APR news told you last week about a plan to do away a red dye that used in food products. Student intern Samantha Triana introduced us to a Huntsville baker who’s already replaced chemical dyes for coloring made from vegetables. That’s not where the story ends. U.S. food producers also make things we eat using chemical additives. Some of them are not only unused in Europe, they’re against the law.

It’s evening rush hour at the Lokal Brugsen supermarket in Brabrand, Denmark. People in Alabama may be looking for brands like Campbell’s soup or Kellogg’s frosted flakes, but here in Denmark, it’s Castello cheese and Danish Crown meat products.

American shoppers may be right to be worried when it comes to food additives. There are major differences in how US and European food supplies are regulated—what chemicals are permitted and which aren’t. But when it comes to what these differences are, and why they matter, there’s one person to talk to…

“The food business operators, of course, are looking around in the public and see, what can we get through with here?” said Jannik Elmegaard. He works in Denmark’s Ministry of Food, Agriculture, and Fisheries. He says there are several steps to approving additives in Europe. Denmark is part of the European Union, or EU, so Denmark must adhere to the common rules the EU enforces.

“What can we actually get on the market. And if they can see there's no chance of getting their product on the market, they will cough, of course, not this, not spend the time and the money on the approval process. So that's the first step,” he observed.

And there are things that are common in food in the U.S. that are against the law in Europe. The website Everyday Health lists Titanium Dioxide for one. It’s an artificial color used in candy and sandwich spreads. You won’t find it in Europe. If there is a chance of the proposed additive being safe, Elmegaard says the second step of the process is the additive to receive approval from the European Food Safety Authority. That’s Europe’s version of the FDA.

“Then you have to make it obvious for the European Food Safety Authority that it is safe, that it is safe in the amounts that you want to use it in the types of food that you want to use it,” sais Jannik.

The third and final step is getting consent from the EU’s governing body, and the EU countries, that they accept the product for use. Countries cannot go back on the decision once it has been passed as law.

“This is…harmonized regulation,” said Jannik. “So, so if it, if it's decided between all, all member states with a qualified majority, then, then that is the rules that apply.”

The European Food Safety Authority uses a concept called the “precautionary principle” to guide its decision-making. The philosophy there is that it’s better to err on the side of caution, and not approve additives until they’re considered totally safe for human consumption.

“We have to use the so-called precautionary principle in the general food regulation,” said Jannik. “So it must be safe by all means, the product. And we have to use the intake data that are available, and if they show that it in some cases is not safe, that a product in some cases is not safe, then it can, of course, not be approved.”

Although countries cannot go back on EU food additive laws, they are free to create laws that are stricter than what the EU says. Denmark is a country that does so.

“I think Denmark is one of the more strict ones,” said Mads Rundstrom. He serves on the national committee Co-Op, a major Danish grocery chain.

