There's a familiar name on the ballot in Louisiana this fall. Edwin Edwards — octogenarian, felon and former four-term governor of the state — is trying to make a political comeback. With his roguish Cajun charm, and a new 30-something wife and 1-year old son by his side, the Democrat is running for Congress in a heavily Republican district.

Can he still woo voters, or is it a foolish campaign dredging up bad memories of the ethical swamp of Louisiana politics?

Turning The Charm Up — Again

Edwards is 87, and he spent eight years in federal prison for corruption. But don't think for a second that age or the pen somehow softened his ability to work his audience — including an NPR reporter.

"People who listen to public radio don't vote for candidates like me," he says.

Sporting suspenders and a crisply pressed polo, the silver-haired Edwards holds court in his Baton Rouge campaign office, with a baby bouncer stowed in the corner.

"I'm of the people. I'm common. I'm ordinary," he says. "I don't speak good English, cher."

But Edwards is anything but ordinary. He's the last in a line of larger-than-life populist Democrats who once dominated Louisiana politics — think Huey Long.

Edwards was first elected to Congress 50 years ago and spent four terms as governor, spanning the '70s, '80s and '90s. He was known for walking a shaky ethical line and for his penchant for gambling and women.

"People talk about me. And out of that came things like 'silver zipper,' " he says. "And I like to say, 'Well, maybe so, but now it's rusty zipper.' "

Ever confident, Edwards figures he's been on the ballot 26 times and came out on top all but once. No reason to give up on politics now, he says.

"It's in my blood. Old doctors don't want to quit. Old farmers don't want to quit," he says. "We feel fulfilled doing what we think we were called to do. And my calling has been public life."

Stephanie Grace, a political columnist for Baton Rouge's daily newspaper The Advocate, agrees that politics is in Edwards' nature.

"Some people go to Florida. Some people fish. Some people volunteer. Edwin Edwards runs for office," she says, laughing. "He's so in his element and he hasn't lost a step."

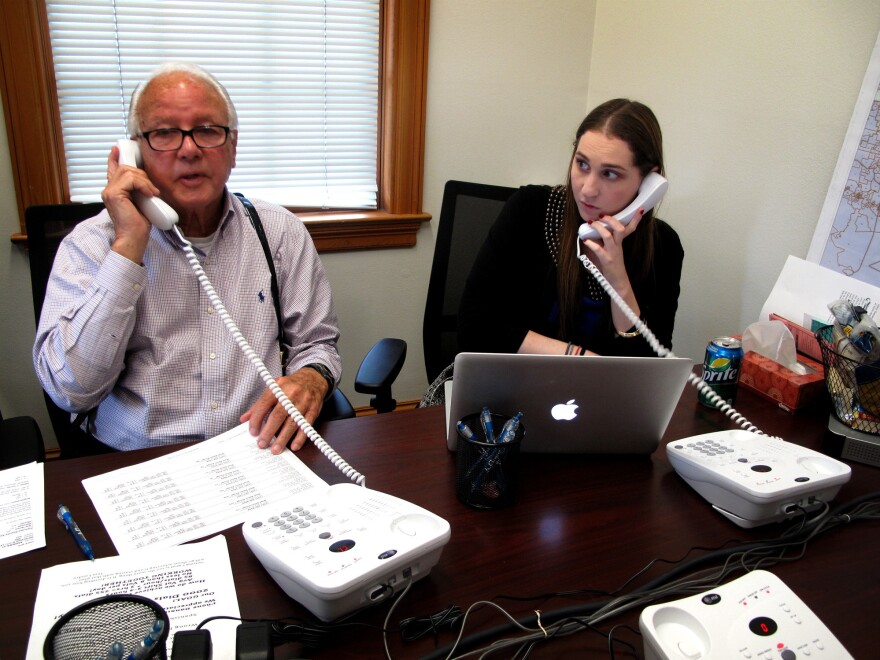

Even by phone, Edwards dials up the charm. "Maybe you recognize my Cajun accent," he says on one call. At the end, he hangs up with the promise of a vote.

