Campaigning in Des Moines this week, former Pennsylvania Sen. Rick Santorum took pains to regularly remind voters that he won Iowa's 2012 caucuses.

"You did a great job in my opinion," he told a crowd of about two dozen. "You could have done a little better job in your math, but you did a great job otherwise."

Four years later, the Republican Party of Iowa is bringing in Microsoft to help with those math skills.

Motivated partially by the 2012 caucuses' reporting problems — it took about three weeks to figure out Santorum had topped former Massachusetts Gov. Mitt Romney in an especially tight contest — both Republicans and Democrats are updating their caucus night reporting process.

With something like the future of the free world, you want to be sure you got it right.

The state parties, which fund and operate the Feb. 1 caucuses, are turning to a solution that many use to get better organized: a smartphone app.

The app will record each precinct's tally, and send the results to party headquarters in Des Moines.

While the app itself is bare-bones and basic — it kind of looks like a calculator — it stands out in what will otherwise be a decidedly low-tech affair. Republicans often cast their ballots on slips of paper, and Democrats count their support for candidates by grouping together in corners at caucus sites.

Microsoft approached Iowa's Republican and Democratic parties with the app idea. The software giant developed the program at no cost as a showcase for its election-reporting technology.

Because the caucuses are party-run and aren't technically government elections, this kind of technology shift can happen very quickly, compared with the lengthy legislative and legal processes surrounding updates to voting methods.

Both parties were quick to sign up for the pitch. (Not all campaigns share the enthusiasm, though: The Bernie Sanders campaign will arm volunteers with its own in-house reporting app to independently keep tabs on results.)

Each precinct will designate one person who will download the app to his or her phone and record the evening's results. Those recording will need to be registered with either the Republican or Democratic Party beforehand, so they can be texted a two-step verification code on caucus night.

On the Republican side, volunteers will enter the precincts' total number of caucus-goers. If each candidate's vote totals don't equal that figure, an error message will pop up and the results won't be recorded. Democrats use a different, percentage-based counting method.

Microsoft says the parties will also be able to guard against reporting errors. They'll be able to set "thresholds for each precinct. We didn't expect a thousand people for this precinct, or we didn't expect two people in this precinct," said Stan Freck, senior director of campaign technology services.

Those settings, Republicans and Microsoft argue, will safeguard against the types of recording errors that sometimes plagued the old system: a simple automated telephone hotline, which volunteers would call to punch in their sites' totals.

That phone hotline was "liable to error — you don't get to confirm anything," said Ryan Frederick, Adair County's Republican chair. "It just goes off into the ether, and you watch the news to see if it was right."

Frederick will be tasked with reporting all the county's precinct totals on Feb. 1.

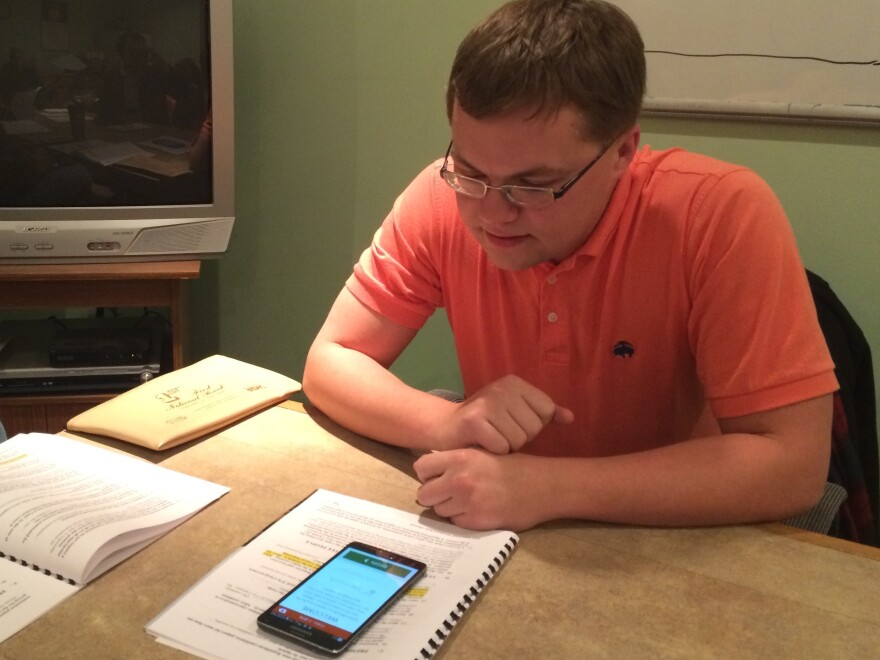

He seemed excited about the new app during a December training session.

"For those of you who remember the good old days, this is so much better," he told the handful of precinct volunteers who were sitting around an insurance office.

The caucus app makes complete sense to Frederick, who is in his 30s and uses his Android phone for just about everything. "If it isn't in this phone it doesn't exist," he said.

But not everyone feels that way.

Many caucus volunteers are less tech savvy, and Alex Latcham, who conducts caucus training sessions for the Republican Party, said he has spent a lot of training time just showing people how to download and install apps on their phones.

Microsoft's Freck said that has been the biggest hurdle during the run-up to the caucuses. "It's a fairly simple application," he said in the company's Washington, D.C., offices. "But as always, people are involved. ... There are over 1,800 precincts. So we're going to get precinct chairs and people who are involved that have all different levels of ... tech comfort."

That's a main reason why Microsoft and both parties are doing so many test runs before Feb. 1.

As Frederick put it as Adair County's training session wrapped up, "With something like the future of the free world, you want to be sure you got it right."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.