In the Gwanak-gu neighborhood of Seoul, there is a box.

Attached to the side of a building, the box resembles a book drop at a public library, only larger, and when nights are cold, the interior is heated. The Korean lettering on its front represents a phoneticized rendering of the English words "baby box." It was installed by Pastor Lee Jon-rak to accept abandoned infants. When its door opens, an alarm sounds, alerting staff to the presence of a new orphan.

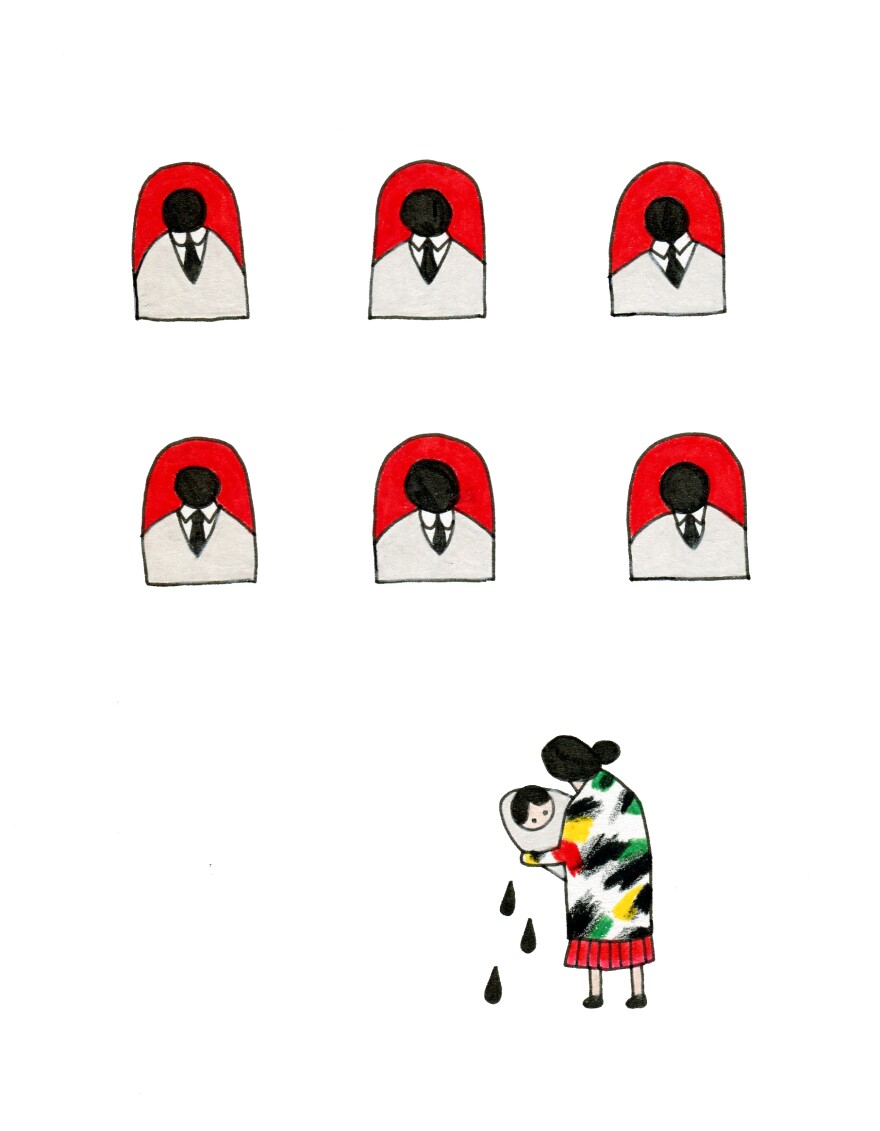

The box, and the anonymity it provides, has become a central symbol in a pitched debate over Korean adoption policy. Two years ago last month, South Korea's Special Adoption Law was amended to add accountability and oversight to the adoption process. The new law requires mothers to wait seven days before relinquishing a child, to get approval from a family court, and to register the birth with the government. The SAL also officially enshrines a new attitude toward adoption: "The Government shall endeavor to reduce the number of Korean children adopted abroad," the law states, "as part of its duties and responsibilities to protect children."

