"I saw so much segregation. I saw it and it hurt,” said 88 year old Vera Booker. She was a nurse at Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma, Alabama in 1965.

“And, Jimmie Lee didn't make it,” Booker added,

She was there 60 years ago, the night Jimmie Lee Jackson was shot by a state trooper. Eight days later he died. Then this happened.

“We could see police well, people on horseback, wearing gas masks with whips in their hands,” said Jeanette Howard-Moore. It was 60 years ago when voting rights marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama were attacked by state troopers.

“You can't breathe in tear gas billowing in the air,” said Howard-Moore. “You can't you just can't. And so everybody got up and started running.”

That day became known as "bloody Sunday."

“When the when Bloody Sunday came around in the United States, as far as recall, it was the ABC network that shifted from a documentary about the Nuremberg process against Nazis and switched to what was going on at the Edmund Pettus Bridge,” said Professor Jorn Brondal.

That reaction didn't come from the US, but rather from Europe. APR News spoke with students at the University of Southern Denmark on how they feel about Alabama's civil rights record. The discussion was Frank.

“They claim that everyone is equal, but they don't treat people equally, and that, I think, is the way we've at least been educated about like,” said student Benjamin Lundeegaard.

And, one name kept coming up.

“Danish youth know about Rosa Parks,” said Dr. Brondal. “When she died a couple of years ago, it was massive coverage of it in the Danish mass media.”

