A dream of a day at the Centre Pompidou in Paris. We'd come out of a huge David Hockney exhibition, and my family and I were pooped. So granddaughters, their mother Myndy and I sat on a rim of the Stravinsky Fountain to rest a bit, while my son Josh took our picture.

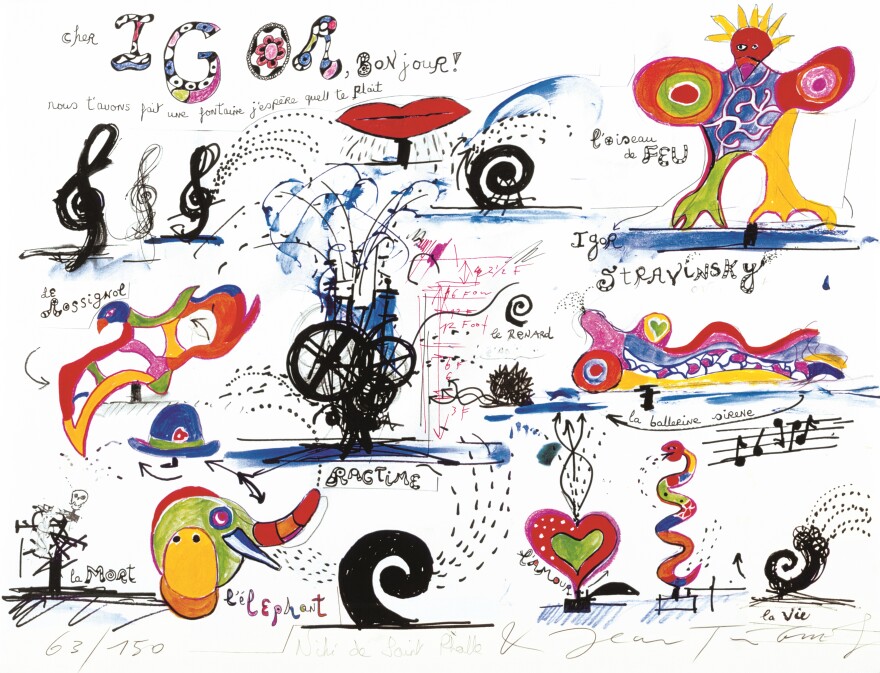

The fountain makes me smile four years later, as it did the first time I saw it decades ago. It's a 1983 collaboration between sculptors Jean Tinguely (he did the black mechanical parts) and Niki de Saint Phalle (the puffy colorful figures — something/someone in a crown, serpent, heart, lips).

I had no idea, sitting by that joyous fountain, the terrible sadness that had propelled one of its creators. I learned it, researching this essay.

On view now until early September at MoMA PS1 in Long Island City is the exhibition Niki de Saint Phalle: Structures for Life. It's her first show in New York, and focuses on her plans, sketches, models for various projects.

See the ruby red lips in the nighttime photo and that sketch? There's a scaled-down model in the exhibit. In the actual fountain, the lips spew water.

The artist was a beautiful woman. Full mouth. Bette Davis eyes. She'd modeled for Vogue and other magazines before making art. And had a complicated life. Searching, tormented, obsessed, joyful.

Catherine-Marie-Agnès Fal de Saint Phalle (her mother called her Niki when she was little and it stuck) was born in a suburb of Paris to French aristocrats who abandoned her on and off when she was little. New Yorker writer Ariel Levy reported that Niki's mother had a vicious temper, that when she was 11 her father abused her sexually, and in adulthood her brother and sister both died by suicide. Niki grew up in the U.S., moved to Europe in the 1950s and became an artist. It was an act of desperation.

She had had what she called a "mental breakdown" in the early '50s when she was 22, became suicidal, spent six weeks in a French asylum and, with no formal training, started to paint. "Art-making was an urgent thing for her," says PS1 curator Ruba Katrib. It helped her process her demons.

"I started painting in the madhouse," Saint Phalle once observed, "where I learnt how to translate emotions, fear, violence, hope and joy into painting. It was through creation that I discovered the sombre depths of depression, and how to overcome it." She believed art healed her.

Saint Phalle got famous in the early 1960s for attaching small plastic bags filled with paint onto canvases, covering them with plaster, and then shooting them with a rifle. Not a pretty sight:

The paint "bled" down the canvas. Katrib says the shots were against patriarchy, her father, maybe herself.

Her series of Nanas was less menacing, although they're not your benevolent grandma. In French "nana" is slang for "chick" — what the Sinatra gang used to call girls. Girls, many women, started resenting it. But Saint Phalle's Nanas are zaftig and happy-making in their brightly-painted polyester glory.

These fecund ladies are monumental. "I think I made them so large," she's quoted in The New Yorker, "so that man would look very small next to them."

"A form that would tower over men," curator Katrib says. "Women expressing their power, their freedom, their joy." They make us smile.

Ruba Katrib points out there's a spider in that big happy lady's crotch. "Also little heart shapes, birds, snakes. Dark and light. Always a mix."

Saint Phalle's life's work is in Tuscany. It took her almost 20 years to create Tarot Garden, a 14-acre sculpture park studded with monumental figures, some of them 40 feet high, made of sprayed concrete paved with mosaics of colorful china, glass and mirror shards, all inspired by tarot cards. The park opened to the public in 1998. It was her triumph over darker angels.

"She wanted to create a healing place for visitors," says Ruba Katrib. "Her idea was to transform pain into something joyous."

Sadly, ironically, Niki de Saint Phalle's own transformative experience with the garden may have led to her death. She was 71 when she died in 2002 of respiratory failure — her lungs possibly damaged by toxic fumes from materials she used over all those years, creating that life's work in Italy. Through her vivid, vital art, she also created her life. And gave us joy, each time we encounter it.

Art Where You're At is an informal series showcasing online offerings at museums you may not be able to visit.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.