For the first time in Korean history, the country's adoption law has been re-written by some of the very people who have lived its consequences.

In the years after the Korean War, more than 160,000 Korean children — the population of a midsize American city — were sent to adoptive homes in the West. What began as a way to quietly remove mixed-race children who had been fathered by American servicemen soon gained momentum as children crowded the country's orphanages amid grinding postwar poverty. Between 1980 and 1989 alone, more than 65,000 Korean children were sent overseas.

For the first time in South Korean history, the country's adoption law has been rewritten by some of the very people who have lived its consequences. A law alone can't undo deeply held cultural beliefs, and even among adoptees, opinion is divided over how well the SAL's effects match its aims. The question of how to reckon with this fraught legacy remains unsettled and raw.

Korean Culture And Views

Family lineage is still a powerful ideal in South Korea. Even amid the breathtaking economic and technological advances of the past half-century, this vestige of foundational Confucian philosophy has remained.

Adoptees, having been cut loose from their bloodlines, still face considerable stigma.

Stephen Morrison lived on the streets of South Korea from ages 5 to 6. He then lived in an orphanage for eight years before finally being adopted. That adoption, to a family in Utah, was facilitated by Holt International — an agency that helped create the international adoption industry as it exists today.

"Adoption has been a tremendous blessing to me," Morrison says.

Now living in Los Angeles, Morrison is president of Mission to Promote Adoption in Korea (MPAK), a group that works to encourage adoption and the acceptance of adoptive families in Korea.

Prejudice against adopted children in Korea is not easily dislodged, in part because it is embedded in deep-seated cultural beliefs. Even those who are open to the idea of adopting may feel shame about their infertility and try to hide it. Morrison says that some Korean couples who choose to adopt will go as far as faking pregnancy in order to sell the narrative that the child is biologically their own. While a nine-month charade may seem extreme, the alternatives can be worse: Adoptive families sometimes find their openness and honesty met with derision.

Hollee McGinnis, a Ph.D. student whose research focuses on educational outcomes for orphaned Korean children who grow up in government-run institutions, says she has heard many stories of families who chose to be open about their adoptions at first, but eventually decided to conceal them. McGinnis, who is living in Seoul on a Fulbright scholarship, says the choice to conceal an adoption often coincides with a move to a new town, and that the adopted children themselves might drive this decision, hoping to escape ostracism that can turn severe. Adoptees often become the school wang-dda — the designated outcast and target of concerted bullying.

And these are the ones lucky enough to find an adoptive home within Korea. McGinnis says that according to her research, since 1950 just 11 percent of Korean children in need have been placed for domestic adoption. Thousands have landed in homes overseas, but the vast majority have been sent to institutions, out of sight and out of the collective Korean mind, where resources and opportunities are often scarce.

McGinnis says a lot of children end up at institutions because of abuse and neglect from their birth families. She says even the best of these facilities are often unable to provide the kind of one-on-one attention that can lead to better outcomes. By middle school, she says, many of these children will already be tracked for technical training instead of academics. This in turn equips them poorly, if at all, for the rigorous national exams — another Confucian holdover — that determine college admissions. And even those who get accepted to college find that while some government programs cover tuition, room and board is not included, effectively making a university education impossible.

In any event, kids age out at 18. Morrison says he knows all too well the kind of fate that can befall children who grow up in institutions, and the hardships that await them when they leave.

"With limited training and with limited financial support at the time of termination," Morrison says, "most of them wind up going to a factory to work if they can find opportunities, or wind up with meager-paying jobs." Moreover, he says, "Having an orphan background is a liability" — even beyond employment. "Many discriminate [against] such people," he adds, "and [do] not allow their sons or daughters to get married to them."

Unwed mothers, living outside the structure of patrilineal bloodlines, also face considerable stigma. The record of an unwanted child on a woman's family registry can bring unwanted scrutiny, and hurt employment and marriage prospects. Single women also face daunting economic realities. In an echo of the economic arguments made to impoverished women in the lean postwar years, women are often advised to give up their children, to give them the prospect of a better life, rather than raise them alone.

