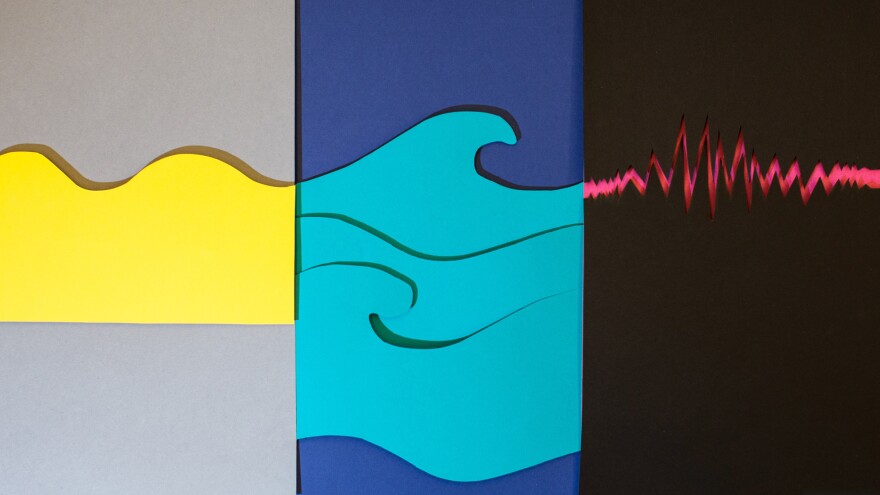

This summer, NPR's science desk is thinking about waves, of all kinds — ocean, gravitational, even stadium waves. But what is a wave, anyway? My editor asked me to puzzle that one out. And, to be honest, I was puzzled.

Is a wave a thing? Or is it the description of a thing? Or is it a mathematical formula that produces a curve that gives you the description of a thing?

Rather than pester a scientist with my somewhat philosophical questions, I decided to pester a philosopher. Marc Cohen is emeritus professor of philosophy at the University of Washington. He's sympathetic to my befuddlement.

"There's something about waves that can get you into kind of a mental funk," Cohen acknowledges. "Because you look at a wave — you can see them out on the water, and the wave moves across the water. Something's moving through space."

OK, I get that.

"But what is the wave exactly?" asks Cohen. "Scurry off to a physics textbook and it'll say that a wave is a disturbance that moves through a medium from one location to another."

OK, I think I get that, too.

"So it's really not a thing," Cohen says. "It's not made of stuff, like a chair is made of wood, or a football is made of leather.

"When a wave moves through the water, it's not really made of water," he says. "It's a wave in the water."

From a philosophical standpoint, Cohen says, you're better off thinking of a wave as a phenomenon, a thing that happens, like an event.

"Not what we Aristotelians would call a substance — like a football," Cohen says, "or an armadillo."

So a wave in the water is not like an armadillo. Got it.

But hold on a minute. If a wave is a disturbance moving through a medium, then what about lightwaves? They're a disturbance, and they don't need a medium to travel through. Cohen says his explanation only applies to physical waves — not electromagnetic waves or lightwaves.

"It's really mysterious how they get to move through empty space where there is no medium," says Cohen. "But if you want the answer to that question, you'd better talk to a scientist, not a philosopher."

I was afraid it might come to that.

But I note, in closing, that Cohen admits that waves have elusive properties that befuddle philosophers, too.

And that provides me with a wave of relief.

Science reporters at NPR are exploring all sorts of waves this summer. Find more of our favorites here.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.