Syria's foremost proponent of nonviolent protest says he's returning to Damascus this week and will keep delivering his long-standing message despite the country's worsening bloodshed.

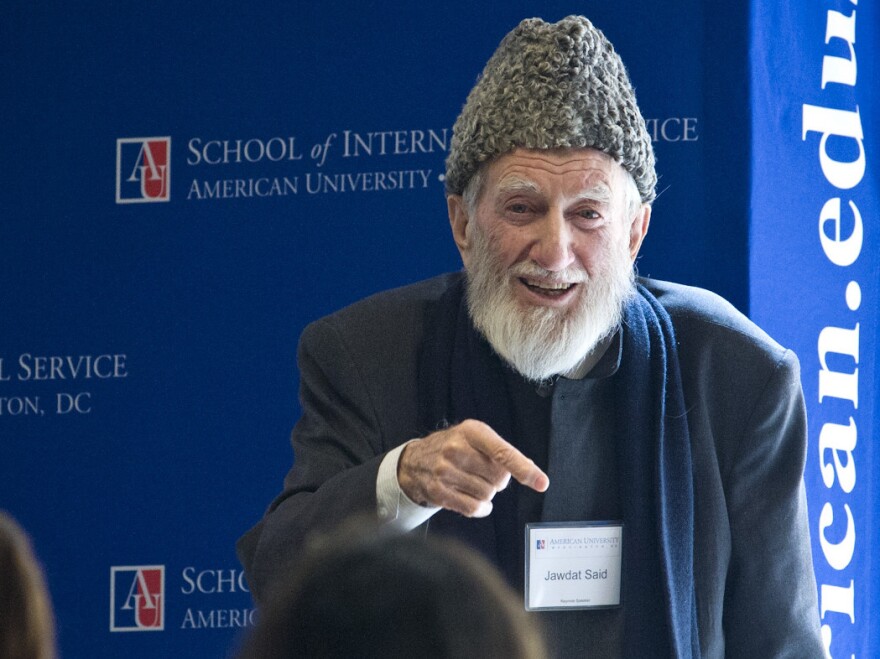

Sheik Jawdat Said is an 81-year-old Islamic scholar whose books and teachings helped inspire young Syrian activists to challenge the regime in peaceful protests last year.

He is little known in the West, but remains an influential teacher, according to activists in Damascus. Said returns to the Syrian capital at a critical time in the 15-month-old uprising, which seems to be descending into its most violent phase yet.

The United Nations Security Council unanimously condemned the Syrian government for an attack on the village of Houla. The deaths of more than 100 civilians there, including women and children, sparked international outrage. Many countries have expelled Syrian ambassadors. And Syrians who once believed in the power of peaceful rebellion are increasingly giving support to rebel soldiers and armed civilians.

Said has been on a six-month speaking tour in Canada and the U.S., which included a keynote address at American University in Washington, D.C., on nonviolence and the Arab Spring.

Asked if he was disappointed that the Syrian uprising was turning toward armed struggle, he said he will continue to condemn violence.

"Those who refuse to see still believe in the power of arms," he said by cellphone on his way to a speech at Ottawa University last week. "These people believe in the power of arms, not in the power of truth."

Those who refuse to see still believe in the power of arms. These people believe in the power of arms, not in the power of truth.

Often Jailed

Said has been jailed many time for his views, most recently in August 2000. He voted "no" in a referendum on Bashar Assad's candidacy for president. An official retrieved his ballot, crossed out the "no" and ticked the "yes" box. When Said complained, he was promptly arrested.

He played a key role in the early months of the uprising, explains Amr Azm, a Syrian-born professor of Middle East history at Shawnee State University in Ohio. Said had many young followers in the southern town of Dara'a, where the uprising began, and in Dariyah, a suburb close to Damascus.

Last year in Dariyah, activists handed out water and roses to the soldiers sent to suppress the protests.

A student of Said, Ghiyath Matar, 26, led the campaign. He was arrested in September 2011, and died in detention after being tortured, according to Human Rights Watch.

Said influenced the "peace wing," says Azm. "He's important because he's the last of what is holding that line together. Everyone else has moved to the military wing."

And, says Azm, his absence over the past six months has put him out of touch with the demands of "street," the young people who have lived through brutal military campaigns in cities across Syria.

"Peaceful protests are still an integral part of the movement," he says. But, he adds, " 'Long Live the Free Syrian Army,' is what people are chanting in a nonviolent protest."

No Fan Of Rebel Army

Said does not support the Free Syria Army, the loosely organized bands of rebel soldiers and civilians.

"We need to get rid of armies. Soldiers are rifles used by others," is his concise answer to a question about the growing popularity of the armed wing of the uprising.

Still, his return is widely anticipated by many activists who say there is a dire need for well-respected figures to play a visible role inside the country.

"We have already lost a generation of leaders from arrest and killings," says activist Karam Nachar. "We have younger activists that are brave but disorganized. They are lacking in vision."

Jawdat Said's pacifist vision has played a role in Syria's political opposition since 1966 when he published The Problem of Violence in the Islamic Action. His role as he returns to the Syrian capital is unclear.

"He is throwing himself into the lion's den. It is very brave," says Amr Azm. "This regime is in a bind. If they arrest him they are damned. If they don't arrest him they are damned."

The Risks Of Returning

Said acknowledged the risk. He's heard reports from members of his family in Damascus who say they can count the security men monitoring his street. His son, Bshir Said, 35, is also returning home with his father. Despite the risks, they must return home, he said.

"You stand for what you called for. You are one of those who started this, so running out of the country doesn't look right," the son said.

As for Said, a man who has been called the Syrian Gandhi, he's been jailed for his ideas before.

"I am over 80. I don't care what they do to me. I have always lived by these principles."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.