Prescribed narcotic painkillers continue to fuel a nationwide opioid epidemic—nearly half of fatal overdoses in the United States involve opioids prescribed by a doctor.

But people don't seem to be avoiding the medications, despite the well-documented risks. In the latest NPR-Truven Health Analytics poll, over half of people surveyed, or 57 percent, said they had been prescribed a narcotic painkiller like Percocet, Vicodin or morphine at some point. That's an increase of 3 percent since we last asked the question in 2014 (54 percent), and of 7 percent since our 2011 poll (50 percent).

For almost three quarters of poll participants (74 percent), the prescription was for temporary acute pain, like from a broken arm or a dental procedure. Nineteen percent said they received the drugs for chronic pain.

"The drugs are like a two-edged sword," says Ron Ozminkowski, vice president of cognitive analytics in the value-based care pillar at IBM Watson Health, who works with Truven on the poll. "They're great for people who really need them for heavy duty pain, but they come with addiction risk and side effects."

Indeed, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention note that as many as 1 in 4 people who use opioid painkillers get addicted to them. But despite the drugs' reputation for addiction, less than a third of people (29 percent) said they questioned or refused their doctor's prescription for opioids. That hasn't changed much since 2014 (28 percent) or 2011 (31 percent).

Dr. Leana Wen, an emergency physician and commissioner of health for the City of Baltimore, says that's the problem. She says patients should more readily voice their concerns about getting a prescription for narcotics to make sure if it really is the best option.

If prescribing a narcotic painkiller is on the table, physicians should reference the opioid prescribing guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Wen says. Released in March of last year, the guidelines recommend trying non-narcotic medications or treatments first; lay out recommendations for when to prescribe the drugs; how to choose the appropriate painkiller and dosage; and how to assess risks. The guidelines are intended for primary care physicians, and not for those treating patients in end-of-life care or with cancer.

"Ask why," Wen says. "Often, other alternatives like not anything at all, taking an ibuprofen or Tylenol, physical therapy, or something else can be effective. Asking 'why' is something every patient and provider should do."

That message may be getting through. Many more poll participants expressed uneasiness about opioid painkillers, whether they'd been prescribed the drugs or not.

Almost half of people who said they hadn't used narcotic painkillers said they had concerns about them, up significantly from 30 percent in 2014 and 2011. Getting addicted to painkillers was their top concern (39 percent), followed by side effects (22 percent).

Among respondents who were taking opioids, 35 percent had concerns, down 1 percent from 2014 and 2011. As with prior polls, people taking opioids were more worried about side effects (38 percent) than addiction (27 percent).

We asked poll participants if they thought certain side effects were linked to taking opioids. More than three quarters thought addiction was associated with the drugs. They're right — nearly 2 million Americans abused or were dependent on opioids in 2014, and it's estimated that over 1,000 people a day wind up in emergency rooms across the nation for misuse of prescription opioids.

Two-thirds said they thought opioids were linked with constipation. And that's true; 41 percent of people taking opioids experienced constipation in one study, and another lists the side effect as "expected" with the use of opioids. There are even drugs being marketed specifically to combat constipation caused by prescribed narcotic painkillers.

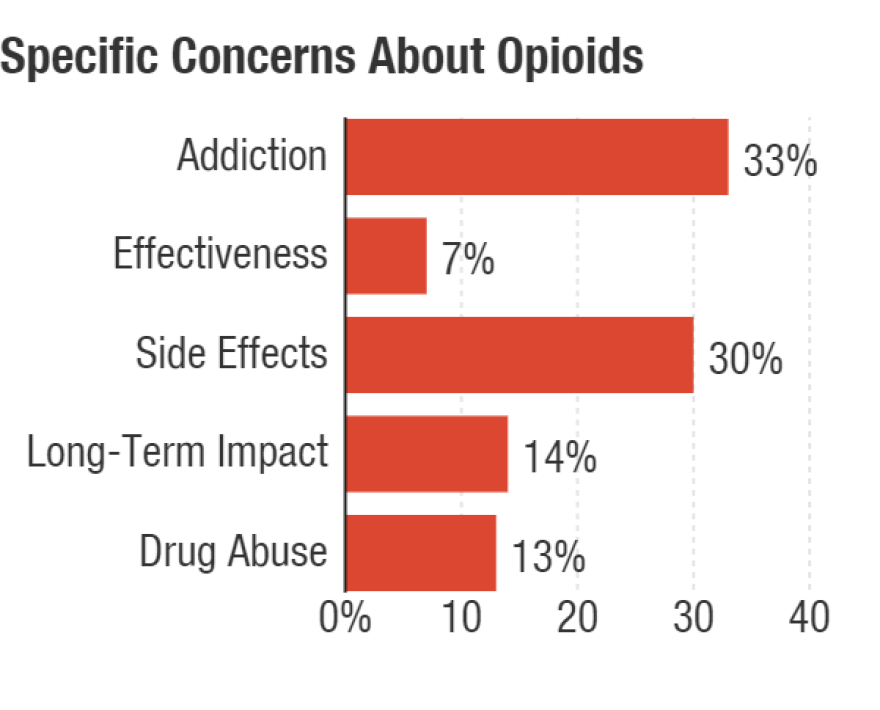

Aside from worrying about addiction or side effects, respondents also worried about narcotics' long-term health impact (14 percent) and their association with drug abuse (13 percent).

"Doctors have to think twice about how they use the tools in their pain killing tool kit," Ozminkowski says.

Wen agrees. "We must all take steps to fix this overprescribing. Heed the guidelines from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that say go low and go slow — start with the least harmful and least addictive and work your way up," she says. "We need to treat pain, but appropriately."

The poll gathered responses from 3,000 participants questioned over the phone and online from November 1 to 15, 2016. The margin for error is plus or minus 1.8 percentage points. You can find the complete set of questions and results here. Past NPR-Truven Health polls can be found here.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.