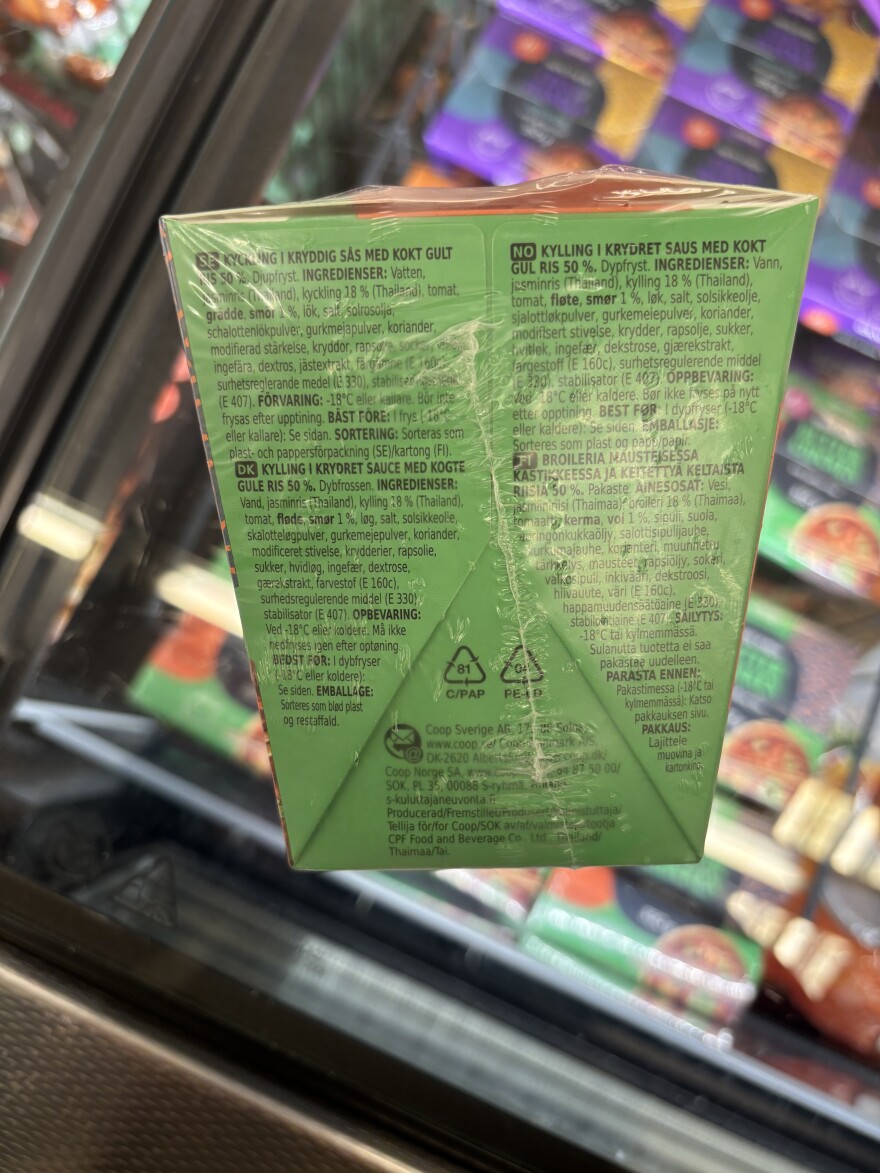

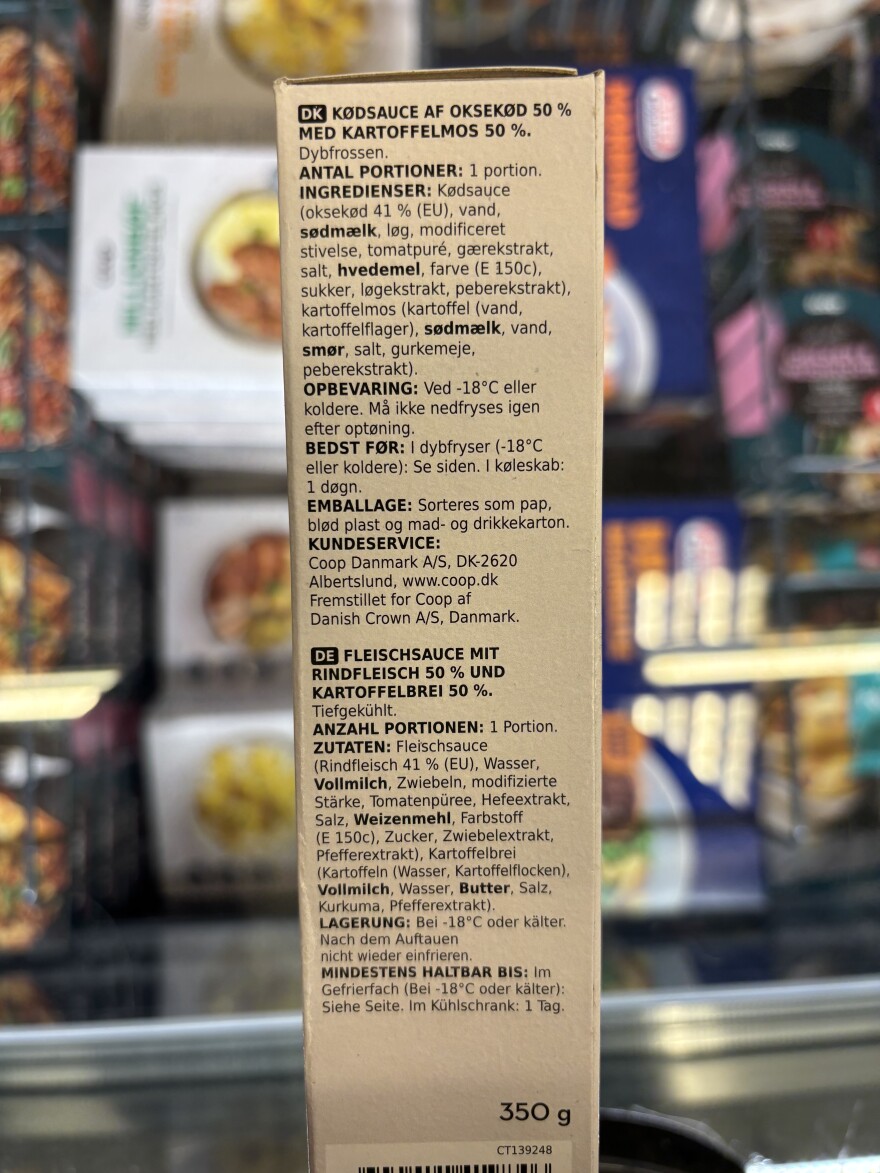

“I feel like there's probably some that are a bit more strict, but I feel like we are like in the hardliner group of it,” said Rundstrom. “But there's also, I mean, in general stuff. When I talk with, like the everyday Dane, and they're looking at some products, they're like, oh, there's all these e-numbers in so, yeah, these people are definitely aware of it.”

The e-numbers Rundstrom refers to indicate additives in European food products. Back in 2016, Co-Op was influential in getting Denmark to ban PFAs, a type of plastic found in many processed foods. Currently, Rundstrom is concerned about the presence of zero-calorie sodas in the Danish market. But, overall, he’s pleased with how Denmark has managed to protect consumer interest with its food additive legislation.

“I think the main challenge is that every time there is launched a new beverage, they mainly launched them as light or zero product which is containing a lot of aspartame, which is causing cancer, among a lot of other things, it's also damaging the brain,” he observed.

Meanwhile in the US, the situation couldn’t be more different. For Thomas Galligan, the difference in regulation between the US and EU boils down to difference in method.

“The European Food Safety Authority, EFSA, is required to apply what's called a precautionary approach when thinking about safety, whereas the FDA is under no explicit obligation to do the same,” he said.

Galligan is a scientist with CSPI, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, based in Washington DC.

“So the way that plays out is that sometimes the the it feels like the EU is is looking for evidence of safety, and if they don't have that evidence of safety, that chemical can't go on the market, whereas it feels like sometimes the opposite, and the FDA, where the FDA is looking for concrete evidence of harm before it takes action,” he said.

This loophole in the U.S. process has let chemicals that are banned in Europe be allowed into the US food supply. That the FDA says there’s not enough evidence to suggest they are unsafe.

