Over the past few months, as the contentious ghost of Robert E. Lee galloped through the headlines, Southern food historian Michael W. Twitty's thoughts turned to the bittersweet connection his family shares with the Confederate general.

On April 9, 1865, Twitty's great-great grandfather, Elijah Mitchell, and his older brother, George, happened to be on a street in the village of Appomattox Court House, Va., when General Lee, in full dress uniform, exited the McLean House after surrendering to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. It didn't take long for the two teenage lads to grasp the import of that ceremonial tableau.

"At that moment, as the Confederacy's 150-year mourning period began," writes Twitty in his new book, The Cooking Gene, "my great-great grandfather and his brother counted themselves among the first black people to find out that the long nightmare of American slavery — nearly three centuries in the making — was over. Their slaveholder, Blake Mitchell, immediately declared them free — even as they still held his horse in place, waiting for whatever was to come next."

Twitty's prose movingly captures this momentous and profoundly personal moment and provides a glimpse of the scope and tone of his deeply researched, sometimes rambling, but altogether fascinating book that braids personal memoir, genealogy and culinary excavation to tell the story of a whole people through the lineage of their food.

Food is Twitty's flag. "They took our names, they took our gods, they took our religion but they didn't take our food," he says. His aim is twofold: to puzzle out "a recipe of who I am and where I came from," and, in doing so, to document how his captive ancestors radically enriched the diet of the antebellum South. They did this both through the produce — rice, okra, peanuts, cowpeas — that came with them on those slave ships from Africa, and through their skills in creating an "edible jazz" of barbecue, fried chicken, jambalaya, feijoada, spicy peanut stews, crispy okra, rice pudding and innumerable other dishes from their impoverished pantries. They were exemplars of farm-to-table and nose-to-tail cooking long before these hip terms were even coined.

In Twitty's percussive phrase, the "enslaved enslaved the palate of those who enslaved them."

Today, as the vexed debate over Confederate monuments consumes the country, Twitty's book makes for important reading. Food historians like Twitty, much like the groups rallying for and against the monuments, are enjoined in the battle of memory — in Twitty's case, the memory of who "owns" Southern food, and what role African Americans have in that commemoration. Twitty's frontline may be the kitchen rather than the traffic circle, but his subject is as viscerally intertwined with race as any Confederate monument.

"Our influence across the South," he writes, "conquered more territory than any Confederate army ever managed."

A ringing statement, for which unwitting support can be found from no less than the beau ideal of the Confederacy. Lee, who loved his black cook's fried chicken, once said that all he wanted was "a Virginia farm — no end of cream and fresh butter — and fried chicken. Not one fried chicken or two — but unlimited fried chicken." Moreover, during the Union blockade, when the South faced starvation, Lee praised the cowpea (also called black-eyed pea or cornfield pea) as "the only unfailing friend the Confederacy ever had." Ironically, it was the humble West African cowpea and the African peanut that kept Southerners fed when bread was scarce. "Living proof that African civilization was part and parcel of Southern existence," says Twitty. "They couldn't do it without us."

One of Twitty's projects is his "Southern Discomfort Tour" — a journey through the "forgotten little Africa" of the Old South. His approach is not that of a historian, but rather a "historical interpreter": He picks cotton, chops wood, works in rice fields and cooks for audiences in plantation kitchens while dressed in slave clothing to recreate what his ancestors had to endure.

On one such trip to Virginia, Twitty cooked at Lee's birth home, Stratford Hall, an imposing brick manor with a commanding view of the Potomac. He says:

"It's a big, old, cavernous kitchen. You could roast a whole ox in the fireplace if you wanted. The floor is all brick, so the cook could use the entire surface of the floor as a range. That brick floor will make your back ache and your feet feel like cement at the end of the day. Here I was, roasting chickens, making persimmon pudding, hot rolls, rabbit stew, oysters, and the light kept changing and getting darker and darker and the pots felt heavier and heavier. I'm in my interpreter's clothing — trousers, waistcoat, long shirt, kerchief — and caught between humidity and a December chill and it was the first time I really connected with the idea that not only was this not easy — it was tortuous."

And then there were the guests. A woman from the United Daughters of the Confederacy chose to pivot from an uncomfortable discussion on slavery to Stratford Hall's architectural details. The Daughters then went upstairs, and in Twitty's incredulous words, "wept over the crib of Robert E. Lee and prayed over it."

"At that moment," he says, "I had to run, I had to go, I felt I might have a one-man slave revolt."

On another occasion, at a South Carolina plantation, when an elderly German observed that America needed to deal with slavery like Germany had dealt with the Holocaust, the room of older white Southerners cleared out. "They couldn't take it," Twitty said in an interview. "They were there for us to be happy and cook and create wonderful smells in the kitchen. I'm not indicting them — they were older, probably the same age as the German man, but fed completely different messages of power, race, identity and truth."

Those messages also fueled the fusillade of tweets that Twitty directed at President Donald Trump in response to the latter's tweet that removing statues was like ripping apart the country's history and culture. But Twitty also cautions that while toppling statues may be exhilarating, it may also be a simplistic show of justice. "In my former town, Rockville, Maryland, they covered up the statue in honor of the Confederate solider the first time this debate had cultural currency," he says. "And guess what? Systemic racism still exists. Honestly, maybe we should reverse it. It feels like we are eating the icing before the cake. Fight and demolish systemic racism and micro-aggressions and then celebrate by removing symbols of the old guard."