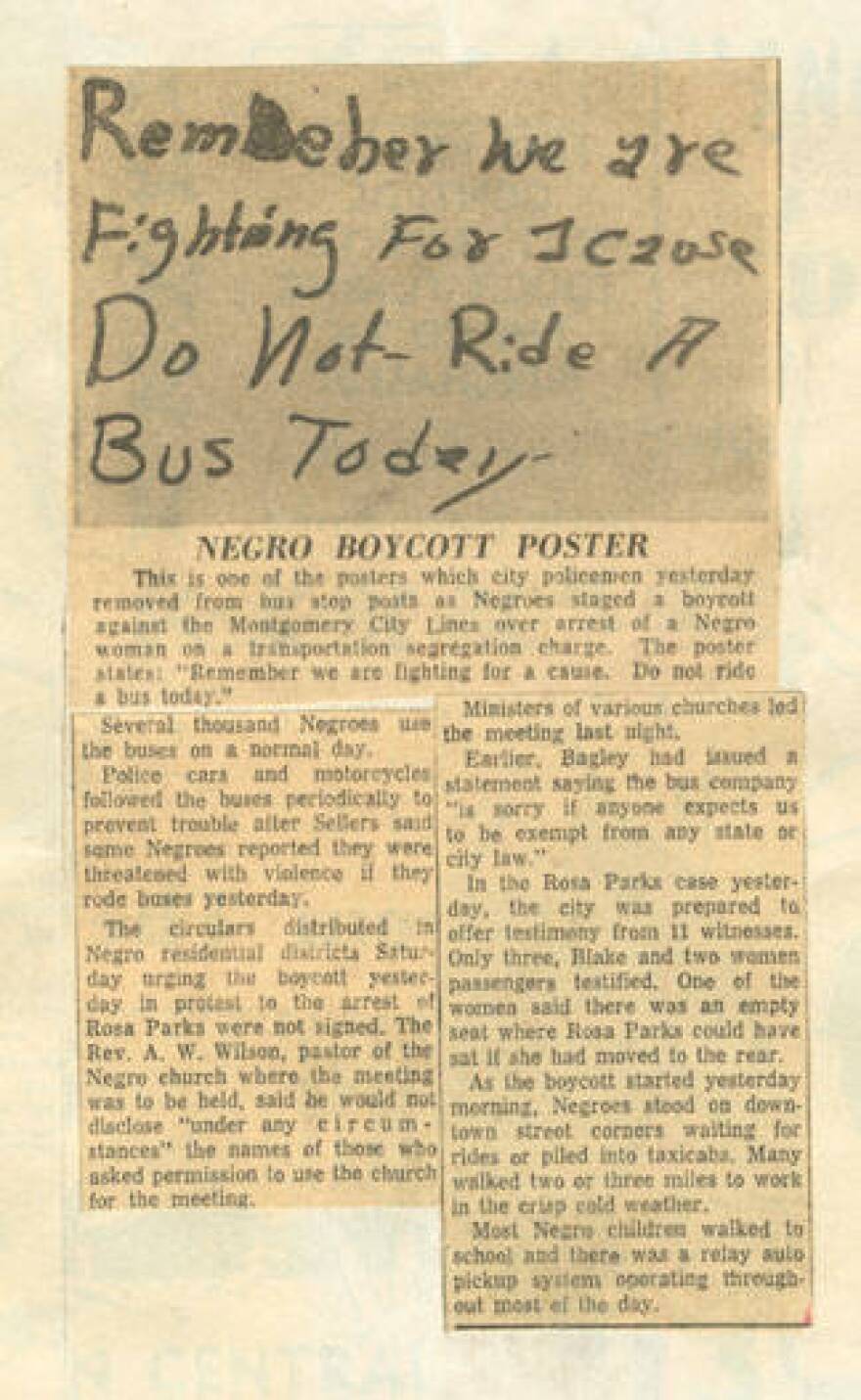

Rosa Parks arrest in 1955 sparked the Montgomery bus boycott. That was 70 years ago. APR listeners heard from someone on the front lines of this event on how they chose the man who would lead it.

“Joanne said, Well, why don't we get my pastor, Martin Luther King?” recalled Tuskegee attorney Fred Gray. “He has not been involved in civil rights activities. He haven't been here long, but one thing he can do, he can move people with his horse.

“The three proposals are briefly, number one, that more courteous treatment would come from the bus drivers. Number two, that the seating arrangement would be changed to a first come first served basis,” MLK said of the Montgomery Bus Boycott.

I'm Pat Duggins for the next half hour, join me and the APR news team for a program we call “…a death, a bridge, and a seat on the bus.”

“…at that time, we have been singing so we shall overcome and before I be a slave, be dead and buried in my grave.”

If you want to know what prompted the voting rights march on the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma in 1965 asked Bennie Lee Tucker. The Selma residents spoke with APR news ten years ago during the 50th anniversary of the attack, now known as Bloody Sunday.

“They were saying…let us… John Lewis and all of us, let us go to Montgomery,” said Tucker. So what we'll do, we'll take the body of Jimmy Lee Jackson and put it on the state capitol and let Governor Wallace know what he had done his people.”

Tucker knew about the killing of Jimmie Lee Jackson, but he wasn't actually there.

We met someone who was.

“My name is Vera Jenkins. My maiden name Booker,” said Vera Booker. She’s 88 years old.

“I saw so much segregation,” she recalled. “I saw it and it hurt.”

Booker went to school to study nursing that led to a job at Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma. Her life changed on the night of February 18, 1965

“…today, I rise to celebrate the life and legacy of Jimmie Lee Jackson,” said Alabama Congresswoman Terry Sewell, speaking on the floor of the U.S. House. “This 26 year old Marion Alabama native was brutally killed at the hands of an Alabama State Trooper on February 18, 1965…”

That night, Vera Booker was the nurse on the floor. Jimmy Lee Jackson was still alive when he arrived at Good Samaritan and he was talking.

“And then, of course, they carried him on up in hospital,” recalled Booker. “And he told me, he said, was the worst night I've ever seen in my life. It was just terrible.”

It took eight days for Jimmie Lee Jackson to die. Vera Booker was there the whole time.

“…and he just went on and on and on and just talked to me, and he said, But you know what he said after surgery, ‘my Booker, I don't ever believe I leave this hospital alive.’”

“It was the senseless murder of Jimmie Lee Jackson that served as a catalyst for the voting rights movement in Selma, Alabama. Jimmy Lee Jackson deserves to have his proper place in American history as a true agent of change,” Sewell contended.

“Yes, we're doing better over and we still but have a long way to go, because we have come a long, long way, but still have a long way to go and many more bridges to cross,” said Bennie Lee Tucker, whom at the beginning of our story.