"Single moms really don't have a choice," McGinnis says. "There's tremendous pressure not to do it." This pressure has led many women — some alone, some with a partner at their side — to the baby box in Gwanak-gu.

Adoptees And Missing Identities/Histories

If adoption is a blessing, then for some, it is a mixed one at best.

Like many Korean adoptees, Deann Borshay Liem grew up feeling loved and accepted by her adoptive white family. She came to think of herself as an ordinary American girl who simply happened to have been born in South Korea. Then, while she was in college, repressed memories began to surface.

"I was walking down Telegraph Avenue in Berkeley," she recalls, "and I started having these flashbacks of the orphanage in Korea."

Sensing something was amiss, she asked her parents for her adoption papers. At first, her mother told her the papers had been misplaced in a recent move. An argument ensued, and an angry Liem got in her car to leave. But as she was backing out of the driveway, her mother appeared, holding a box of documents.

According to the papers in that box, Liem's Korean name was Cha Jung Hee. Her mother had died in childbirth, the records said, and her emotionally distraught father had killed himself soon after.

According to the papers in that box, Liem's Korean name was Cha Jung Hee. Her mother had died in childbirth, the records said, and her emotionally distraught father had killed himself soon after.

But Liem, still shaken by visions that kept returning to her, wrote to the orphanage. A few weeks later, she received a letter from her biological brother in Korea. The letter said her name was really Kang Ok Jin, that she was one of five children, and that her birth mother was still very much alive.

The father of the real Cha Jung Hee had not killed himself. In fact, he had come to the orphanage and taken her home. Not wanting to disappoint the Borshays, who had come to love Cha Jung Hee after exchanging letters with her over the course of two years, a social worker at the orphanage simply sent Kang Ok Jin in her place.

In her film First Person Plural, Liem tells the story of her adoption, her reunion with her Korean family and the sometimes painful conversations that followed. While Liem's story is unique, it shares an emotional topography with so many other stories of Korean adoptees: a sense of being caught between birth country and adopted country, and a sense of irretrievable loss. In a way, the film is the first major work of the Korean adoptee canon, not only because it articulates the cultural dysphoria, but because it also confronts the methods by which a steady supply of Korean children kept flowing overseas.

"Adoptees have told me that after watching First Person Plural, they felt it was OK to look at their adoption records with some scrutiny, and that they didn't have to accept everything," Liem says. "They could actually ask questions and challenge their own adoption narrative."

Director Tammy Chu did just that with her own personal documentary, Searching for Go-Hyang. ("Go-hyang" is Korean for "homeland.") Chu fled an abusive environment in her adoptive home before reconnecting with her birth family, discovering along the way that pieces of her own history had been withheld from her. Her follow-up, Resilience, follows an adoptee named Brent as he searches for, and is eventually reunited with, his birth mother, Myun-ja, who says she never wanted to give him up. The two try to make up for decades of lost time, across a chasm of language and cultural difference. In a follow-up to First Person Plural, Liem searches for the woman whose place she took on the plane to the U.S. (Along the way, she finally meets the social worker who made the substitution.)

While cases of switched identity like her own are rare, Liem says she has personally heard "many other stories of false or inaccurate information."

I feel like I was denied the chance to be a Korean person. ... If I hadn't been adopted, I would have been a productive person. I'd probably be married, and maybe have five kids. I may not have gone to college, but I would have been productive. And I wouldn't have spent so much time trying to come to terms with my identity.

For example, she says: "Adoption records might indicate that both parents are dead, but in fact the parents are alive. Or that the parents weren't married but in fact they were married, and there are siblings ... and so on. Unfortunately there aren't hard statistics about this kind of information."

MPAK's Stephen Morrison counters that falsification of records is not as common as some adoptees claim. "There are many adoptees that don't see this as an issue, as this probably allowed them to be adopted into loving homes," he says, including himself in this category. "I wouldn't accuse the agency for falsifying my records," he says. "I would just assume that the agencies either made up or guessed at missing information. For example, Holt assigned me my birth date. There is no falsifying involved here — just giving me an identity that I didn't have."

But for Liem, her records erased an identity that she did have.

