Lora King was 7 years old when she saw the black and white video on television news, grainy footage of four police officers savagely beating a Black man.

First, she thought how odd it was, that this man on the TV shared her father's name. As she looked around at the faces of her family, she realized it was her dad. Then she thought, he can't survive this.

Lora King thought she was watching her father die.

When she saw him afterwards, she didn't recognize his face. It was so swollen and bruised. She was terrified, until the man smiled. It was her father's unmistakable smile.

Rodney King survived that beating, but his daughter says he carried its scars until he died in 2012. It was more than the broken bones and the brain damage, it was the emotional scars as well, the trauma.

When she thinks of her father now, she doesn't think of that video. She thinks of his smile. "His smile was electric to me," she says.

Lora King spent the weeks leading up to the 30th anniversary of the 1992 uprisings running from interview to interview, trying to honor her father's memory and support the foundation she runs that bears his name. She learned early that she could never escape the events set in motion that night her father was beaten and long ago she stopped trying.

"It's been my life since I was 7 years old," she says.

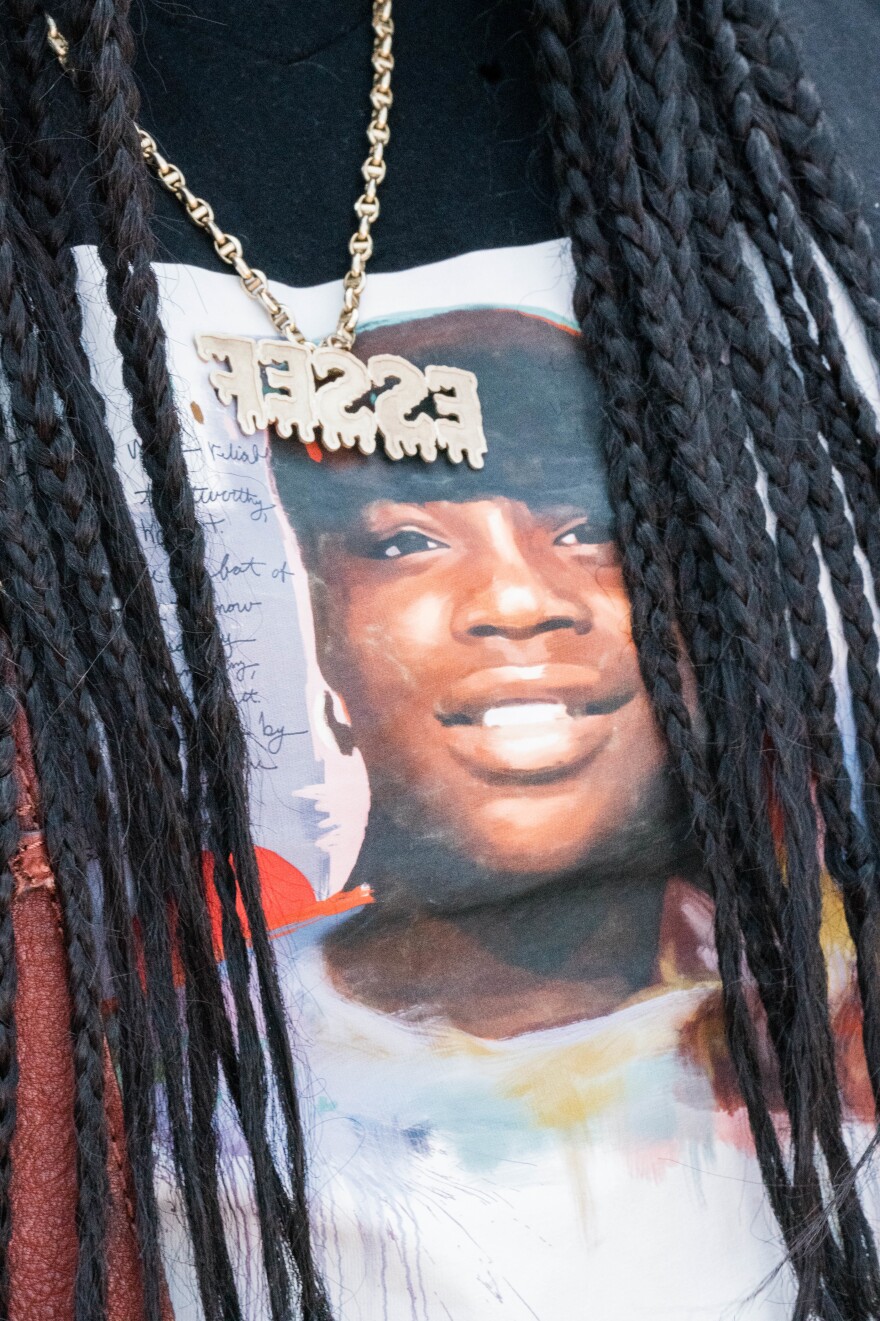

Thirteen days after police beat Rodney King, there was another grainy video tape capturing a horrific act of violence. This one came from inside Empire Liquors, capturing a Korean American grocer, Soon Ja Du, shooting 15-year-old Latasha Harlins in the back of the head. Du accused the teenager of stealing a bottle of orange juice. Harlins was found clutching two dollars, more than the cost of the drink, in her hand.

"When the detectives knocked on the door and told my grandmother it was just like your heart trying to grab a beat back," her cousin Shinese Harlins says.

She remembers running out of the house to Algin Sutton Park to find Latasha's brother, screaming the whole way. Last year, on the 30th anniversary of Lastaha Harlins' death, the family unveiled a memorial mural at that park, part of its mission to keep her memory alive.