He and planners of the Selma to Montgomery march talked about carrying the body of Jimmy Lee Jackson of the State Capitol, at least that was the initial idea.

“And so, it was decided that the casket were too heavy to carry fifty miles. And, so where we just walk? And we started out walking, and we were met with the tear gas,” recalled Tucker of the voting rights march that was met by an armed police posse.

“My dad was all set and ready and he was talking and watching the news,” said Jeanette Howard-Moore. She remembers that February when the movement came to her town.

“We as children knew something big was happening. We didn't know how big, but it was different than it had ever been in our house,” Moore recalled.

That something included children. Civil rights workers with bullhorns stood outside her high school in Marion telling students to skip class and march to town. Moore and her siblings followed along. She was only fourteen and didn’t know what would happen next.

“The police in Marion marched us from the drug store across the street, around the courthouse, to the jail,” Moore said.

The students were boarded onto school buses that took them to Camp Selma. That was a county prison camp holding Civil Rights demonstrators. Night came. There was no dinner. No heat. No parents.

“They had mentioned people might get hurt going across the bridge. Kids couldn't swim. It was just dangerous,” she said.

Moore and her siblings stayed in Camp Selma for four days, but that was just the beginning. A couple of weeks later, their father dropped them off on Sunday, March 7 at Brown’s Chapel Church for the march to Montgomery. Moore didn’t want to go.

We could see the police. People on horseback wearing gas masks with whips in their hands. The horses even had something over their face and they were agitated. They were all across the top of the bridge,” Moore described.

The troopers, horses, and sound of popping cans of tear gas got closer.

“You can't breathe in tear gas billowing in the air,” Moore recalled. “And so everybody got up and started running. I don't know what happened.”

The last thing Moore remembers was looking up at the belly of a horse. She came to at the church with a blanket over her head. She thought she was dead. She was taken to Good Samaritan Hospital for her head injury. A week later, she walked the 54 miles in the final march to Montgomery showing that she was okay.

A few years later, Moore moved to Chicago. Leaving Selma and the memories of 1965 behind. Then her family started asking questions, Moore realized she was a part of history.

“I didn't forget,” Moore insists. “I didn't just tell my story to my children, to my family. Just maybe in bits and pieces, but not just tell my story and all of the events. And I kind of think that the majority is like that.”

“I was arrested on two occasions,” said Dianne Harris, another young marcher. “I proudly wear a badge of honor as being a jailbird.”

So like Moore, Harris left school for a student March. She was 15 when she was sent to that same Camp Selma, and later to the National Guard Armory, where she was struck by a cattle prod that sent an electric shock through her body. Harris was at Bloody Sunday and the final march two weeks later, when they finally made it to Montgomery, but she got there in an unconventional way.

“We were told to bring our quilts because back in the day, Black folk didn't own don't own sleeping bags," Moore recalled, "Bring your beautiful quilts that your ancestors made because you're going to have to sleep on the grounds of St. Jude Catholic School,” said Harris.

Harris was proud to stand at the capital and hear Dr. King speak.

“We have been told all these marches would never get to Montgomery,” she said. “But Dr. King gave his famous speech and at the end, I'm going to try and quote some of the words he said, ‘They said, we wouldn't get here. We'd only get here over their dead bodies. But we are here and we are here to tell the world ain't going to let nobody turn me around.’”

Just like these girls recorded in Selma in 1965, Ain’t gonna let nobody turn me around is the first freedom song Harris learned. Now she guides Civil Rights tours in Selma. On August 6th, 1965, President Lyndon Johnson passed the Voting Rights Act because of marchers like Jeanette Moore, Dianne Harris, and John Lewis.

If you want a picture of how Danes and other Europeans view the US, you could do worse than a five-student focus group at the University of Southern Denmark (SDU). My name is James Niiler, and I cover stories for APR from my hometown in Arhus, Denmark. That includes how Europeans feel about Alabama's civil rights record.

All students are either undergrad or graduate students in SDU’s American Studies department. Four students in this group are Danish, and one is Italian—Elena Berardi, age 26. She’s finishing her master’s degree. And to hear her, you’d think the initial European impression of the U.S. is a positive one.