Seeking "culinary justice" for African Americans is Twitty's contribution to this long fight. It's what propels his blog, Afroculinaria.com, what made him object to an article hailing a Southern white chef for "discovering" the African roots of Southern cuisine; and what prompted him to write an open letter to Georgia chef Paula Deen — he calls her "a cousin, not a combatant" — inviting her to discuss race over a shared meal at a plantation. "The South," he wrote, "isn't the birthplace or the natural home of America's racism. It has changed in many ways for the better, but now we have politicians and legislators trying to reverse the clock because they were horrified that a Black man got into the Oval Office. So we have a lot of work to do. I will sit anybody down at the same table, but they have to be willing to not go back to the patterns of the past. Sankofa — in the words of my Akan ancestors: take the good from the past and move forward." His letter went viral, but Deen didn't respond.

As someone who is black, gay and Jewish, Twitty is emblematic of everything neo-Nazis rail against. His calm retort is that "America is the only place on earth where I'm possible, and that is the dirty little secret behind these hate groups. They are here to take away the possibilities that America the Ideal represents." Undeterred by the Charlottesville riot, Twitty will soon be there, cooking at the Monticello kitchen where Thomas Jefferson's enslaved chef de cuisine James Hemings once turned out gourmet confections. Hemings' legacy is as important to him as that of Elijah Mitchell, his great-great grandfather.

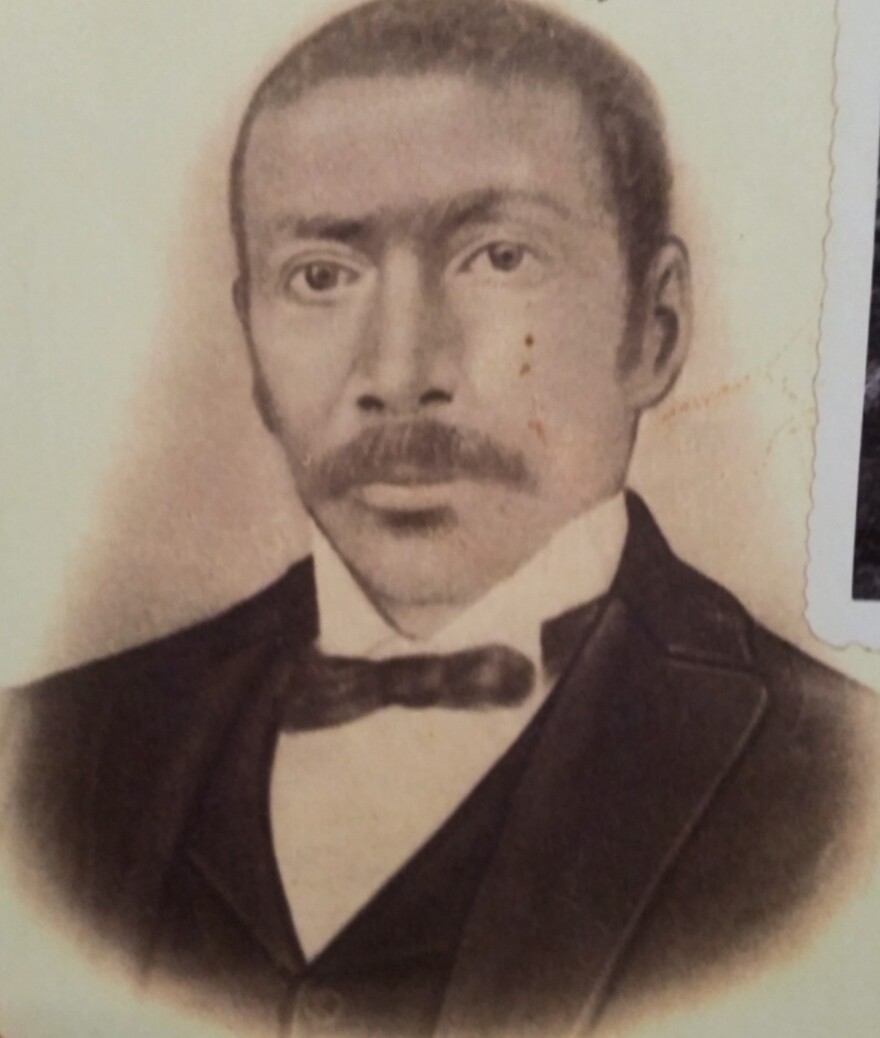

What happened to young Elijah? "He got land from the Mitchells after being a free hand for a while and a domestic," says Twitty. "He married twice and taught his wife and children to read and write. I'm really proud he valued education — as many Reconstruction-era black folk did — and he lived to a good old age and was a revered family man. He was handsome and smartly dressed in all the photographs of him. Not bad for a man who started life as a punkah puller (punkah is the Hindi word for fan), fanning white people in chains."

Elijah Mitchell died in 1923, during Jim Crow, when Confederate statues were going up across the South. He probably never imagined that one day his great-great grandson would recall his life story against the backdrop of those statues coming down.

Nina Martyris is a journalist based in Knoxville, Tenn.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.