"She was just a regular teenage girl," Harlins says. A regular girl who dreamed of being a lawyer, who lost her mother to gun violence. After Latasha Harlins' mother died, her grandmother took her and her younger siblings in, and Latasha helped raise them too. "She wanted to make sure her sister and brother were cool, that they had they head on strong," says Shinese Harlins.

"These cases really play out in the public in tandem with one another," says Brenda Stevenson, a UCLA professor who wrote a book about the Latasha Harlins' case, "almost as if they were parallel." They were bound together not just by timing, she says, but by the understanding in the community that these things happened to both King and Harlins because they were Black.

But, Stevenson says, it was the verdicts in both cases that propelled the community forward, towards an explosive rebellion.

In November 1991, Soon Ja Du was found guilty of voluntary manslaughter, but the judge in the case gave her no jail time. On April 22, 1992, an appeals court upheld that ruling.

Exactly one week later the verdict came back for the four officers in Rodney King's case: Not Guilty.

By then, Lora King was 8.

"We had just moved to the heart of South Central LA on 55th and Western," she says. She was walking to the liquor store with her sister and when they got there, it was on fire. They turned around and raced home.

"That's when I realized it was bigger than what I can imagine," she says.

Shinese Harlins says her mother put out a fire that someone started at Empire Liquors, the store owned by Soon Ja Du and her family.

"I remember her going to the motel to get buckets of water to put it out," Harlins says. She said, 'This ain't right.'"

Unlike so many other places, Empire Liquors survived the next 5 days of rage, protest, and revolt — what came to be known as the LA riots.

Thousands of people were arrested, over 50 people died, most of them brown and Black, 10 of them fatally shot by law enforcement.

UCLA history professor Robin D.G. Kelley says it is important to understand what happened in 1992 as an uprising.

"It was a rebellion against the beating of Rodney King captured on video," he says — but it was more than that. It was also an awakening of the "collective memory of all the other people who were beaten, but were never caught on camera."

Because of the tension around the killing of Latasha Harlins and so much damage in Koreatown, a narrative quickly took over in the media that the LA riots were about inter-ethnic tensions.

"And when that happens," Kelley says, "the question of white supremacy goes out the window."

"That narrative kind of deflected the public attention from police violence," says Kyeyoung Park, a professor of Anthropology and Asian American Studies at UCLA.

"It's not only African Americans and Korean Americans," Park says. "Because for instance, Korean Americans, they're not the richest people. It isn't like they have all the resources and power or, you know, privilege."

Park says we need to look beyond individuals, to systems of power — the criminal justice system, the financial system, policing, to understand the root causes of the uprisings.

Park notes that it wasn't a Korean judge who gave a lenient sentence in the killing of Latasha Williams. It wasn't a Korean jury that declared the four police officers not guilty in the beating of Rodney King. And it was banks, not Korean grocers, who denied loans to Black businesses so that most businesses in Black communities were owned by outsiders.

Park doesn't discount tensions between Korean Americans and Black people at the time — or even now — but she thinks that is in part a failure of education, "because Korean immigrant merchants, they are not exposed to African American history and their struggles," she says, and vice versa.

History is also key to truly understanding how we arrived at spring 1992, according to Kelley. "On the eve of the rebellion you have on the one hand, concentrated poverty, the lack of opportunities, plus the expansion of policing," he says.

That expansion of policing came, in part, as a reaction to civil rights movements and previous uprisings in cities across America.

"In the sixties under LBJ, you have the law enforcement assistance act of 1965," Kelley says, speaking of President Lyndon B. Johnson. "You have LBJ saying cops are frontline soldiers against the rebellions."

"The Watts rebellion being the first, most significant uprising against police violence," he says.

In response to Watts in 1965, the Los Angeles Police Department invented SWAT teams, which were first used on The Black Panther Party's Los Angeles headquarters.

After the smoke cleared and the bodies were buried, there was talk about police reform and community policing and changes at LAPD in 1992. Police Chief Daryl Gates, who invented SWAT, retired.

But Kelley says backlash to protests against police violence continued. "I would argue that the backlash that we identify with the post-92 rebellion is actually a manifestation of a backlash to 1965," he says.

Two years after the riots came the 1994 crime bill, which when paired with 1986's Anti-Drug Abuse Act, created a racist recipe for mass incarceration that targeted poor Black and brown Americans, according to Kelley.

"Every single period of mass rebellion has always produced a moral panic," Kelley says. "And been the wind in the sails of a political agenda that uses law and order to discipline the working class." That still holds true today, he says.

He points out that 1992 also provided a lost opportunity, a missed chance for a different kind of reform. "There was another plan for reconstruction after 92." It came out of the gang truce between Crips and Bloods, a truce made a day before the riots.

"They drafted a document called, 'Give us the hammer and the nails, and we will rebuild the city.'" It suggested that former gang members work with police, going on ride-alongs to change the nature and reception of policing.

The plan never came to pass.

"Rodney King is not the first Rodney King," says Lora King. Her father may have been the subject of the first viral video of police violence, but he was not the last. Cell phones opened the floodgates.

"The only difference between back then and now is hashtags," she says.

There has been some change, like a concerted effort to heal the wounds between the Black and Korean American community — that's work the Harlins family has been deeply involved in.

There's a movie coming out about Latasha Harlins soon. Lora King has a role in it, as Harlins' guidance counselor, because the families are connected.

"I have a few of those bonds," King says. "I have a bond with Eric Garner's daughter. I have a bond with Sandra Bland's sister. With George Floyd's sister," she pauses and shakes her head. "Oh man, I can go on and on."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.