AIDS began as a frightening medical mystery, with clustered outbreaks in California and New York City. Dr. Paul Volberding, who later helped San Francisco General Hospital open a dedicated AIDS ward, remembers seeing his first AIDS patient on July 1, 1981, although he didn't know it at the time.

"I had just finished my training as an oncologist, as a cancer specialist," Volberding says. On the first day of his new job at San Francisco General, during "rounds" when doctors visit patient rooms and discuss their cases, he saw a patient with Kaposi's sarcoma, which he would later learn was a symptom of AIDS.

Volberding was fascinated, because he had never seen that kind of cancer, and the patient was surprisingly young.

"It was very interesting cancer," he recalls. "And I looked in the books and it wasn't supposed to be in 22-year-olds at all."

Kaposi's sarcoma is unusually rare, especially in younger people. A cluster of cases in New York City and California was one of the first epidemiological signs, along with outbreaks of an unusual lung infection, that indicated the emergence in the U.S. of a new disease involving a compromised immune system.

Volberding was suddenly on the frontlines of AIDS, watching as medicine, public health, and sexual politics collided head on.

Volberding says those early, uncertain years stand in stark contrast to the recent outbreak of a novel coronavirus: "Today, we know exactly what COVID-19 is, right down to its gene sequencing. The virus is already being studied for possible clues to effective treatments."

But in other ways, there are similarities between the two emerging epidemics and lessons to be learned from the public health response to AIDS.

With AIDS, it took two years until the virus that causes it, HIV, was identified in May 1983. Until then, there was fear, sometimes bordering on hysteria, that the disease could easily be passed along through sneezing, coughing or close contact, just like the coronavirus is transmitted today.

"I remember it as there's this mystery disease and people are falling like flies. We have no idea why," says Roma Guy, who was working in those days as an organizer for lesbian and women's rights in San Francisco. She later became a city health commissioner. She describes the impact of AIDS on her city as profound:

"The public health system had to go through a whole transformation," she says.

Anxiety and uncertainty

This wasn't just a medical earthquake, it was social and cultural as well. And many people had the same anxious questions regarding AIDS as we feel now about the coronavirus: How many would become infected? How many would die? When would it end?

I remember that it felt threateningly close. I had moved to San Francisco in 1981, ready to start an exciting life in a big city. I was just out of college — and had recently come out of the closet as gay. The last thing I expected was to start hearing news reports of a new cancer afflicting "male homosexuals" being discussed on national broadcast television — and being attributed to their "lifestyle."

I was 23 and living in the city's Haight Ashbury neighborhood. I knew lots of people who were scared, myself included. I couldn't stop worrying: Did I have it? Could I get it? How could I avoid getting it? No one knew back then. I asked my doctor, who told me — incorrectly — that I wasn't "the kind of person" who was likely to get it. I didn't know what that meant. He told me not to worry, but I couldn't stop, so I attended support groups for people who weren't sick with AIDS, but who worried about becoming sick.

Fear and stigma toward AIDS patients

In 1982, Diane Jones, now Guy's wife, had just graduated from City College of San Francisco School of Nursing and went to work at San Francisco Gseneral Hospital. She ended up working on 5B, the world's first inpatient HIV unit, for 15 years. Fear was one of her most vivid memories from that time.

"I could come in at eleven o'clock at night and there would be patients with three meal trays stacked up outside the room because people were too afraid to go [into the hospital room to deliver it] and nobody was really giving any guidance," Jones recalls. "This issue of really not knowing for certain how it's transmitted is really different than the situation that we have right now with the coronavirus."

But what wasn't different, at least for one group, was access to testing. Jones says women were largely forgotten during the early days of AIDS. But many of them were lesbians who had been helping gay men have children by using the "turkey baster" method, as she called it. Those artificial insemination left them worried about becoming infected with the virus.

"They would have to beg over and over and over again to get a test after the test was discovered, or to be really examined and determined that they had AIDS. Why was that? Because they weren't perceived to be at risk," Jones says.

To help with the stigma, Jones says LGBT health care workers like herself felt a special obligation to come out publicly, as a sign of solidarity with AIDS patients.

"So I identified with them not so much as a patient, but as a community member. And I think that occurred over and over and over again," she says.

The 'San Francisco' model: grassroots public health

Dr. Mervyn Silverman was San Francisco's public health director at the time.

"I hate to say it, but we didn't know what we were doing back then in those early stages," he says now.

Silverman recalls that before AIDS, public health departments focused on more mundane tasks, such as restaurant inspections or testing and treating non-fatal sexually transmitted diseases such as gonorrhea.

But AIDS posed new challenges to public health models. As it became clearer that one way the disease was transmitted was through sexual contact, it also became evident that top-down messaging about prevention wouldn't work. Gay men who had recently fought — and who were still fighting — for civil rights and societal acceptance wouldn't welcome lectures about sexual behavior from straight outsiders. So the city started giving public health money directly to gay and lesbian community groups. Those peer-led groups took the lead on testing, counseling and home health care.

I can't remember us funding other things in those days like that," Silverman says, "But it made our life easier and it made what we did much more effective.

Volberding points to the fact that the disease struck primarily gay men at a time when they were flexing their political muscles with new-found visibility.