The next call doesn't go quite so well.

"Put her down as doubtful. 'Cause she said, 'You already married to that good-looking blond girl, I don't have a chance. I'm looking for somebody else,' " Edwards says, as his campaign staff chuckles.

He and his third wife, Trina, met as prison pen pals while he served his time for extortion and rigging riverboat casino licenses. They were married when he got out in 2011. There was a short-lived and widely panned reality TV show, The Governor's Wife, featuring the couple and their infant son.

Then, when Republican Rep. Bill Cassidy announced he was running for the Senate, Edwards saw an opening — much to the surprise of pundits who thought he might not come out of prison alive, much less campaigning.

Old-Time Politics

Edwards' political tenacity is legendary. In the '80s, despite being dogged by federal prosecutors, he famously quipped the only way he'd get beaten was if he was caught with a "dead woman or a live boy."

"But even at that I don't know if I'd have lost had I been caught," he says.

In the '90s, he beat former Ku Klux Klan leader David Duke. The bumper stickers in that governor's race read: "Vote for the Crook. It's important."

Now, Edwards is one of 13 congressional candidates all facing off Nov. 4 in Louisiana's open primary system. If no one gets the majority, the top two candidates move on to a runoff in December. Most Democrats would never make the cut in this very conservative district centered on Baton Rouge.

In a speech to the Kiwanis Club in suburban Denham Springs, Edwards puts some distance between himself and the nation's top Democrat — while joking about his past.

"Now, look. I didn't vote for Obama when he ran. Where I was there were no voting machines," he says to laughter.

He's critical of the Affordable Care Act and supports the Keystone XL pipeline — issues the Republicans in this race are also talking about. He brushes off questions about seeking office in his 80s, saying he takes care of himself — doesn't smoke or drink. Gambling is his vice, he winks in characteristic style.

"You never count out old-time politics," says farmer and real estate agent Mickey McMorris, who's in Edwards' audience. A staunch Republican, McMorris says he'll vote for one of the GOP candidates. But he acknowledges Edwards has appeal even with conservatives.

"You know, I still hear people say he took care of the workingman," McMorris says. "And a lot of people haven't forgotten that."

That's the common theme from Edwards supporters — that he was a governor who looked out for folks.

In downtown Baton Rouge, retired state worker Daron Brown says he's glad to see Edwards back.

"He was a great governor one time, very positive for Louisiana," Brown says. "He made a mistake, you know. But who don't make mistakes? If God'll forgive him, I forgive him. So he got my vote."

A State With A Reputation For Rascals

Louisiana voters can indeed be very forgiving, says Albert Samuels, a political science professor at Southern University in Baton Rouge.

"We have a reputation in this state," he says. "It's still part of our culture, you know. We like our rascals."

Popularity may get Edwards into the runoff, Samuels says, but then he faces the reality of being a Democrat in state that's decidedly Republican.

"Louisiana is politically a very different place [than] when Edwards was in his heyday," Samuels says.

Longtime Democratic operative Bob Mann, now a communications professor at Louisiana State University, agrees. "The idea that any Democrat, much less a Democrat who spent eight years in prison, is gonna win this district is, I think, a pretty far-fetched notion," he says.

Mann says Edwards is selfishly seeking political redemption at the expense of Louisiana's political reputation.

"This adds to our indictment as a state that really isn't that concerned about the nature of our politics," Mann says. "We are more interested in being entertained than governed properly, perhaps."

For his part, Edwards makes no apologies for being that entertainer.

"Life is too precious and wonderful to be staid and colorless and without enthusiasm," he says. "I like doing things that make people happy."

And as he writes perhaps the final chapter of his political legacy, Edwards winds down his stump speech by telling audiences that he'd like their vote — but he'd rather have their respect.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.