economy and grab lots of attention.

Macron once worked as an investment banker, but he's not what the French call a "savage capitalist." The French president says he wants to transform France and develop the country's innovative spirit, but he also speaks of sharing the wealth and protecting workers hurt by globalization.

Before tweaking the labor code, the government held extensive talks with union leaders. Martinez was there.

"I saw Macron more in six months than I saw Hollande in five years," Martinez says. "He understands that you have to at least give the impression of communicating and negotiating. But the truth is it wasn't negotiation, it was more like consulting us. The government listened to what we had to say, but in the end they did what they wanted."

Significantly though, Macron got two other major unions to sign on to his labor law overhaul, leaving the CGT as an outlier.

Martinez rejects the idea that Macron is making France more attractive to foreign investors. He says his country was already attractive.

When CEOs vaunt the advantages of France to foreign investors, he says they point to the same attributes celebrated by unions. "They say France has reliable and good roads and rail networks and they point to our social model when talking about the attractiveness of France," he says.

Up-to-date statistics for unions across the national labor market were unavailable. But Martinez says in recent years, he's noticed CGT's membership declining, and labor sociologist Boisard believes the trend is occurring in other unions too.

Some workers don't see the advantages of joining a union: In France, the agreements they negotiate apply to all employees.

"We're no longer able to bring tens of thousands to the streets with a single call to strike," Martinez acknowledges.

He says the union needs to attract young people. To do this, they are adapting their strategy.

With its communist, anti-capitalist roots, the firebrand union has long focused on "the class struggle." But Martinez says they're now concentrating on individual job satisfaction.

"Young people don't feel like they have any room for creativity in big companies anymore," says Martinez. "They aren't able to do what they know how to do because everything is about profitability."

Martinez points to young nurses and doctors at a rural hospital he recently visited. He says they get the training they need, but now have to restrict their time to seven minutes per patient to cut costs.

Sociologist Boisard says it may be difficult for unions to attract young people because times have changed and unions are struggling to adapt.

"Young people today are much more engaged with the world and more mobile," he says. "They don't want to build careers only in France." Boisard says that makes it much less likely they'll mobilize for purely French national issues. "Because now the whole world is open to them."

Back at the startup hub, there's not a lot of talk about unions, but there does seem to be an appreciation for the kind of society French unions have helped build. Some of the foreign entrepreneurs speak enthusiastically about the quality of life in France, including the five weeks of paid vacation.

Niel says he is proud of the French social system, which unions helped build and defend.

"It's not a form of communism," he says. "When I'm sick, I don't wonder if I'm going to be taken care of or if I have the money to be treated. When I go to a French hospital, I know I'll get good care. No matter who I am."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.