Judy Hoarfrost remembers the day she walked into China a half-century ago.

She was 15 and the youngest member of the U.S. pingpong team, which had been in Nagoya, Japan, competing in the World Championships. Two days before the tournament ended, Team China surprised the Americans with an invitation to come to their country and play some games.

It was the height of the Cold War, the U.S. did not recognize the People's Republic of China and had no relations with it, and Americans weren't allowed to travel there. But the team got speedy permission from the State Department. They flew to Hong Kong, and the next day they took a train to the border.

"That actually was a big moment for me, walking across the bridge," Hoarfrost recalled. "There was this music playing, and it was very, you know ... It was just very rousing. It was like being in a movie, really. It was just very dramatic."

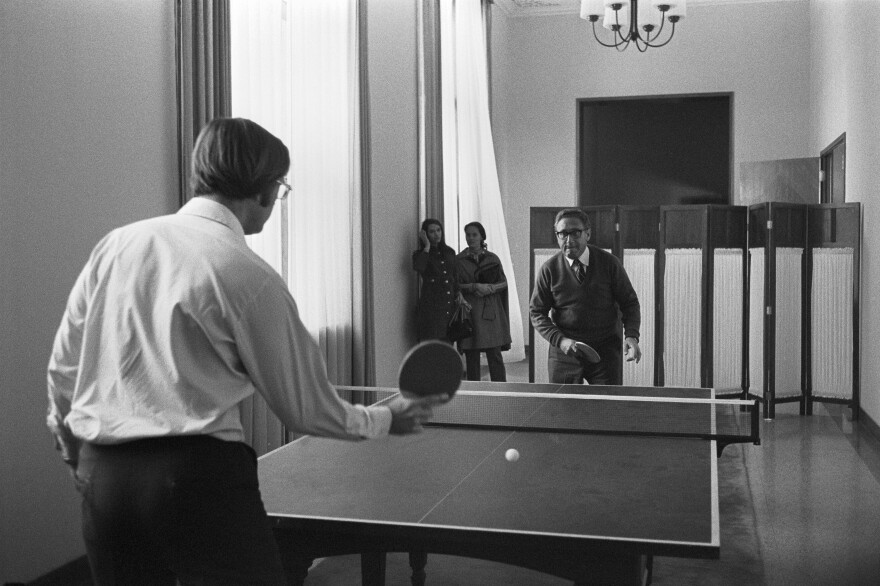

April 10 marks the 50th anniversary of that unlikely trip, an episode that's come to be known as pingpong diplomacy. Analysts say those pingpong games in China put the first crack in the ice between the two countries.

Within three months, President Richard Nixon would announce that he had been invited to visit China. By the start of 1972, Beijing would be admitted into the United Nations and installed on the Security Council. And by the end of the decade, the United States and China would establish formal diplomatic relations, paving the way for America's support of China's spectacular economic rise.

But today, with the balance of power in the Pacific shifting and U.S.-China relations at their worst in decades, analysts say the legacy of pingpong diplomacy faces stark challenges.

In 1971, the winds were blowing in the right direction.

Nixon was keen to connect with China, in part in the hope that it could help end the Vietnam War. China and the U.S. also shared a common foe in the Soviet Union.

Historians say Chinese leader Mao Zedong, and Premier Zhou Enlai, who drove rapprochement from the Chinese side, were acutely aware of the Soviet security threat. The two countries had experienced border clashes in 1969. Mao and Zhou reckoned that isolation and perpetual estrangement from the United States were ultimately bad for China.

But Chinese propaganda had painted America as an enemy for decades.

"When Mao wanted to improve relations with the United States he needed to prepare the Chinese public psychologically and politically," said Yafeng Xia, a senior professor of history at Long Island University and an expert on Cold War relations between China and the United States.

Inviting the U.S. pingpong team to China, he said, "was a good public show of friendship." It didn't hurt that the Chinese were far superior pingpong players. When the Americans were in town, they intentionally threw a few games — in the service of friendship.

But today, the political winds have shifted — in both countries.

"You could say that 1971 was the Book of Genesis for the chapter which we've now conclusively come to an end in, namely that somehow we would find a way to get along and work things out," said Orville Schell, Arthur Ross Director of the Center on U.S.-China Relations at the Asia Society.

Bipartisan support in the United States for a tougher posture toward China has grown as Beijing's economic and military power have expanded. Trump administration officials jettisoned the long-standing policy of engagement, labeling it a failure, and set out to decouple the world's two biggest economies.

The Biden administration, so far, appears to be taking a similar tack.

For China's part, the differences between 1971 and today are stark. China's GDP per capita has risen more than 80-fold. It's military has modernized rapidly, and can project power in ways that were unthinkable 50 years ago.

Schell said that's emboldened China's current leader, Xi Jinping.

"Xi Jinping is very unrepentant and presently I think [his] motive is not to show any deference to the West, not to evince any need to come together or compromise," Schell said.

It's hard to imagine exactly how a breakthrough like pingpong diplomacy would happen today, he added.

"In many ways, it's more intractable, I think, at this point, because China is growing in strength, growing in ... whether it's confidence or arrogance, it's hard to say," he said.

Talk of a possible boycott of the 2022 Winter Olympics in China over human rights is on the rise.

And that's something that Connie Sweeris, who was a player on the trip to China in 1971, says is the opposite of what's needed.

"You're stopping the exchange of normal people and athletes getting together and that's where I feel barriers get broken down," she said.

Judy Hoarfrost agrees.

"The more we have of those kind of healthy exchanges, the better off we are up the chain when we try to work on bigger problems," she said.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.