There's been a lot of discussion about the name of a certain Washington football team — with lawsuits arguing that it is disparaging, and media outlets choosing not to use it in their content.

But while the debates around the language are raging, the logo — also a part of the trademark lawsuit — remains emblazoned on hats, T-shirts, and picnic blankets around the capital.

The logo has been the team's brand ambassador for a long time and this team isn't the only sports team to use Native American imagery. It's also not something that is exclusive to sports teams; caricatures and motifs depicting indigenous people have long been used to sell stuff — cigars for one, but also things like chewing gum and butter.

But there is another body of artwork out there — produced by Native American artists and entrepreneurs — that asserts ownership over the images associated with their culture. Their work counters the existing "non-Native" representations, questions these portrayals and provides new context.

'Apache' In A Transcultural Fabric

Jason Lujan lives in Brooklyn, pretty far from the small town in West Texas where he grew up. Lujan, who is Chiricahua, Apache and Mexican moved to New York after graduate school in Colorado in 2001. The move changed his outlook and his work.

"My entire approach is to present Native content, but in the way I see it existing in the world today — everything exists all at once, everything all at the same time," he says.

The word "Apache", for example, really fascinates Lujan. Through his art, Lujan shows how it's changed over time.

Growing up, "it meant who we were, but it meant who we were to outsiders....that's someone else's word to describe us," he says. But the images it invoked then aren't the same as now.

In Lujan's work, "Apache" exists as the helicopter, quite well-known around the world. Lujan juxtaposes that visual against newspapers in another language, in this case Chinese — quite literally, placing it in an international context.

In another piece, a part of his "Wild Places" series, he surrounds the helicopter with materials he found in his own neighborhood in Brooklyn such as packaging from a Muji store. At the bottom, there's a native pattern.

"It's an exercise in putting, forms and words and labels together with the 'Apache' element inserted in there at some point," he says. "It all needs to work in tandem with each other because that's how I see us operating in the world with equitable circumstances."

For Lujan, language is a way to approach another world view.

"When you say to someone — 'Native American' — there's kind of an ahistorical image that appears in their mind...someone on a horse or someone living in a very traditional way and that's not the entire story," he says. "My intent is to highlight a more contemporary context where everyone is connected."

Cowgirls And Indian Princesses

Sarah Sense was born in Sacramento. Her mother is Native American — Choctaw and Chitimacha — and her father is of European descent. Sense became acquainted with her Chitimacha family in college, when she worked on the reservation as a part of her scholarship program. During that time, she became curious about her connection with this community, about her own family and their heritage.

