For years, federal programs for seniors and those that help kids have been on a collision course.

Now, given the automatic spending cuts taking place under sequestration, the moment for real competition may have arrived.

While Medicare and Social Security will come through the sequester mostly unscathed, a broad swath of programs targeted toward children — Head Start, education, nutrition assistance, child welfare — stand to lose hundreds of millions or even billions of dollars.

"There's a conflict between parts of the budget that go to younger people and that part that goes to older people," says Neil Howe, a demographer and consultant. "Up to this point, young people are on the losing side."

Groups that advocate for seniors say that this sort of "generational equity" argument is a misleading attempt to divide and conquer.

"It reinforces this notion that to take care of children, you have to undermine their grandparents in some way," says Eric Kingson, a social work professor at Syracuse University and founding co-chairman of Social Security Works. "It serves to drive wedges between groups that are very naturally joined at the hip."

But while it's true that cutting a dollar in Social Security won't send that dollar straight to the Head Start account, such programs are inevitably competing at a time of limited federal resources.

"The sequester again shows that as a country we're not willing to make an investment in our kids," says Mark Shriver, vice president of Save the Children.

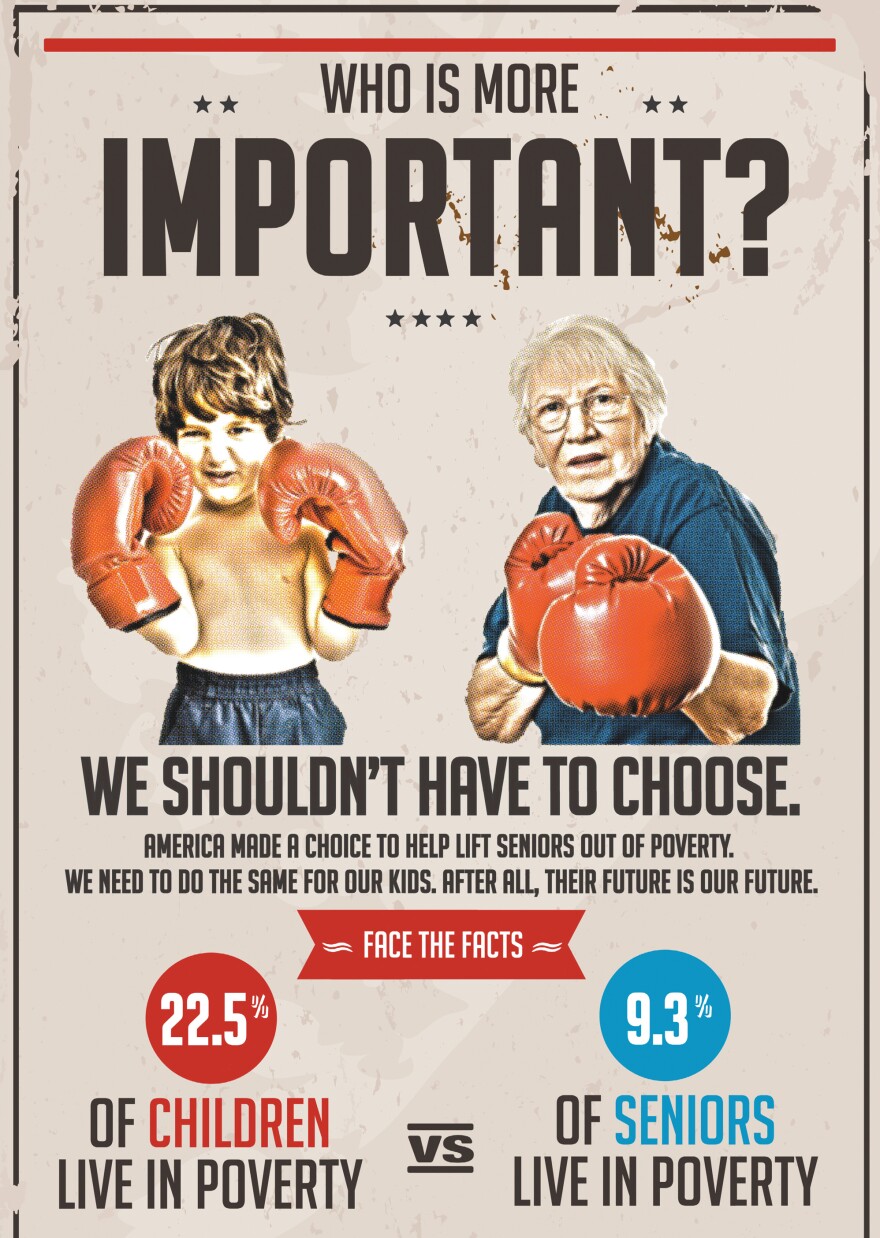

Federal spending on seniors already far outpaces that devoted to children. Last year, overall spending on children dropped for the first time in 30 years.

Given automatic increases baked into the entitlement programs, as well as increasing demands from an aging population, simple math dictates that spending for the elderly will grow only more generous under current law — and that threatens to crowd out spending on children, among other priorities.

"New revenue will be eaten up by entitlements," says Bruce Lesley, president of First Focus, a children's advocacy group. "In the long run, unless things change, kids will get almost nothing."

Not All Bad For Kids

It's a little misleading, though, to look only at federal dollars. Washington may spend more on seniors, but that's partly because many programs that aid the young are primarily funded at the state and local level.

"The federal government is in charge of the old people," says Dowell Myers, a demographer at the University of Southern California. "States do 90 percent of school funding."

Even at the federal level, while many programs that benefit children directly or indirectly are under the ax, others have been sheltered from the sequester — notably, food stamps, the earned-income tax credit and Medicaid.

"It could be much worse," says Julia Isaacs, a senior fellow at the Urban Institute. "The people who wrote the law exempted so many low-income programs, and children are, unfortunately, disproportionately low-income."

Speaking With Many Voices