“We saw this play out with the color additive titanium dioxide, where the European Union banned titanium dioxide based on evidence that it could possibly accumulate in the body and possibly damage DNA, whereas the FDA says that evidence is an important it's not conclusive, and so we're going to continue to say it's safe,” said Galligan.

Another major factor in allowing these additives in the US? The presence of a legal loophole written into the FDA itself. According to Galligan, when the FDA was founded in 1958, its procedure for evaluating food additive safety was basically the same as Europe’s.

An exception to this procedure was made for substances considered GRAS—or “generally recognized as safe.” These ingredients, such as flour and vinegar, wouldn't have to undergo the approval process. However, Galligan says this loophole was easily exploited by companies looking to cut costs.

“For decades, they've been introducing new, novel food substances into the food supply without getting FDA approval by exploiting this question poll, what they do is they hire their own experts or ask their own employees to say that this new substance is generally recognized as safe, and then they can just add it into food without even notifying the FDA, let alone getting FDA approval. No such process exists in the EU, so there's this gaping loophole in the US that is not available in the EU,” he said.

That’s not all. The presence of food additives has increased dramatically since 1997, when the FDA made the GRAS notification process optional. Galligan takes us through the process on that one.

“What they said was, formally, you don't have to tell us when you make a grass determination. And I think that did sort of open the floodgates. Some analysis done by our partners has shown that since 2000 something like 99% of new food ingredients in the US have come to market through the grass loophole, so it is being widely exploited, and I think it's because it's so much easier and faster for these companies than the formal approval process,” he said.

To the FDA, additives are innocent until proven guilty. In Europe, additives are guilty until proven innocent. Until the FDA’s legal loophole is closed and stricter regulations are introduced at the Federal level, it’s a good idea for Americans to be more mindful of the ingredients list on the foods they eat.

Editor's note—- The FDA was founded in 1906, not 1958. APR regrets the error.