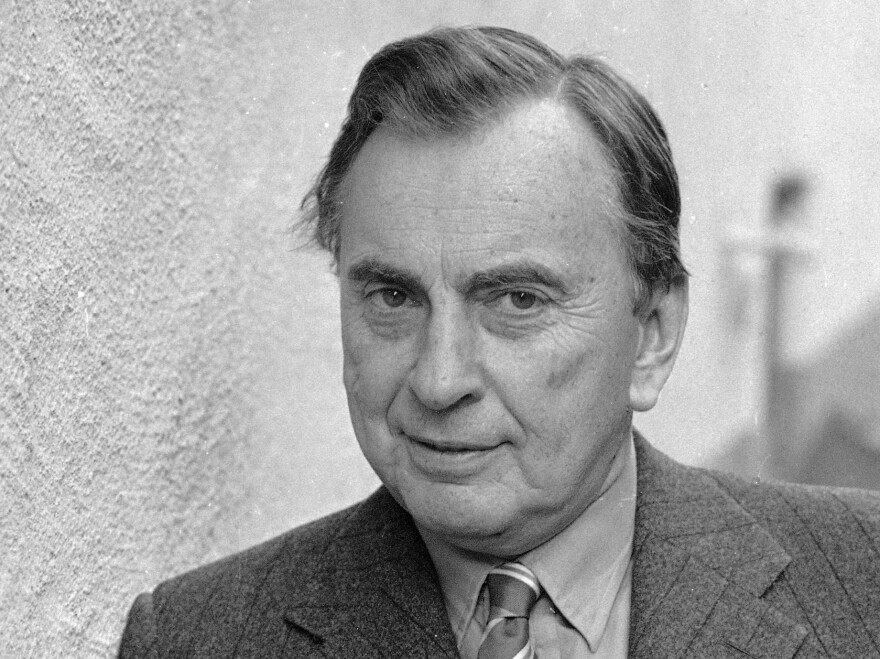

Gore Vidal came from a generation of novelists whose fiction gave them a political platform. Norman Mailer ran for mayor of New York City; Kurt Vonnegut became an anti-war spokesman. And Vidal was an all-around critic. His novels sometimes infuriated readers with unflattering portraits of American history.

He also wrote essays and screenplays, and his play The Best Man currently has a revival on Broadway.

Vidal died Tuesday at his home in the Hollywood Hills, from complications of pneumonia. He was 86 years old.

Born in 1925, Gore Vidal had a privileged background. His father was an All-American quarterback, an Olympic athlete, an instructor at West Point, and co-founder of three airline companies. His mother was a socialite and Broadway actress, and the daughter of a U.S. senator.

Despite that, Vidal told BBC broadcaster Sheridan Morley in 1993 that he was tired of being called patrician.

"I'm a populist, from a long line of tribunes to the people. And I believe the government, to be of any value, must rest upon the people at large, and not be the preserve of any elite group or class, or anything of a hereditary nature," he said.

Throughout his career, Vidal wrote and published essays that expounded his populist theme against what he called "the serious wrong turnings" America took in his lifetime.

"In 1950, after we won the second world war, which we regarded as our great victory, we were the No. 1 nation on Earth, economically and militarily," he said. "Well, Harry Truman, our then-president, decided to keep the country on a permanent military standing. Forever. The result is we're $4 trillion in debt. We don't have a public education system. We don't have health care. And we have two or three race wars going on. And we are falling back, back, back."

Vidal's novels included Burr, Lincoln and Empire — historical narratives that also offered a platform for his opinions.

But Time magazine critic Richard Lacayo says that's why he won't be remembered for his fiction.

"Whereas in his essays, he could make those arguments directly. And because he was such a funny, learned and also sometimes very bitchy observer, those essays are both a pleasure to read, and to argue with, if you will," Lacayo said.

Vidal's grandfather, Democratic Sen. Thomas Gore of Oklahoma, hoped that his grandson would also go into politics one day — a hope that was dashed, Lacayo said, when the young writer came out as bisexual in the early 1950s.

"Vidal's third novel was called The City and the Pillar," Lacayo said. "And many newspapers wouldn't advertise it because it was a novel with an explicit homosexual relationship in it — and a relationship that didn't involve a transvestite, or some miserable minor character, but it was sort of two regular American guys."

Vidal was banished from literary life and went to work for Hollywood — on screenplays including Ben Hur in 1959 and Caligula 20 years later. He also wrote plays — including The Weekend and TheBest Man, a prescient tale of a political campaign that Vidal turned into a screenplay in 1964.

Vidal eventually returned to fiction, and his ideas — and the way he expressed them in person — made him a favorite of interviewers and talk show hosts. He became a TV celebrity in an era when people like Johnny Carson still featured serious writers.

In 1993, Vidal lamented that literature had lost its place at the center of American culture:

"I said recently to a passing interviewer, 'You know, I used to be a famous novelist.' And the interviewer said, 'Oh, well, you're still very well known. People read your books.' And so I said, 'I'm not talking about me. I'm talking about the category. 'Famous novelist'? The adjective is inappropriate to the noun. It's like being — 'I'm a famous ceramicist.' Well, you can be a good ceramicist. You can be a rich ceramicist. You can be much admired by other ceramicists. But you aren't famous. That's gone."

And so now is one of the most pointed cultural critics of our time.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.