"I feel like I was denied the chance to be a Korean person," she says. "If I hadn't been adopted, I would have been a productive person. I'd probably be married, and maybe have five kids. I may not have gone to college, but I would have been productive. And I wouldn't have spent so much time trying to come to terms with my identity."

Liem is currently at work on Geographies of Kinship: The Korean Adoption Story, a documentary that traces the wider history of the subject that has become her life's work.

"I was adopted when I was 8 years old," she says, "and am still recovering."

Adoptees Organizing

As the children of the Korean adoption boom came of age, they started finding each other.

Before she began her research, McGinnis spent years in Korean adoptee community-building. In 1996, she started a nonprofit organization in New York called Also-Known-As (AKA).

"I really wanted to create a space for adoptees to generate or create their own identities," she recalls. She had always known a few adoptees, but when she realized there were more than 160,000 like her, she went in search of Korean adoptees in America. She approached adoption agencies, who at first were reluctant to help, for fear of "angry adoptees." She approached Korean-American community groups, and adoptive parent groups, which also were hesitant at first. She set up a desk at the annual Asian Heritage Festival in New York City and approached anyone she could find — "feeling really rather ridiculous," she says, recalling a moment where she ran across the street to catch up with someone she'd been told might be an adoptee. "But that was what I had to do."

Slowly, the community took hold.

Similar groups proliferated, and they began to hear about each other, at first through word-of-mouth and email lists. Soon groups and the adoptees who comprised them began to connect on message boards, connecting their websites through "Web rings" — networks of websites in the pre-social-media era that linked to each other using a common icon to identify their membership. Eventually these more informal intersections led to larger meetups and regional conferences.

A diaspora was beginning to recognize itself as such.

By the late '90s, KAD connectivity was reaching a critical mass. Then came a watershed year: In 1999, the International Gathering of the First Generation of Korean Adoptees — more commonly known as the Gathering — took place in Washington, D.C.

"It felt like we finally came out as a community," McGinnis remembers. After years of word-of-mouth networking, long phone conversations, email chains and message-board threads, she says, "It was a chance to propel or coalesce what was going on independently, and to bridge with work in Europe."

For the first time, it seemed the spiral arms of the Korean adoptee galaxy had found a gravitational center.

Around the same time, Korean heritage camps for adoptees began to flourish around the U.S. — gaining in popularity thanks in part to shifting attitudes among parents who did not see assimilation as the only path, as many of their predecessors had.

Maggie Perscheid, an adoptive parent who continues to be active in adoptee-focused groups, says she initially saw international adoption as a "win-win-win" for everyone involved. But visiting Korea helped disabuse her of that notion.

"I learned firsthand the stories we adoptive parents tell ourselves about life being so much better in the U.S. for our kids not necessarily being the case," Perscheid says. "I experienced the pain of Korean mothers at the loss of their children on one of my first trips, and that had a huge impact on my ability to look at adoption as positively as I originally had." Later, she would find out that her daughter Mara had been placed from an intact family and had siblings, even though the Perscheids had been told her parents were unmarried. That, Perscheid says, "sealed my belief that adoption must be honest and transparent."

Perscheid is a board member of the Korean Adoptee and Adoptive Family Network, which held its first conference in a Los Angeles hotel in 1999. Around this time, increasing numbers of adoptees were returning to Korea and forming ad hoc communities. Some adoptees went for personal reasons, but stayed for political ones.

Artist kate hers RHEE, who grew up in Michigan, began a series of performances around Seoul aimed at alerting the public to the presence and situation of adoptees. One of these included handing out cards, inspired by Adrian Piper's "calling card" series, to Koreans who were unkind or not understanding of her apparently deficient Korean-ness. "Dear Friend," the card text begins, "Yes. I am speaking English. Your comments prompt me to tell you as you probably guessed I am a kyopo (overseas Korean). However, what you probably aren't aware of is I was adopted from Korea when I was young. Consequently my language skills aren't up to par." The cards were printed in both English and Korean.

(These days, RHEE wants to be clear that she does not refer to herself as a Korean adoptee. "I know it's an accepted term and also a specific politicized identity," she says, "but my thinking is — I'm no longer defined by that act that happened to me a long time ago.")