Looking beyond the sequester, though, funding for kids' programs appears much more vulnerable than Social Security and Medicare.

Increased funding for entitlements is essentially on autopilot, while those that benefit children depend on members of Congress digging into the federal wallet on an annual basis.

Often, the kids lose out. While the very nature of entitlements means that they are universally available for seniors, millions of eligible kids are not able to take advantage of programs such as Head Start. Other programs, such as special education, are chronically underfunded.

Spending on children is also more diffuse. While seniors are highly vocal about Social Security and Medicare, advocates for children have to try to protect a long list of different spending categories — education, foster care, health and much more.

"The kid community is very segmented," says Lesley, the First Focus president. "There's no AARP, which says it has 50 million members, for kids."

Boomers And 'Parasites'

The idea that disparate funding on old and young could trigger generational warfare has sometimes seeped into the popular culture. Christopher Buckley's 2007 satirical novel, Boomsday, opens with a mob of young people rioting outside a Florida gated community "known to harbor early retiring boomers" to protest a Social Security payroll tax hike.

Economics reporter Jim Tankersley, now with The Washington Post, argued in an essay last fall at National Journal that the baby boomer generation has sucked a disproportionate share of resources out of the country, calling his own father "a parasite."

Such open resentment is comparatively rare, however.

"Most of us live in families and communities; we don't live in isolation," says Donna Butts, executive director of Generations United, which promotes intergenerational initiatives. "Young people don't want Social Security to be eliminated for the older people in their lives, and the old people don't want to see schools cut for the younger members of their family."

Picking Between Priorities

Kingson, the Social Security advocate, notes that even programs that appear designed strictly to help the elderly, such as Alzheimer's research, will end up paying greater dividends for those who are currently young.

"Old people have a stake in children's policies," he says. "You don't have to rob Peter Sr. to pay Peter Jr."

But while it's true that today's young people will eventually grow old themselves, government budgets are about the present. And those who are now old are better protected than children and youth.

Shriver, the Save the Children executive, says it's "fantastic" that federal entitlements have helped bring poverty rates down among seniors in recent decades. But he wishes similar action were taken to help kids.

"Kids don't have any political juice — they don't have PACs, they don't have AARP, and poor kids, in particular, their families don't make campaign contributions," Shriver says. "That's why we as a country have invested [more] in seniors."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.