"In San Francisco, the fact that it was in the gay community allowed us more political support," he says, "and allowed us to to use and help develop some of the community resources that were so essential in responding to the epidemic."

That new model of working within and with the affected community was soon called "the San Francisco model." These days it's become routine for public health departments to partner with community-based organizations to do culturally competent health education and outreach.

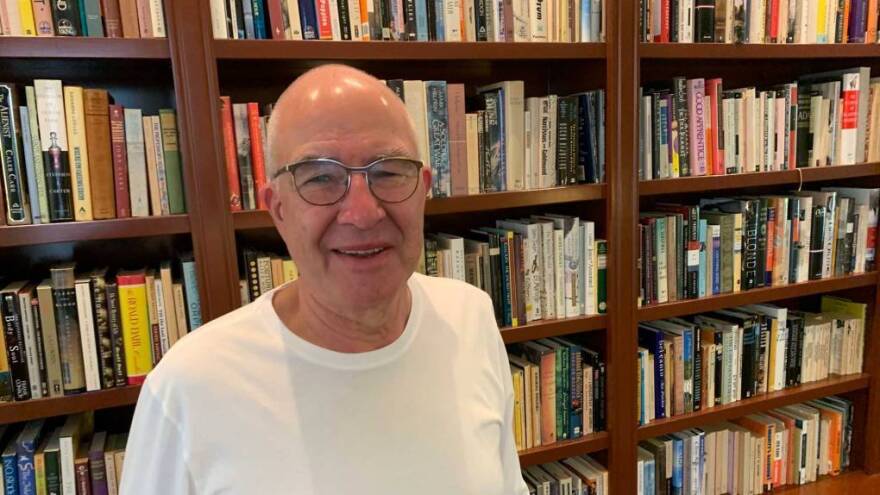

In addition to health workers, community organizing took place in cultural centers like Paul Boneberg's bookstore in San Francisco's Castro neighborhood. The store quickly found itself at the center of the AIDS epidemic and Boneberg co-founded a group called Mobilization Against AIDS to help answer questions and calm the nerves of the city's terrified gay community.

To spur federal response, activists organized

AIDS wasn't political at first, Boneberg recalls, but it became more so with the emergence of anti-gay rights ballot measures in states like Oregon and Colorado, and what many saw as the slowly-moving response from the federal government.

Boneberg says the focus of activists shifted towards speeding up the political and scientific response: "Meaning, let's try to get money for research. Let's try to get money to care for people," he says.

Boneberg believes the lesson of the AIDS epidemic is that there's no time to waste. "We need to all work on this together to make it happen and go faster," he says. "We always need to go faster, go faster, go faster. Get on it, move it forward. And those imperatives that come from the HIV/AIDS response are applicable right now."

With AIDS, the push for more government accountability and involvement eventually gave birth to activist groups like ACT UP, which began in 1987 in New York City.

Boneberg would like to think the history of AIDS will inform the current coronavirus experience. "We need to unify," he says, and "focus on testing and treatment for COVID-19 rather than dividing along political lines."

As with today's coronavirus pandemic, the emergence of AIDS led to concern and arguments over the shuttering of institutions and businesses, and the impact on local communities. One argument in San Francisco centered on the question of whether to close sex-friendly gay "bathhouses" and saunas, which many saw as symbols of gay liberation, but others viewed as places where the virus was easily spread.

Silverman, the city's health director at the time, initially saw the bathhouses as places where men could be educated about the risks of AIDS, but he eventually ordered them closed.

Collaboration proves key

For Silverman, that era was both exciting and deeply distressing. "It was fascinating, frustrating, depressing and exhilarating," he recalls, "Depressing because you looked at your friends and they were dying off, [and I was] going to a memorial service all the time. But also exhilarating, seeing the energy and the excitement in the way people were working together."

The coronavirus response in the U.S. today leaves plenty to criticize: not enough test kits, not enough masks and gloves for front-line health workers, and plenty of mixed messages from the federal government. Dr. Volberding says what they learned from AIDS decades ago about the crucial role of collaboration still applies today: "Some of the most important lessons were the connection between medicine — especially academic medicine — the public health system, the political system, the linkages that formed."

When the coronavirus came to the United States, San Francisco was one of the first cities to impose social distancing orders on March 17. Activist Roma Guy believes the city's experience with AIDS helped the current health director take control more quickly:

"He says 'There's a coronavirus. This is public health. I'm going to talk to the mayor,'" Guy says. "It's a whole different dynamic."

The experience of AIDS may also explain why the country is looking for leadership from people like Dr. Anthony Fauci, who has used his decades-long career at the National Institutes of Health to research HIV/AIDS and promote the research by others. Guy also points to the role of Nancy Pelosi, now speaker of the House of U.S. Representatives and a major player in pushing for coronavirus relief packages. Pelosi was first elected to Congress by San Franciscans in 1987, on a campaign promise to get additional AIDS funding.

"You have Fauci standing up there, you have Pelosi standing up there, who were at the epicenter of AIDS and have learned the essential lessons of what you do when you have a health challenge, how it becomes part of public health and then part of the governing structure," Guy says,

"That is an amazing lesson on the backs of people who died early from HIV."

Carrie Feibel contributed to this report.

Copyright 2020 KQED