“My maternal grandparents were from the southern part of Italy,” she says. “My grandfather was liberated by the Americans during the Second World War, so he always said, ‘Okay, those Americans, they were very great to us and they helped us.’

It’s when you get into the topic of civil rights in the US that things get dicey.

Graduate student Benjamin Lundgaard, age 26, brings up the concept of the ‘American dilemma.’ “The idea that America has, that everyone is equal, right? Written into the Declaration of Independence,” he says.

“(Americans) claim that everyone is equal, but they don't treat people equally. And that, I think, is the way I’ve been educated about the Civil Rights Movement, in comparison to our movements (separate) from the US.”

This year, Alabama is observing the sixtieth anniversary of Bloody Sunday, the attack on Black voting rights marchers on Selma’s Edmund Pettus Bridge. But it’s not the only anniversary being observed this year.

When the students are asked what comes to mind when they think of the US and civil rights, there’s one figure they repeatedly mention: Rosa Parks, and how she began the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott.

Rosa Parks is not only a regular topic of conversation among students, but among their professors too. Dr. Jørn Brøndal is an author, historian, and professor of American Studies at SDU with a long interest in Black history.

He’s even written a textbook on the subject, that covers the story of Black America from Colonial times to the Black Lives Matter protests of 2020.

“When she (Parks) died a couple of years ago, there was massive coverage in the Danish mass media,” Brøndal says.

“Danish youth know about Rosa Parks. Know about Martin Luther King. They probably haven’t heard about Fred Shuttlesworth. They probably haven't heard about Bob Moses, and maybe some have heard about John Lewis.”

While Bloody Sunday may not make much of an impression on the focus group, Brøndal says the impact the incident had on the United States was clear to see even from Denmark.

“When Bloody Sunday came around in the United States, as far as I recall, the ABC Network shifted from a documentary about the Nuremberg process against Nazis, and switched to what was going on at the Edmund Pettus Bridge.

“And I think that that kind of shock that you saw in parts of the United States that was probably replicated in many European countries.”

What Brøndal describes in his textbook and his students call the ‘American dilemma’ is as old as America itself. That the United States was founded on a revolutionary promise of equality, but the ‘land of the free and home of the brave’ has often failed to deliver that promise to all of its citizens.

Brøndal recites the opening lines to the Declaration of Independence.

“We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights..."

“That is what sort of interested me, and also the fact that the person who at least was the main author of the Declaration of Independence was Thomas Jefferson, was an enslaver.”

When it comes to Black Americans themselves, Danes tend to hold stereotypes that don’t always line up with reality. The story of Black America is a complex one, marked by tragedy and triumph, discrimination and acceptance, poverty and wealth. Brøndal says these accounts often occur at the same time.

“Many Danes also associate African Americans mostly with poverty. They don’t realize that there's a huge middle class, for instance, in Atlanta and in many other American cities. They don’t realize that, but simply associate African Americans with inner city violence and inner city poverty, and with maybe a little bit of Mississippi poverty.”

Back in the student focus group, it seems like undergrad Lukas Fausing, age 22, can’t help but feel what’s going on in the United States is reflected in how Denmark treats its own minorities.

“I think (it’s similar) as in the US, where minorities might feel like second class citizens in some way,” he says.

“It’s been covered that when refugees or immigrants with a foreign-sounding name search for jobs and they write their résumé but their name is not something that sounds Danish, they get rejected.”

Mattias Vingaard agrees, saying how America’s Black Lives Matter movement focused on racially-based policing, a similar situation to what exists in Denmark.

“Some people have criticized the Danish police for going to the so-called ghettos more often than other places. So although the problem is not the same, or at least it's not that extreme, you still have the debate and something similar is happening."

As the world gets closer to December’s sixtieth anniversary of the start of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, Rosa Parks may come up in conversation more and more in Denmark and Europe.

“I think it's because she was a woman, and I’m very proud to say that as a woman.

“She just switched seats on a bus. I think that was actually the very revolutionary move that she made.

