Writer and illustrator Cece Bell has been creating children's books for over a decade, but in her latest, she finally turns to her own story — about growing up hearing-impaired, after meningitis left her "severely to profoundly deaf" at the age of 4.

The book, a mix of memoir, graphic novel and children's book, is called El Deafo. It's a funny, unsentimental tale that follows Cece from age 4 through elementary school, as she transforms from mild-mannered little girl into full-fledged superhero — the "El Deafo" of the title.

Bell sat down for an interview with NPR's Arun Rath, where the two talked about her story, her art style and more. Like her character in the book, Bell in can lip-read — as long as Rath's microphone was out of her line of sight. "You have a good voice too, and that helps," she told him with a laugh. "No mustaches or beards."

When asked why it took her so long to put her own story onto paper, Cece explained that she just wasn't ready yet.

"Even though in the book, it seems like at the end of the book that I'm totally cool with it, with having trouble hearing — it took me much, much longer in my life to get to that point," she says. "But suddenly I was ready so then I did it. And I'm kind of glad I waited, because I got a lot more experience as a storyteller with these other books, and I think that made me better ready to do it now."

Interview Highlights

About her hearing aid, the Phonic Ear, and the book's title El Deafo

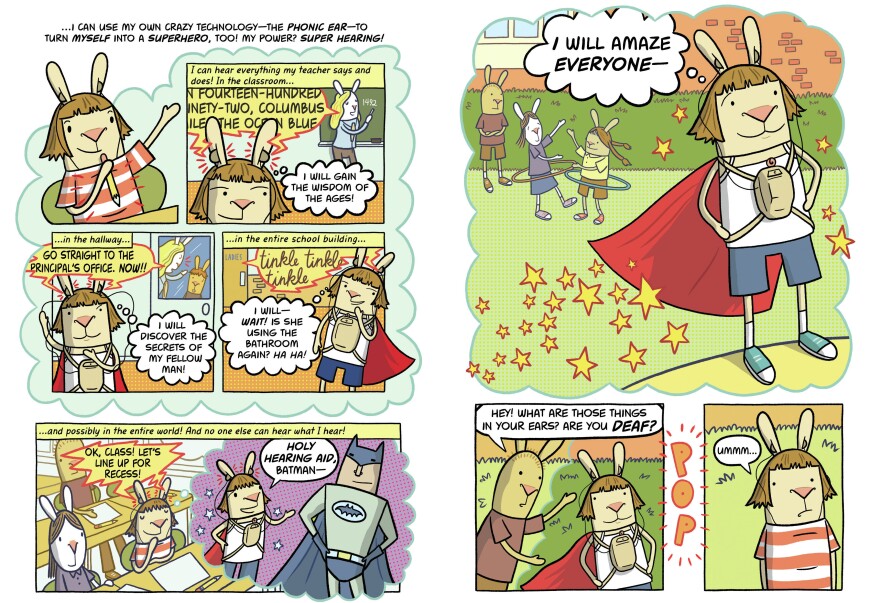

The Phonic Ear was a big bulky hearing aid. I wore it strapped onto my chest, and I had cords with earpieces that went up to my ears. This hearing aid worked with a teacher's microphone, and basically the microphone amplified my teacher's voice and made it really clear, really loud, just for me.

And soon after I got outfitted with it, I discovered that not only was I hearing her wherever she was in the classroom, but I could hear her wherever she was in the entire school building. So I had a lot of power, and it was awesome. ...

At home, [my deafness] was more of a disability. And in my mind it was [too], because I felt very embarrassed and self-conscious to be wearing all this equipment and to be different from everybody.

But because the Phonic Ear kind of gave me these superpowers — just like Bruce Wayne has to wear all that technology on his belt and turns into Batman — I had this awesome piece of technology on my chest that turned me in to El Deafo, this great superhero.

On using a graphic memoir to tell her story

This is the perfect medium for [this story] because of the speech balloon. For example — if as a lip-reader — if I'm wearing my hearing aids and I'm looking right at you speaking, I understand every word you say, because I've got some sound coming in and the visual clues from your lips. So in a graphic novel, that speech balloon would be understandable to everybody, what you were saying in that balloon.

But if I maybe had my hearing aids out and wasn't looking at you, your speech balloon would be empty, because I wouldn't know what you were saying, and I wouldn't hear what you were saying. And then if I had my hearing aids in, and I'm not looking at you — I can hear your voice because of my hearing aids, but it's all garbled, and so the speech in the speech balloon would be garbled.

It's just the perfect visual way to show all the ways a hard-of-hearing or a deaf person might or might not be hearing.

On the book's focus on regular elementary school life, not just deafness

I'm not a maudlin person. And one of my least favorite things are the movies that have some disabled person, and the violins come out, and it's all weepy, "Boohoo." That's not me. That's probably not most people with a disability.

And there's a lot of funny things that happen with equipment, with misunderstanding people. There's so much humor in it. And I wanted people to come away and think, 'Well, it's not all bad.'

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.