European authorities are providing new details about a cloud of mysterious radioactive material that appeared over the continent last month.

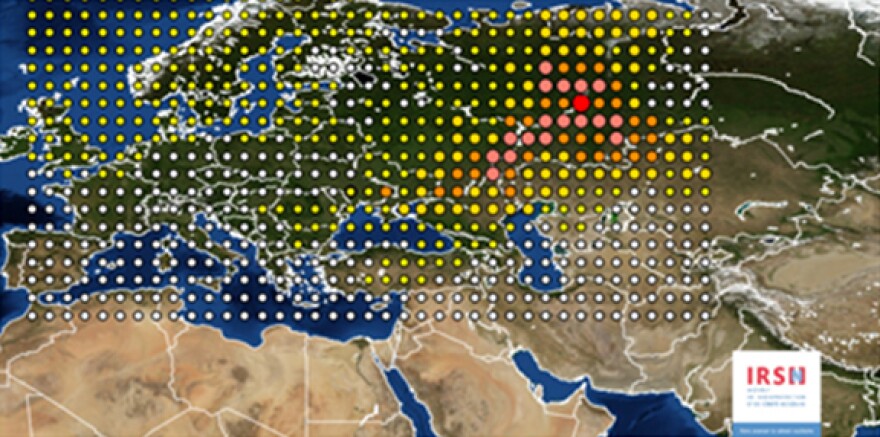

Monitors in Italy were among first to detect the radioactive isotope ruthenium-106 on Oct. 3, according to a fresh report by France's Radioprotection and Nuclear Safety Institute, known as IRSN. In total, 28 European countries saw the radioactive cloud, the report says.

The multinational Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organisation, which runs a network designed to monitor for nuclear weapons tests, also confirmed to NPR that it had detected the cloud.

Based on the detection from monitoring stations and meteorological data, the mysterious cloud — which has since dissipated — has been traced to somewhere along the Russia-Kazakhstan border, according to Jean-Christophe Gariel, director for health at the IRSN.

"It's somewhere in South Russia," he says, likely between the Volga River and the Ural Mountains.

Authorities say the amount of material seen in Europe was small. "It's a very low level of radioactivity and it poses no problems for health and the environment in Europe," Gariel says.

But modeling suggests that any people within a few kilometers of the release — wherever it occurred — would have needed to seek shelter to protect themselves from possible radiation exposure.

"If it would have happened in France, we would have taken measures to protect the population in a radius of a few kilometers," Gariel says. French authorities, he adds, will conduct random checks of foodstuffs from the region to check for possible contamination of agricultural products.

Ruthenium-106 is a radioactive isotope that is not found in nature. "It's an unusual isotope," says Anders Ringbom, the research director of the Swedish Defence Research Agency, which runs radioactive monitoring for that nation. "I don't think we have seen it since the Chernobyl accident."

The IRSN analysis suggests that the ruthenium did not come from a nuclear reactor accident. Instead, it most likely came from either the chemical reprocessing of old nuclear fuel or the production of isotopes used in medicine. Based on the size of the release, Gariel says, whatever happened had to have been accidental.

"It's not an authorized release, we are sure about that," he says.

A handful of Russian nuclear facilities are located roughly in the region where the ruthenium originated, including a large nuclear reprocessing plant known as the Mayak Production Association.

During the Cold War, the Mayak plant turned used nuclear fuel into material for nuclear weapons. The plant has been the site of numerous past accidents, including a 1957 explosion that rivaled the nuclear meltdowns at Fukushima and Chernobyl.

Gariel says that while Mayak is a possible source of the cloud, there simply aren't enough data to conclusively link it to the release of radioactive material. He also says he has spoken to Russian safety officials over the past few days and that while they do not dispute his analysis, they are unaware of any incidents in the region in the past few months.

NPR's Alina Selyukh contributed to this report.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.