“She did something that I think a lot of people wanted to do, but she had the guts to do it.”

“Who can tell me what Rosa Parks did? Why she’s famous,” asked Donna Beisel to a roomful of fourth graders.

Fourth graders from Tuscaloosa’s Rock Quarry Elementary School sit cross legged on the floor of the Rosa Parks museum in Montgomery. The room is full and the students wave paper fans as if they are the ones on a crowded public bus. Museum director Beisel sets the stage for their tour.

“That’s right, she refused to give up her seat to a white man, and she was arrested for her defiance,” She continued.

I'm APR Gulf coast correspondent Cori Yonge. Most of the students already know that Parks was on her way home from work when she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. She was arrested for her defiance. Here, these youngsters watch captivated as a movie recounts Parks’ actions. It plays against the back drop of a real, 1950s Montgomery public bus.

It clearly makes an impression – leaving the fourth graders with a better understanding of Parks’ courage and the people who joined with her to end segregation. Here’s Sadie Young, Harrison Hurd, and Callie Spring.

“She was a great person,” said Sadie.

“Very serious woman and she stands her ground,” said Harrison.

“Very big impact,” said Callie.

A big impact is what many Americans remember about Parks and her role in the bus boycott. But the fine details of her life are often forgotten. At the time of her arrest, contrary to newspaper accounts of the day, Parks wasn’t physically tired. She was just tired of being mistreated.

“What made you decide at the first part of the month of December 1955 that you had enough?” asked Rogers.

“The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose.”

Parks explained it this way in a 1956 public radio interview with KPFA journalist Sidney Roger. The interview was one of many Parks gave as a board member for the Montgomery Improvement Association. That’s the organization founded to run the boycott. After her arrest, Parks crisscrossed the country promoting the bus boycott and raising money for the cause. Though soft spoken, her words were fierce.

“Why weren't you frightened?” Rogers inquired.

“I don't know why I wasn't but I didn't feel afraid I had decided that I would have to know once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen even in Montgomery, Alabama,” Parks responded.

When police arrested Parks, she was a 42-year-old seamstress for the Montgomery Fair department store. That’s where Black citizens were allowed to shop but not allowed to try on clothing or eat at the lunch counter. H

Here’s Donna Beisel.

"For probably about 20 to 30 years after that, she was kind of shuffled to the back and, you know, thank you for your service kind of thing. Now, step aside. Um, we're going to have other leaders kind of take the spotlight,” she said.

Despite the hardships, Parks never wavered in her dedication to human rights.

“She had 20 years of activist experience before the bus boycott and decades after, really, until she physically couldn’t anymore,” said Beisel.

Parks died in 2005 at the age of 92. Today there are new efforts to unfold the Rosa Parks’ story beyond her seat on the bus. With the 70th anniversary of the bus boycott, the museum is kicking off a campaign to acquire the Rosa Parks archives from the Library of Congress.

“Kids have this, and some adults, have this idea of her as this almost mythical being that you know, I can never do what she did,” said Beisel.

Beisel says housing the archives at the museum will round out the Rosa Parks’ story - perhaps inspiring future generations to reach for change in their communities.

Dce

This is from December 5, 1955. I'm APR student reporter Torin Daniel. Doctor Martin Luther took a vote among the Montgomery Improvement Association. It would take the Montgomery Bus Boycott from a one day event to one lasting 381 days,