While RHEE's tactics were aimed at disruption and discomfort, other adoptees became overtly tactical. Alliances soon began to form among adoptees who returned to Korea as adults and were stirred to activism.

"The first turning point was reuniting with my birth family and finding out the truth behind my and my twin sister's adoption," filmmaker Tammy Chu says. From there, she says, working with fellow adoptees she had met in Korea, "We decided to create a space to start looking at intercountry adoption from a social and political perspective. And out of that, we began Adoptee Solidarity Korea [ASK], an organization that seeks to advocate, create awareness and support increased rights for birth families, single mothers and adoptees."

These more openly political tendencies ran counter to the goals of some other groups within the larger Korean adoptee community. When the 2004 Gathering convened in South Korea, the center was already showing signs that it could not hold.

A vocal contingent — some of whom viewed international adoption as an outgrowth of Western imperialism — pushed for more political action, while others insisted that providing a safe, nonjudgmental space for adoptees to network and learn from each other should remain a priority.

"At the time, the organizers [of the Gathering] were feeling that they were being attacked," McGinnis remembers.

After the official conference events ended, ASK held a meeting in the hotel. "It was supposed to be a kind of launch of an international political movement of sorts," recalls ASK representative Kim Stoker. "ASK has always firmly been a political organization in that we advocate for the human rights for adopted Koreans."

The tension at the 2004 Gathering caught some off guard, but as in any population of 160,000 or more, there are differences in experience, in background, in philosophy. And within those differences, adoptees may find themselves at different points along the path of engaging with their identity. For those just starting out, that may mean a feeling of instantaneous identification with other adoptees. For others, like RHEE, there is a desire to move away from being defined by adoption — and if being a Korean adoptee has stages, like grief, this is certainly one.

Still, Korean adoptee groups continued to hold local events, travel to conferences and organize homeland tours. The Gathering continued along its own path. Numerous related sites cropped up, including a variety of Facebook pages — some of them open, some of them closed to adoptees only. Meanwhile, the political arm of the movement soldiered on.

Jane Jeong Trenka reunited with her birth family after discovering her records had been falsified, and returned to Korea to be closer to them. She also began to agitate for changes to adoption policy, and in 2007, she joined with fellow activists to form Truth and Reconciliation for the Adoption Community of Korea. Within four years, TRACK would help bring Korean adoption law in line with its vision.

Effects Of The SAL

The baby box in Gwanak-gu is the only one of its kind in South Korea, and some view its monthly intake number as a grim barometer of Korea's ongoing struggle with how best to look after its unwanted children. Since the Special Adoption Law was revised, abandonment numbers at the baby box are up. That much is not in dispute, but just about everything else is.

To get a sense of how polarized the debate over the SAL continues to be, consider two different answers to the same question: "Now that two years have passed, what do you see as the main effects of the revised Special Adoption Law?"

Stephen Morrison of MPAK says the new law has "wreaked havoc" on adoption, and cites a long list of negative effects he attributes to the revision: reduction in the adoption rate; rise in abandonment; orphanages "overflowing with children"; increased illegal adoption; and increased numbers of women choosing to terminate their pregnancies through abortion.

Jane Jeong Trenka of TRACK says, "More unwed mothers are raising their kids, meaning there are fewer children available for adoption because the best choice has been made available to them."

The most controversial element of the new SAL is the requirement that mothers place their babies on their family registry. (The registry is an official family document suited to a collectivist society.) Even though the child's name will be removed from the birth mother's family registry once she is placed for adoption, Morrison says this element of the law in particular is helping drive a rise in abandonments.

"More children have been abandoned, especially at the baby box, because the law does not allow anonymous relinquishment of babies by the unwed mothers," he says. "Many have been abandoned in streets, restrooms, subways, trash bins, hospitals and unused buildings. In some cases, the children were murdered in motels, tried to flush down a toilet, thrown out the window to be killed. It is just awful." At the baby box alone, he says, 252 babies were abandoned in 2013.

Trenka doesn't deny that abandonments at the baby box have risen, but says the uptick doesn't coincide with the change in the law. For five of the six months immediately after the SAL revision passed, she says, abandonment numbers remained at or below pre-revision numbers. Instead, Trenka argues, the spike in abandonments coincides with a push to re-revise the law, led by a coalition of groups that included the three agencies permitted to perform international adoptions — Holt, SWS and Eastern — and Morrison's group, MPAK, which she describes as "pro-life." Trenka says the ensuing media coverage, which has focused heavily on the baby box, is a more likely cause than the law itself.

