In 2003, France got a glimpse of what the future may hold. A summer heat wave broke all temperature records, straining the country's medical and energy resources. But a future of warmer summers could bring unexpected pleasures — including wine.

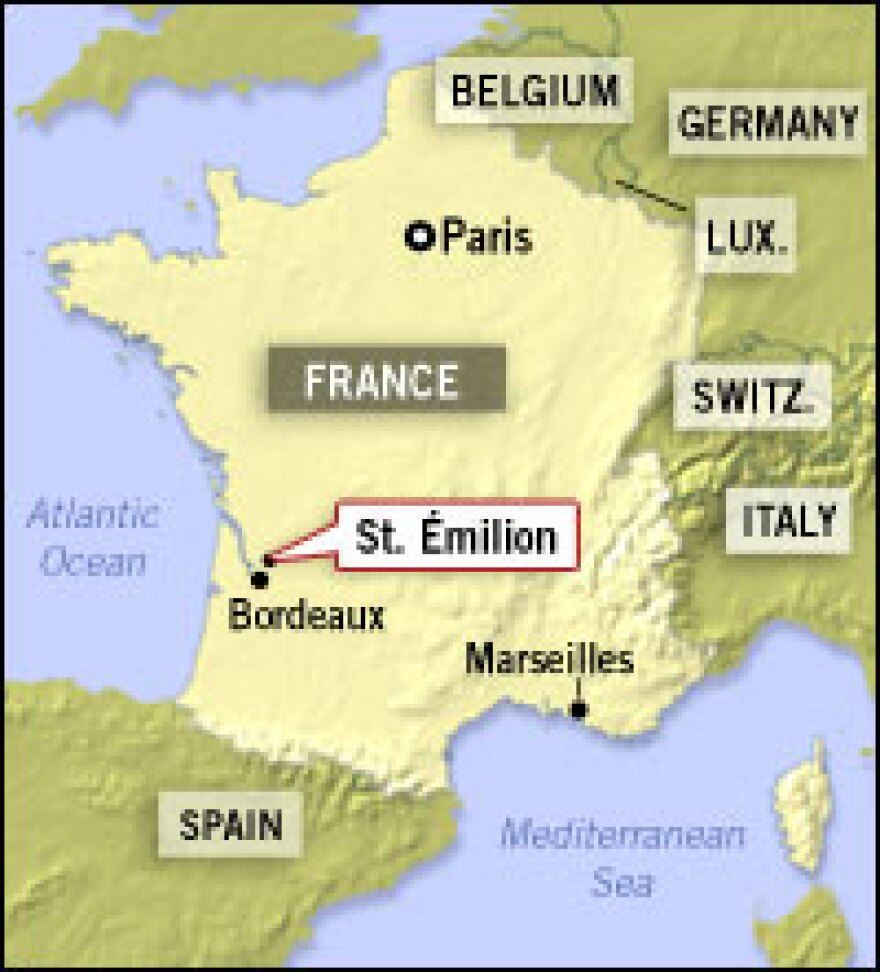

The town of St. Emilion lies in heart of a France's famous Bordeaux wine region. Beside just about every road there are row upon row of exquisitely manicured grapevines. Francois Despagne, the winemaker at Chateau Grand Corbin Despagne, explains that it is impossible to produce good wine without good grapes. And he should know. Despagne's family has been living in this part of the Bordeaux wine region since the 16th century. Today, he has 200,000 plants on 53 different plots.

If you follow strict rules about how you grow your grapes — where you grow them, and what type you grow — you can qualify for the St. Emilion appellation. The better vineyards qualify for St. Emilion Grand Cru, and the best are Premier St. Emilion Grand Cru Classe.

Despagne says that French wines are so special because French winemakers pay almost religious attention to something the French call terroir.

"Terroir is weather and the soil," he explains. "Many people say it is the soil. No. It is the combination of the weather and the soil."

The soil in Bordeaux is a mix of gravelly dirt and clay, perfect for grapevine growth. The weather is good, too. There's not too much rain, and enough summer sun for the grapes to mature. But the weather varies considerably from year to year, and this affects the vintage.

Despagne says he had good vintages in 1988, 1989 and 1990, but each year was very different. "It is like three children," he says. "They are your children, but they are not the same."

Profiting from Warmer Summers

Something else is happening in addition to the annual variation. Harvests have been coming earlier — and grapes have had more sugar — because on average summers have been getting warmer. At least in the short run this is a good thing for Bordeaux, because a warm, dry August is a good thing for wine.

These changes are welcomed at Chateau Ausone, a premier Grand Cru Classe winery. The Ausone vineyards are just outside the walls of the medieval city, below the Romanesque church. They're on a southeast facing hill, so the grapes are bathed in the warm morning sun. The 2005 vintage hasn't appeared in stores yet, but if you want to buy the rights to a bottle when it does come out, it will set you back nearly $1,800. That's for one bottle.

And global warming could send the prices even higher, according to Alain Vauthier, the owner of Chateau Ausone. "I very sincerely think that right now global warming is very favorable," he says. "We're getting more and more great vintages. We have very sweet grapes like those that we want for great years such as '47, '61, '82." And he doesn't seem concerned about the climate getting too hot.

"In 30 or 50 years, I don't know what the climate will be," Vauthier says, "But we'll see. Actually, I won't see, because I'm too old."

Growing Practices Change

Most winemakers won't be getting thousands of dollars for their 2005 vintages. Francois Despagne's 2005 wine will cost about $30 a bottle. And he's not so sure that global warming will be good for St. Emilion. But Despagne says the wines of Bordeaux have changed over the years — sometimes because of disease, sometimes because people's tastes have changed.

He says that if the climate changes by one or two degrees over the next 10 or 20 years, the wine he makes will change a little. "Perhaps it is possible to say it is a more Mediterranean wine," he says. But he thinks Bordeaux can adapt. As he speaks, Despagne's hands clasp together and his eyes dart upwards — as if checking with a higher authority about his predictions both for this year — and for the future.

Even without divine intervention, there are growing techniques that could be modified to account for the warmer temperatures. Right now, for example, it's common to remove leaves from the grapevines so the fruit gets more exposure to the sun. Perhaps in future the leaves will stay on longer.

And maybe it won't be necessary to remove as many grapes from the plants. Stephane Aplebaum is the vigneron, or winemaker, at Chateuau Quercy. He shows how many bunches of grapes are growing on a vine. Like most vignerons, Apelbaum refers to the grapes as berries.

"If you let all 25 bunches of berries stay on the vine until harvest ... the results is blah, tedious fruit," he says.

That's because there's not enough sun and water for that many grapes to reach a magnificent ripeness. So while the grapes are still green, most are sacrificed. Maybe with global warming it will be possible to keep more of the berries and make more wine.

Apelbaum says dealing with a changing climate is part of being a winemaker. "When I taste my wines and old vintages, amazingly I remember the weather," he says. "I remember the stress, I remember maybe some fights I had with people who were working for me and things like that. Everything is told into the bottle of the wine."

Some people have suggested that global warming will prompt people to head north, to start making wines where temperatures will be more like those Bordeaux used to experience. Apelbaum says that won't happen, because people are connected to their land.

"Maybe we'll have to change," he concedes. He thinks they might have to plant the Syrah grapes — a variety that is forbidden today by the strict wine classification rules of the region.

"But for the moment people don't seem to worry so much about it," he says. "They just adapt themselves."

And probably there will always be a market for wines produced with such devotion.

Produced by Jessica Goldstein

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.