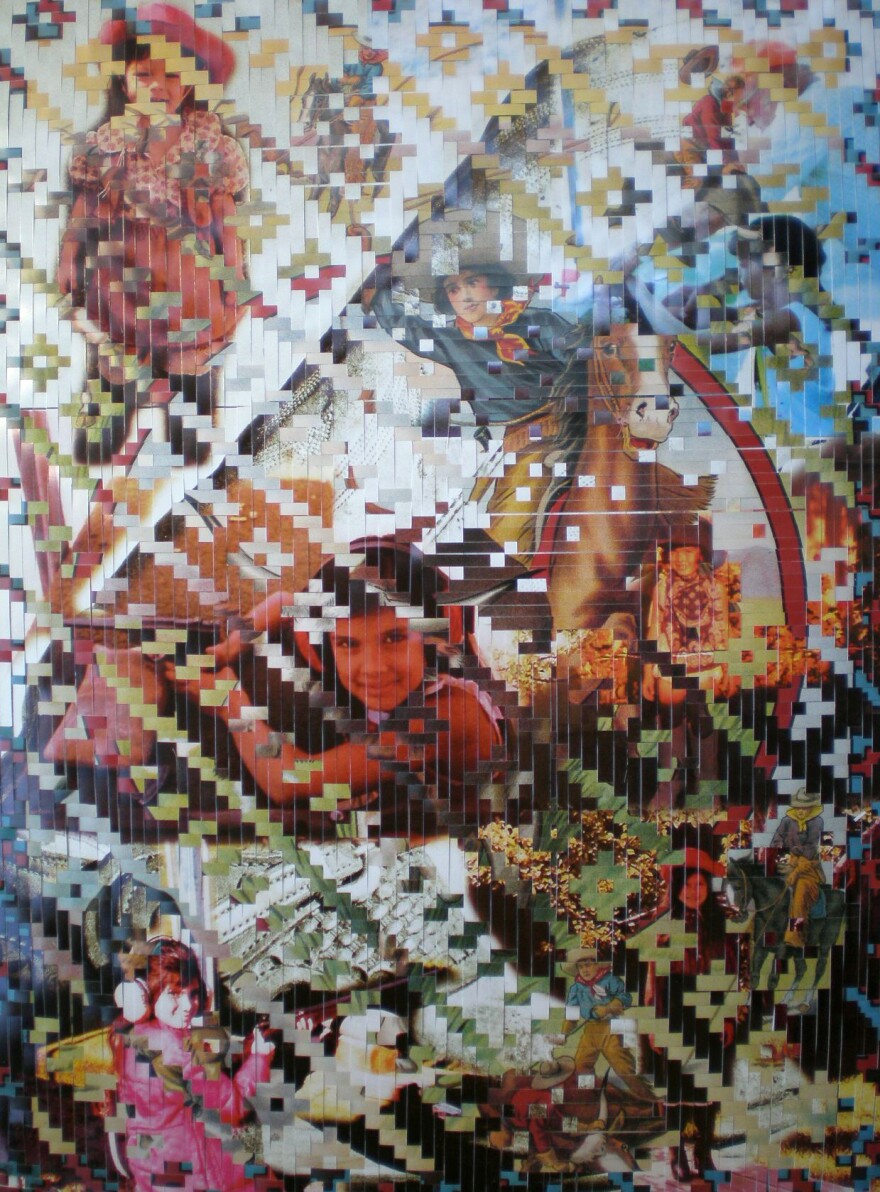

She was also fascinated by the traditional weaving practices — which she incorporated into her art at graduate school at Parsons. She uses photo paper as a sort of fabric, weaving it into depictions of the reservation landscape.

Sense continued using the technique in her next series — the "Hollywood" series.

"It had to do with politics of how women were portrayed, and also politics of how Native Americans were portrayed," she says. "I think for me, it was the best way to portray what it felt like... to embody the characters of those two personas — the cowgirl and the Indian princess."

The series is a melange of images from a couple of different sources. She uses old Hollywood posters she got from Sunset Strip and Burbank with the cowboy v. Indian tropes, images in antique stores, photos from Native American archives and combines them with family photos.

The piece above, for example, consists of pictures of Sense and her sister dressed up by their mother — who Sense says was very proud of their heritage.

She didn't want to personalize the experience, but humanize it by questioning, "The person in that photo — who's that person?"

Smiling Indians. Bad Indians.

Ryan Red Corn is a graphic artist and entrepreneur who grew up on the Osage reservation in Oklahoma. Once he got his degree in visual communications from the University of Kansas, he started a T-shirt business called "Demockratees." The T-shirts had Native messages and Indian-themed inside jokes.

But Red Corn soon expanded that to a branding business, helping Native American businesses tell their stories through the web.

Along the way, Red Corn came together with other Native American artists to start an comedy improv group called the 1491s. The group has released a stream of videos since 2009 in which they responded to the things they saw around them, Red Corn says.

The group's work is mostly satire — and like all satire, while some people read a lot into it, Red Corn says others don't get the point. That doesn't matter to the group, though.

"We reflect what we know and what we see," he says.

For the 1491s, the videos are one way to claim some artistic territory, and exert full control over it.

Red Corn has also dabbled in other visual media, making short films like Bad Indians and a film and portrait series of smiling Native people he sees around him. He produces images that don't adhere to the "noble savage romantic idea" that he sees in broader culture.

"What people attribute to my work is that I'm breaking new ground because I photograph Indian people smiling...but really, that should not be a radical notion," he says. "I don't have the luxury of the time to go and find that perfect indigenous specimen to photograph, I'm just photographing regular people."

Before (and sometimes now) Red Corn does a bit of what he calls "brandalism" — tearing down discriminatory advertising or corporations behind discriminatory symbols using the"brand equity that somebody has already poured into those symbols." Basically what that means is that he uses the symbols in the original advertising and subverts the message. But of late, Red Corn is trying to create original narratives instead of subverting old ones.

"If you want to tear down something old, you have to build something new," he paraphrases a Socrates quote he recently read.

In a media space crowded by messages, Red Corn wants to create a large enough body of work that "it can take up the maximum amount of bandwidth possible," he says.

"One of the things I try to do is put as much stuff into that pipeline...so that as a group, we're able to counteract those non-Native images that are representing us." he says.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.