Furthermore, Trenka bristles at the conflation of abandonment and infanticide. "If the baby box is a true alternative to infanticide, we should see such killings decrease when the baby box is offered," she says. "Instead, we see that since the baby box was introduced, infanticides have stayed about the same." She says a mother abandoning a child and a mother murdering her child are driven to those decisions by very different circumstances.

Another widespread misconception, Trenka says, is that children cannot be adopted unless they are registered by their parents. But there is a provision in the SAL that allows the head of an adoption agency to create a family registry for a child who doesn't have one.

"If abandonments or illegal adoptions are going up it is because of misunderstanding of the SAL," Trenka says.

"I'm not 100 percent sure of the relationship between the law and abandonment," researcher McGinnis says. "Orphanage directors I've talked to say they have more babies being left at their doorstep. Whether it's a causal relationship — there's not enough evidence to say. But something is happening."

According to Trenka, the baby box itself "has only encouraged abandonment, posing as a legitimate form of child protection to women in crisis who need actual services."

Trenka and other advocates of the SAL revision argue that negative attitudes toward single motherhood are among the many facets of South Korean society that must change — along with the stigma faced by those who have been orphaned or adopted. By promoting policies that try to normalize adoption, including a May 11 National Adoption Day, and a provision that gives adopted children equal standing with biological children, advocates say the new law is moving Korea in the right direction.

McGinnis adds that the law plays well to shifting national attitudes. "Korean society wants to hear the TRACK and ASK narrative," she says, "that Korea can take care of their kids." She says it's a popular notion now, just as "back in the '90s and '80s, the other narrative — that we were ambassadors and bridges to the rest of the world — resonated." This shift in attitudes also correlates with other changes. Once a poor nation with more children than it could feed, South Korea now has the lowest birth rate in the world, and an average family size of 2.8 as of 2007 — down from an average of 5.5 in the mid-1960s.

There is disagreement over whether to celebrate this fact, but overseas adoptions dropped by more than 17 percent in the first year after the new SAL took effect in 2012. In any case, that shift had already been under way — domestic adoptions began to outpace international adoptions in 2007, the year TRACK was formed.

But while the SAL made adoption equal to blood in the eyes of the law, it is not necessarily so in the eyes of most Koreans.

"There are 17,000 children in 280 institutions throughout Korea," Morrison says. "They are not being adopted."

Even so, Morrison concedes that more unwed mothers are choosing to keep their children. "This is one good part of the SAL," he says. "However, I am not convinced that the unwed mothers are necessarily the best parents."

Additionally, the SAL makes the adoption process more time-consuming and complex, which Morrison says further discourages compliance: "This is another area where the Western influence has gone against the Korean culture of wanting [a] simple and quick solution."

Of course, one person's "simple and quick" is another person's "lacking accountability."

Asked if her life would be different had the law she helped change been in effect when she was a child, Trenka demurs. "Don't care to speculate," she says. "I have enough work dealing with the reality that already is."

Liem is more certain. "I do think my life would have been different," she says. "I think my family would have stayed together."

Liem's birth mother, a widow, was not well-educated and struggled to provide for her five children, who rotated in and out of orphanages as her finances ebbed and flowed. After a social worker asked her repeatedly if she wanted to give up one of her children for adoption, she finally relented. Had the current version of the SAL been in place, Liem's birth mother would have had legal recourse to reverse that decision.

"There's an emphasis on keeping families together in the new law," Liem says, "and that's a good thing."

It's a tension between, how much do you pull a culture and a society to change and how much do you let them evolve?

Whether the good of the law's intentions has been outweighed by its unintended consequences remains an open question. "It's a tension between, how much do you pull a culture and a society to change," McGinnis says, "and how much do you let them evolve?"

Steve Haruch is a writer and culture editor at the Nashville Scene. Adoption documents say his name was once "Oh Yong Chan." You can follow him on Twitter at @steveharuch.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.