So many people wanted him to speak, and he couldn't speak anymore.

After a dozen years at war, an estimated 2 million active-duty service members will have returned home by the end of 2013. Some reintegrate without much struggle, but for others it's not so easy. The psychological wounds of war can sometimes prove to be just as fatal as the physical ones.

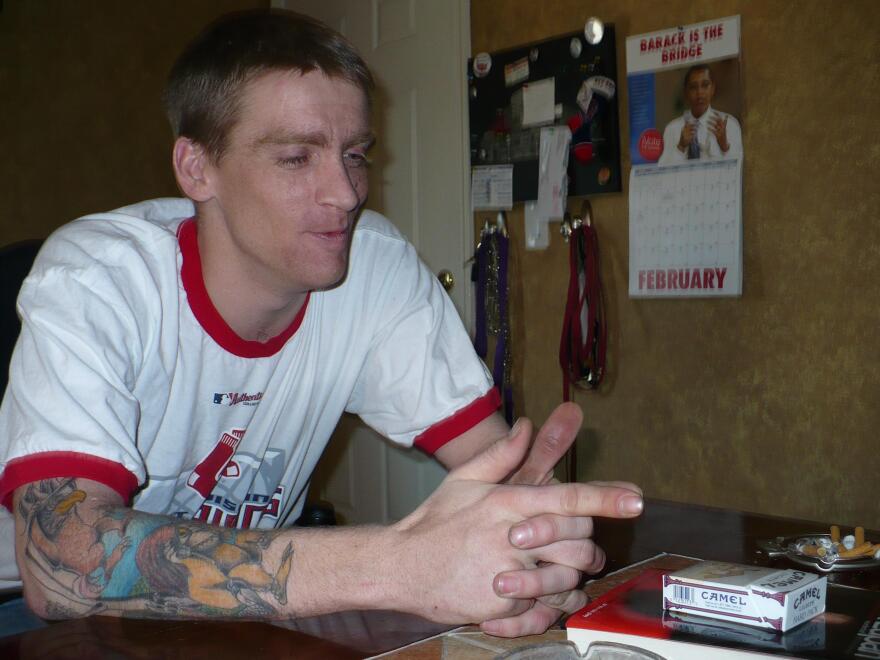

For injured veterans such as Tomas Young, life is a daily struggle. But this Iraq War veteran, who says his physical and emotional pain is unbearable, has decided to end his life.

At War

Before the attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, Young was an athletic, rambunctious 22-year-old. Now he's a man at the very end of his rope.

Young enlisted two days after the attacks. He wanted revenge against the Taliban in Afghanistan but was deployed instead to Iraq, a country that he believed had nothing to do with the Sept. 11 attacks.

Days later, a sniper's bullet left him paralyzed from the chest down, impotent and very angry. His terse, powerful way with words propelled him to the forefront of the anti-war movement.

The documentary Body of War follows Young's activism and physical struggles.

"I'm glad that it came out and people saw the reality of war," he says. "But now I can't even watch it, because it serves as a reminder of what I used to be able to do."

Young now spends much of his time lying flat on his back, smoking, in his dimly lit bedroom in Kansas City, Mo.

His life got progressively worse after returning home. A blood clot lodged in his lungs months after the film came out. That damaged his brain, twisted his hands and left his speech impaired. His mother, Cathy Smith, says it's been a long, hard fight.

"To be a paraplegic, deal with that, and then wake up and you're a quadriplegic and you can't use your voice, which is what you were learning to use," she says. "So many people wanted him to speak, and he couldn't speak anymore."

Love And Loss

Young spent months in rehab; last spring he married Claudia Cuellar, a Buddhist with a sunny disposition. Young is a devout atheist, but they both love music and literature, and share a keen understanding of the hardships of war.

"He is, of course, my No. 1 hero," she says. "Along with all ... Iraq, Afghanistan, Vietnam — all veterans."

They settled in for what they hoped would be a few good years together. But last summer, a horrible, new chronic pain hit Young. Doctors cut out his colon, hoping to ease his suffering. That worked for a while, but the pain came back.

"I decided that I was no longer going to watch myself deteriorate," he says.

In February, Young announced that he was going to remove his feeding tube and stop taking his medications — nearly 100 pills a day. Cuellar says she understands.

"His body's been mutilated. I mean, he had the injury, but then there's all the surgeries they've done on top of that," she says. "It feels dehumanizing."

In the nine years since Young was shot, his mother has had a lot of time to contemplate losing him.

"I've mourned the son that I sent to war, that didn't come home," she says. "I've mourned the grandchildren that I'll never have. The worst part about all of this for me is that none of this had to happen."

'He's Just Stopping'

Hearing of Young's plight, activist Ralph Nader suggested he write an open letter to former President George W. Bush and Dick Cheney — one final broadside against the war and its chief proponents.

"So I went along with that and wrote my letter, and I guess that thing's taken off like wildfire, too," he says.

Young's "Last Letter" from a dying veteran went viral. But he insists that, while the letter is political, his impending death is entirely personal.

"There are people who want to frame it as a political decision, or a political issue — that's their prerogative, yea for them," he says. "But I myself don't see it that way."

Young sees it as a solution to intractable suffering, but he knows that other veterans also suffer mightily and choose to live. He's also aware that many people abhor suicide; in fact, his mother is one of them.

"It's not a suicide. He's not killing himself, he's just stopping," his mother says.

The Patient Self-Determination Act of 1990 allows competent adults to refuse care, says Sandra Silva, director of graduate studies at the Center for Practical Bioethics in Kansas City, Mo.

"A health care provider can follow the instructions of a patient and not provide or withdraw medically administered nutrition and hydration," she says.

Young says he'll stop talking to the media on April 20, his wedding anniversary, and likely end his life a month or two thereafter.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.