Mysteries, mysteries, mysteries — everywhere I look there are puzzles, questions with no obvious answers: like why do I never see a baby pigeon? (There must be pigeon chicks somewhere, no? But where are they?). How come houseflies manage to land on a ceiling upside down without falling off? (At least I've never seen a fly lose its grip.) And now, here's a new one, sent to me by a reader who asks, "Why does wine cry?"

Why does wine what? I've never looked closely enough at a glass of wine to notice, but apparently, when you pour the wine in, swirl it a bit, then let it sit, something beautiful happens. The wine that sloshed around the inside of the glass doesn't fall back but stays there, above the beverage line, and starts to drip, forming a continuous little curtain of ... well, wine lovers call them "tears." Elegant little droplets slide down back into the wine, and then, for some weird reason, creep up again, then down again, then up/down, up/down, driven by some mysterious force that doesn't seem to end. What is causing this continuous "crying"? The answer, it turns out, is fascinating ...

I want to say a couple of things about Dan Quinn's video. He's not a professional science explainer; he's a grad student studying fluid mechanics at Princeton. As best I can tell, he wrote this piece, voiced it, drew the drawings, and edited it on his own. From his YouTube website, it seems he's been making videos at least since high school (when, in 2006, he produced a wonderfully weird 60 Minutes-style "investigation" of his classmates' addiction to the game Smash Brothers.)

A Golden Age?

Video isn't, I'm guessing, his main thing; it's what he does when he wants to exercise his storytelling muscles. In his grandparents' day, they would have had diaries, written letters, sketched, or maybe painted. This video thing — it's a new form of expression. And in the past five years or so, with the advent of YouTube and Vimeo, it's blossoming — and it's changing the world of science writing. Ten years ago, there were science reporters, scientists who wrote for public audiences and a few Carl Sagans and David Attenboroughs who did TV "specials" to explain the natural world. Now, if you know where to look, every morning on the Web you can find cartoons, illustrated essays, animations like Dan's, musicals, even dance explorations of science, all of them new, and some of them spectacularly good. We are living, I think, at the dawn of a golden age, where there are more ways, and more and more of them visually sophisticated, to learn how the world works. And it's all free! Yay! (Except, I sometimes wonder where that leaves us, the ones who get paid to do this for a living.)

But The Best Part Is ...

One last thing: For most people, science is what tickles you when you're in grade school learning about bugs and dinosaurs, and what dulls and drives you off when you meet the Krebs cycle in 9th grade, and you have to memorize long lists of chemical transactions. In high school, the pull-you-in storytelling stops, and for many, science becomes one long slog through short answer quizzes. But look what Dan did in his video: He shows you a puzzle — wine magically climbing a wineglass. He asks the right question: "Why?"

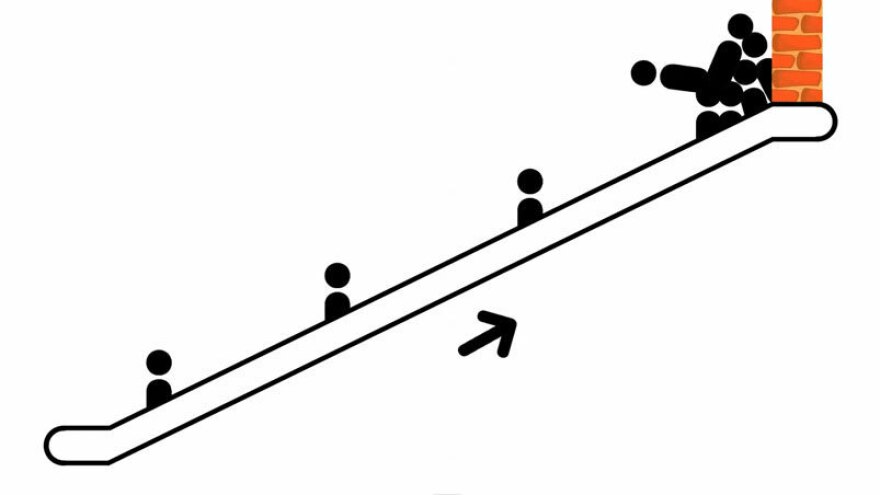

And the way he builds his answer — with a dab of laundry detergent scattering pepper flakes on a plate, with an escalator that can't unload its people — is totally engaging, true to the science, and makes you want to know more. That's the key. Science writing should be impregnating. It should make you lean in, not out. And now, thanks to the hundreds and hundreds of amateurs who have joined the game, there are impregnators everywhere. Bring on the Dans, I say. They spread the word — and the word needs spreading.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.