In a video shared in a Facebook group, a narrator speaking Syrian-accented Arabic describes an elaborate, Roman-era mosaic depicting mythological figures and animals. The colored glass and stone in the mosaic are still vivid some 2,000 years after it was created.

A brief glimpse of sweatpants worn by the narrator is the only indication of who is speaking. Then the camera pans out to show that the mosaic still lies in the ground, uncovered in a field of dirt and rocks.

The Facebook group is one of more than 100 that archaeologists have identified as offering looted and illicit antiquities for sale. To counter this online trade, Facebook announced new rules in June that, for the first time, specifically ban the exchange, sale and purchase of all "historical artifacts" on its site and on Instagram, which it owns.

Previously, the company could invoke its general policy against the sale of stolen goods to remove pages selling artifacts that were clearly looted. But critics say it rarely did so. And they warn that Facebook's new policy won't have an impact unless it's enforced.

They say cracking down on the trade of looted antiquities is particularly critical as the coronavirus pandemic seems to have fueled more illicit sales of antiquities around the world.

"Above-board dealers, galleries, auction houses, even museums, they're shuttered. But the international black market is staying wide open for business. And in particular, Facebook never shuts down," says Tess Davis, executive director of the Antiquities Coalition, a Washington, D.C.-based organization aimed at combating cultural racketeering.

The value of trade in looted antiquities is difficult to determine, but some estimates put it at billions of dollars a year.

Davis says the consequences are far-reaching: Sales of looted antiquities help finance terrorism, facilitate money-laundering and are even linked to genocide.

The Facebook ban is "great for raising awareness," she says. "However, the impacts are going to be minimal so long as Facebook continues to rely on the public to report."

Facebook relies on complaints from users to investigate whether posts violate its standards. Unlike with other banned categories, such as gun sales, Facebook doesn't have an artificial intelligence program to help identify banned activity involving antiquities. And it doesn't hire experts who can easily recognize looted antiquities.

Amr al-Azm, a Syrian-American archaeologist and professor at Shawnee State University in Ohio, says many antiquities, such as the mosaic from northwestern Syria, are offered for sale on Facebook while still in their original location.

A co-director of the Antiquities Trafficking and Heritage Anthropology Research Project, he found that the antiquities-dealing Facebook groups are also giving advice from middlemen on how to loot — and what prices the pieces could command on the black market.

A Facebook document explaining its new policy cites research estimating that 80% of antiquities traded online are either looted or fake.

"It's a huge deal in that you've got Facebook finally recognizing that they have a problem on that platform, at least with regards to the trafficking in looted antiquities," says Azm.

ATHAR was one of the heritage organizations Facebook consulted in drafting its new policy. Azm says, though, without Facebook committing to enforcement, the ban will have little effect.

Artifacts offered in what archaeologists call a "loot-to-order" process are often shown with proof that the images are current, such as a narrator displaying a recent newspaper alongside the pieces.

"Mosaics are a very common item that are often offered for sale on Facebook, either on individual pages or in these groups that are specifically dedicated to either selling of looted antiquities or ... dedicated to basically crowdsourcing information on how to loot, where to loot," says Azm.

He says many of the antiquities offered by groups on Facebook are from conflict zones including Syria, Iraq, Libya and Yemen.

ATHAR — part of a group that filed a whistleblower complaint last month with the Securities and Exchange Commission alleging that Facebook has failed to police illegal activity on the site even though it's aware it goes on — says relying on user complaints shows the company is not serious about enforcing its own policies on illegal activity.

After repeated questions from NPR about specific posts that still offer antiquities for sale despite being reported for violations, a Facebook spokesperson, Crystal Davis, responded in an emailed statement: "We're committed to enforcing the policy; because the policy is relatively new, we are compiling training data to inform our systems so we can better enforce. It's an area where we are going to improve with time."

ATHAR co-director Katie Paul also notes Facebook charges a commission for sales from U.S. sellers on the site, allowing it to potentially make money from illegal sales.

