In the 19th century, French artists started getting creative with black materials— chalk, pastels, crayons and charcoal — some of them newly available. Now, a show called Noir at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles celebrates the dark.

"Black can be intense and dramatic," says Timothy Potts, director of the Getty. "I mean it's dark, it's the color of the night, of the unknown, of the scary."

Manet, Redon, Degas, Corot, Courbet, and lots of lesser-known painters began putting black on paper in lithographs, etchings, drawings. Of course it's not the first time black was used, but this was different because of Industrial Revolution technology and the times.

"Life was changing at a pace which it never had before," Potts explains. "And it wasn't all good — there was the poverty and the desperation of city life in a way that hadn't existed before."

"The air was terrible," adds Lee Hendrix, Noir's curator. "Urban violence was becoming a regular thing. The city — and especially the night city, and the city of Paris itself — began to take on life as a kind of demonic domain."

Artists reflected these shadowy changes. In 1827 Eugène Delacroix drew a demon — Goethe's devil Mephistopheles. The lithograph shows him flying over a dark city, the incarnation of evil with his claw-like nails and his grinning leer.

"I think they are plumbing the depths of the frightening, unimagined evil in ways that had not happened before in art," Hendrix says.

In Odilon Redon's 1880 charcoal Apparition, it's actually raining black, in long, dark, slanting lines. A dreamlike ghostly presence emerges from the dark. There's a bit of light around him — artists rubbed squished-up bread onto the paper, to lift away the powdery charcoal.

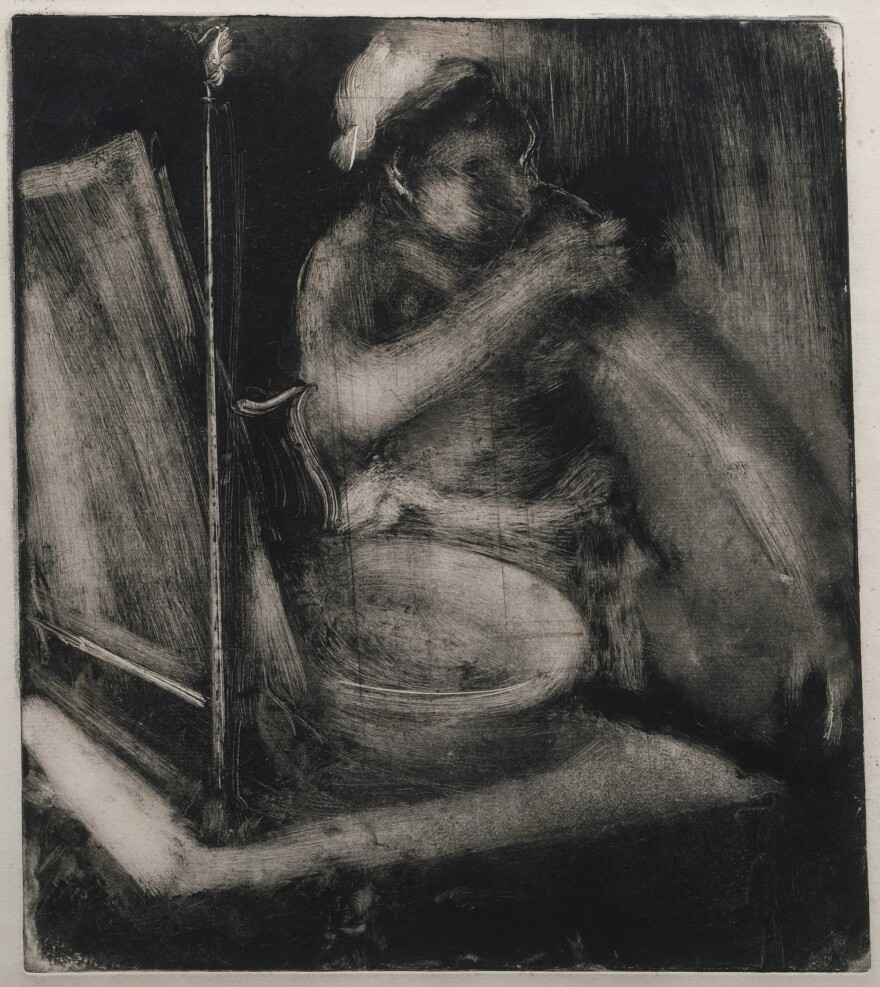

There's also an unusual Degas in the show: La Toilette is a monotype from 1885 which brought out the artist's dark side. Usually Degas used vivid colors in his paintings and pastels of women bathing. But here he puts black ink on a metal plate — and wipes it off, to create a bather's arms.

"[He's] wiping her arms as she's wiping her arms ... so the subject and the matter are married in that respect," says artist Alison Saar, who joined us at the Getty.

This Degas was a monotype — meaning there was only one copy of the work. But the Industrial Revolution brought ways to produce several copies of an artwork — mass-produced prints that were snapped up at art shows.

"These show were so well attended when you look at old engravings of them, they almost look like a department store," Hendrix says.

It was around this time that art got democratized — ordinary people could afford it. And that's something of a ray of sunshine piercing through the noir.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.