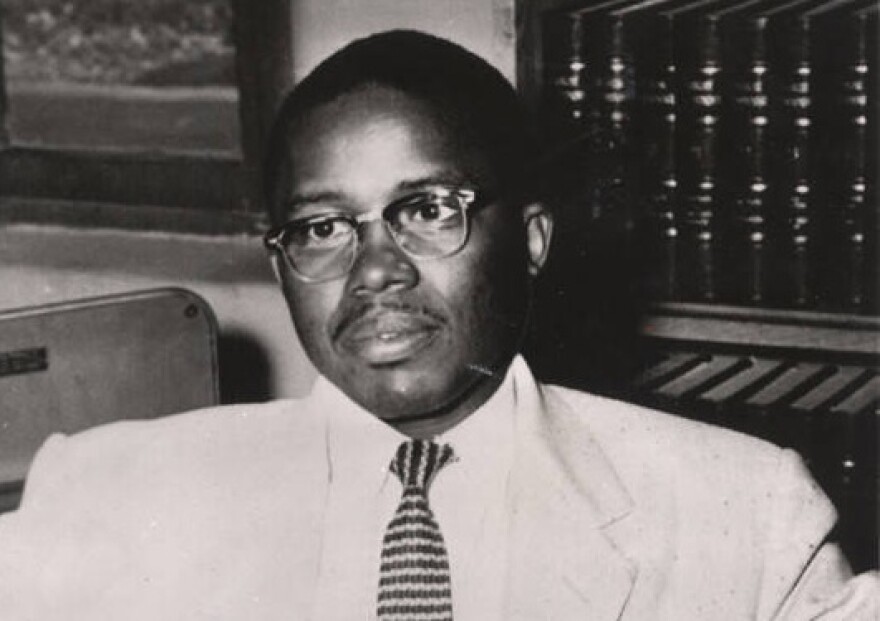

“The greatest planning I did, as far as planning for a a an event, was the planning that Joanne and I made in her living room for the Montgomery bus boycott,” said Fred Gray.

He was the attorney to both MLK and Rosa Parks. As far as the Montgomery Bus Boycott was concerned, Gray was in the middle of it. The Joanne Robinson he referred to, plays a big role later in this story, APR News spoke with gray about the Montgomery Bus Boycott back in 2018 This is the first time this audio has been heard in public.

“There's some misunderstanding on some people, part because some people think he came to Montgomery to start a civil rights movement,” Gray continued.

He was referring to his client, Dr Martin Luther King, Jr. He recalled how choosing King to lead the bus boycott wasn't guaranteed. Two other names came up, Ed Lewis and Rufus Nixon. They were both well known civil rights activists. Remember the Joanne Robinson that Fred Gray mentioned earlier? He says she was the group leader who made her feelings known.

“Joanne said, ‘Well, why don't we get my pastor, Martin Luther King. He has not been involved in civil rights activities. He haven't been here long. But, one thing he can do, he can move people with his words,’” Gray recalled.

“He not only could speak, but he was a very good listener, and he had a good sense of humor, even to the extent of telling some jokes sometimes that he wouldn't be able to tell in the pulpit. But he was a very good practical person,’ Gray continued.

“One of the best things we decided to do was to ask the people just to stay off of the bus for one day. Most people can make arrangements to get to where they need to go for a day,” Gray recalled.

The problem of transporting people during the longer boycott was solved by enlisting black owned funeral homes in Montgomery. They had cars and offered rides to African American city residents who needed a way to get around townl. Along with red gray APR news heard from another Montgomery resident with a unique relationship to Dr King.

APR listeners first met Nelson Mauldin in 2018. We visited the barber shop he owned in the 1950s it was here and who he first met in 1954 one year before the bus boycott that's the point.

“Well, the first thing it came in the shop like any new customer,” said Nelson Mauldin, Dr King's barber in Montgomery.

“When I finished cutting his hair. I gave him the mirror to say it like his haircut. So he told me, pretty good. So when you tell a barber pretty good, that was an insult,” Malden said.

Dr King became a regular in Maldon's barber chair, and he recalled the first day of the Montgomery bus boycott.

“Oh, yeah. Well, you could tell, because the first day the boycott started, we was in the barber shop, and one of the customers a here come the bus, and we all ran to the wonder to see there was a black man standing on the corner across the street from the barber shop. And we looked, we couldn't see what the man got on and off,” Malden said. “When the bus pulled off, the man was still standing. We saw, Oh, Lordy! We thought (boxer) Joe Lewis had knocked out Max Schmelling.

381 days later, King called for an end to the boycott. The event became engraved in civil rights history, and Fred Gray says, King became an international figure.

“…and all of it happened here in Montgomery, Alabama, and Dr King was serving as spokesman of the group during the Montgomery bus boycott. And I'm happy that I served as his legal advisor," said Gray.