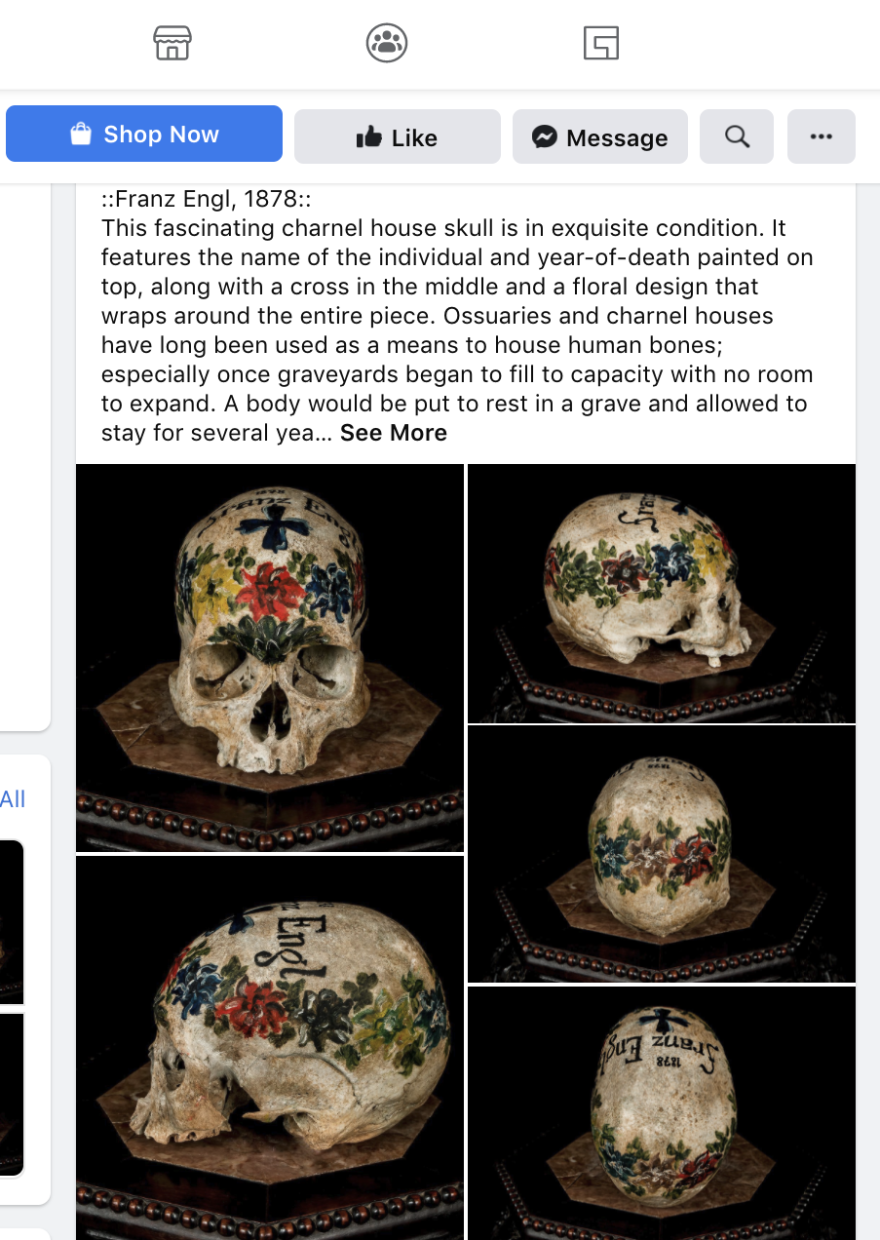

Some of the posts ATHAR has reported to Facebook — including several selling artifacts made of human remains — were deemed not to have violated Facebook standards and were kept on the site.

Azm and Paul have screenshots showing they reported about a dozen posts to Facebook since last month's ban on illegal antiquity sales came into force. One shows an elaborately painted sarcophagus containing a mummy, offered for purchase from an area in Upper Egypt known for antiquities trafficking. All of the postings explicitly noted that the items were for sale.

Screenshots that Azm and Paul took of Facebook's replies to their reports show that the company — which has a longstanding ban on trade in human remains — found only one of the posts contravened its standards.

"This is a multibillion-dollar entity and they won't invest in cleaning up their own site," says Azm. "Can you imagine how much more information is on the back end of this that they have access to? They're going to rely on two people who have day jobs, who spend their evenings scouring Facebook for evidence of crimes?"

One of the posts previously reported by ATHAR, which Facebook refused to remove at the time, dealt in Tibetan antiques. The seller's page, which in mid-July had been up for three years, included charts with shipping rates, price lists and videos of artifacts, many of them ceremonial objects made from human bones. Some posts even included the hashtag #humanbonesforsale.

Facebook deactivated the page after NPR asked why it had been deemed not to contravene company policy.

Azm says a major problem for cultural heritage advocates is that once Facebook determines that posts violate its policy, it simply deletes them rather than preserving them for possible prosecution — or further study by archaeologists and heritage experts. Facebook tells NPR it preserves the posts if asked by law enforcement agencies, but declined to answer whether that has ever happened.

Azm says valuable knowledge is irretrievably lost when Facebook deletes such posts.

"They're not part of documented collections that have been excavated properly by archaeologists, photographed and there's a record of them," says Azm. "The first time a human ... has ever laid eyes on these items is when you see this picture on Facebook. And once that item is sold, it disappears because it's looted, and it may never be seen again."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.