In Colorado, the presidential race is a statistical dead heat. The state went heavily for candidate Barack Obama in 2008 — but the president is now facing fierce headwinds.

Obama won last time by 9 points, an astounding margin in a state that hadn't gone Democratic since 1992. One Democratic strategist calls 2008 a one-time case of "irrational exuberance," especially among Colorado's large contingent of swing voters.

Not that all of those voters have abandoned Obama. Waiting in line for a rally with Vice President Joe Biden in the town of Greeley, registered Republican Amanda Lesinski says she doesn't understand why so many of her neighbors have soured on the administration.

"I'm kind of at wits' end with it because, right now, especially in Weld County, there's an oil boom kind of going on here in the Front Range of Colorado," she says, "and there are so many people working and [who] have better jobs than they had back in 2008."

But statewide, unemployment is a touch above the national rate, and Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney has earned new support from educated swing voters with his repeated references to his five-point economic plan and his promise of even more oil drilling.

The Democrats, meanwhile, are trying to solidify their base. In Greeley, Biden focused his charm on Hispanics.

"Over 25 percent of all public schoolchildren in K-12 are Hispanic, and the American people see what Barack and I see and what you see — they see nothing but promise in that," Biden said. "Nothing but promise."

"Nothing but promise" is exactly how Pauline Olvera would phrase it.

"He put all of our issues on the back burner," she says.

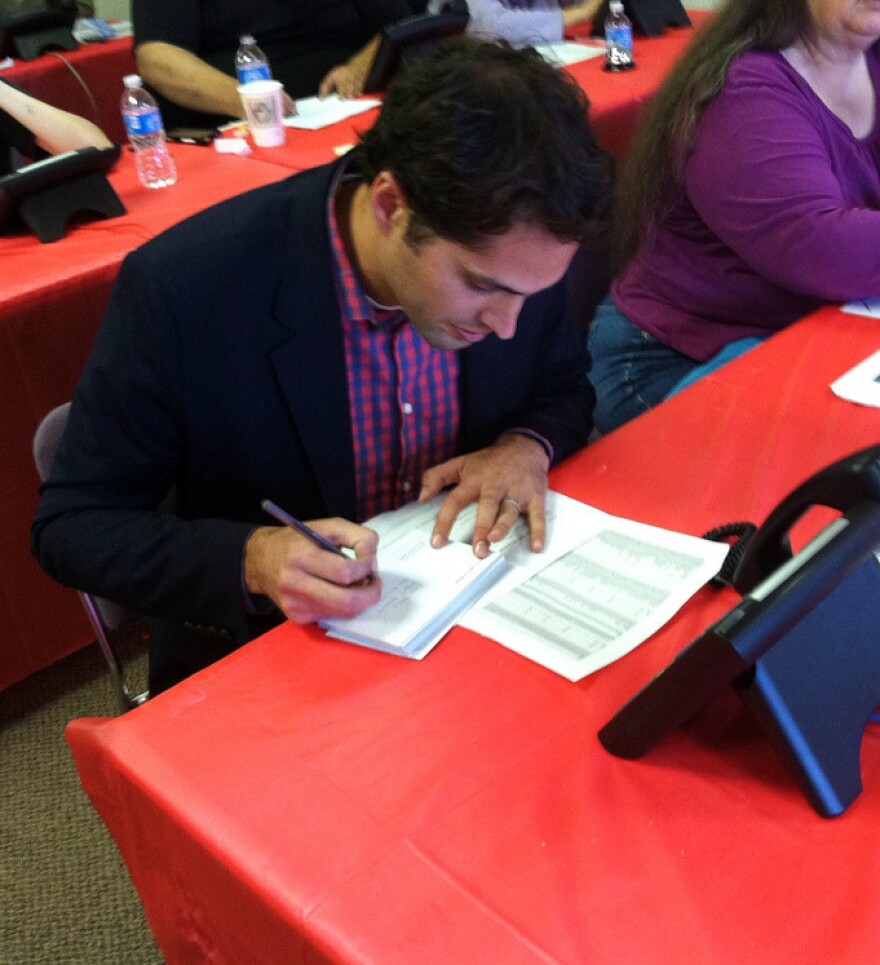

She says the Hispanic community is still waiting for the president to keep his promise to overhaul immigration laws. At a Romney campaign office in Aurora, she's addressing postcards to Hispanic voters, and the candidate's son Craig Romney has stopped by to help.

He writes the postcards in Spanish — he learned the language during his Mormon mission in Chile. How does he know the recipients read Spanish?

"I think they've done their research here," he says. "They've identified undecided Hispanic voters, and so that's how we're doing this."

This is just one form of the "microtargeting" in this campaign. Both sides are using increasingly sophisticated databases that contain a lot more detail than just party affiliation — and it's especially true online.

"When I'm on Facebook, my ads on the right-hand side are always like, 'Vote for Obama,' like 'Need to register to vote' — all that stuff," says J.J. Greenwood as she browses on her laptop at a Denver coffee shop.

Greenwood says it's pretty clear to her that both campaigns have already pegged her as an Obama supporter.

"I'm a young woman, I'm a lesbian, I like coffee shops," she says with a laugh.

So all she sees online is pro-Obama messages. In fact, because she doesn't watch much TV, she's hardly seen any Romney ads. And she says that's too bad.

"Because, personally, I think I should be able to see both sides. Like, I want to know what people think about Romney, and I want to know, like, what he's saying to people he thinks will vote for him," she says. "I think that's really interesting, and that's something I should know."

But because of microtargeting, a lot of Coloradans are hearing from just one side or the other. And despite the state's reputation for elections decided by independent swing voters, the race is starting to look more like what's happening nationwide — a struggle to bring out the party base.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.