Rosa Parks is often called the mother of the modern day civil rights movement. Her refusal to stand up on a city bus so a white man could sit down sparked the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Tomorrow marks the 70th anniversary of the movement that ended segregation on public buses in Alabama's capitol city. APR takes a deeper look at Parks life and the act of defiance that came at great personal cost to the civil rights icon.

“Who can tell me what Rosa Parks did? Why she’s famous,” asked Donna Beisel to a roomful of fourth graders.

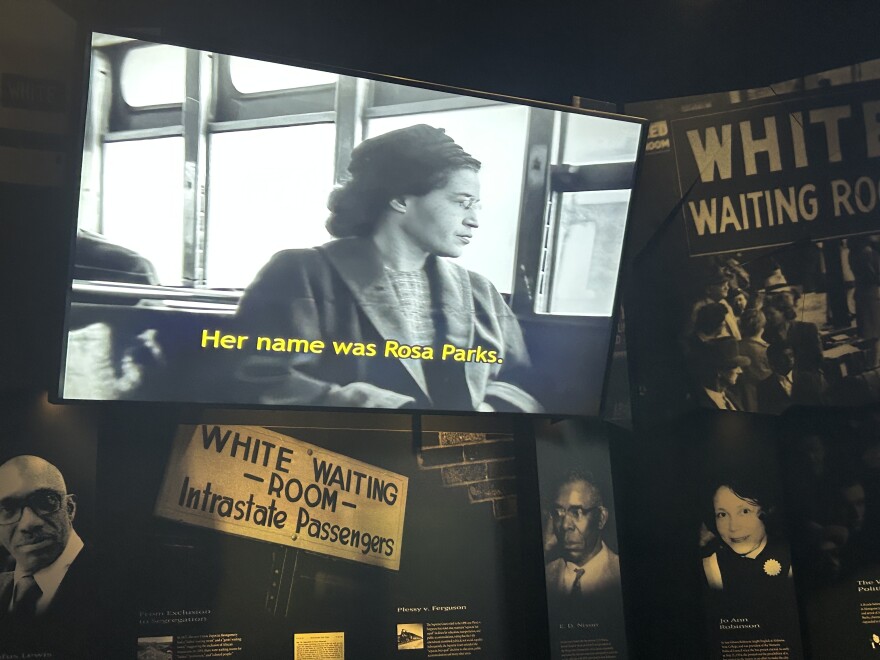

These youngsters from Tuscaloosa’s Rock Quarry Elementary School sit cross legged on the floor of the Rosa Parks museum in Montgomery. The room is full and the students wave paper fans as if they are the ones on a crowded public bus. Museum director Beisel sets the stage for their tour.

“That’s right, she refused to give up her seat to a white man, and she was arrested for her defiance,” She continued.

Most of the students already know that Parks was on her way home from work when she refused to give up her seat on a Montgomery bus. She was arrested for her defiance. Here, these youngsters watch captivated as a movie recounts Parks’ actions. It plays against the back drop of a real, 1950s Montgomery public bus.

It clearly makes an impression – leaving the fourth graders with a better understanding of Parks’ courage and the people who joined with her to end segregation. Here’s Sadie Young, Harrison Hurd, and Callie Spring.

“She was a great person,” said Sadie.

“Very serious woman and she stands her ground,” said Harrison.

“Very big impact,” said Callie.

A big impact is what many Americans remember about Parks and her role in the bus boycott. But the fine details of her life are often forgotten. At the time of her arrest, contrary to newspaper accounts of the day, Parks wasn’t physically tired. She was just tired of being mistreated. Parks explained it this way in a 1956 public radio interview with KPFA journalist Sidney Roger.

“What made you decide at the first part of the month of December 1955 that you had enough?” asked Rogers.

“The time had just come when I had been pushed as far as I could stand to be pushed, I suppose.”

The interview was one of many Parks gave as a board member for the Montgomery Improvement Association. That’s the organization founded to run the boycott. After her arrest, Parks crisscrossed the country promoting the bus boycott and raising money for the cause. Though soft spoken, her words were fierce.

“Why weren't you frightened?” Rogers inquired.

“I don't know why I wasn't but I didn't feel afraid I had decided that I would have to know once and for all what rights I had as a human being and a citizen even in Montgomery, Alabama,” Parks responded.

When police arrested Parks, she was a 42-year-old seamstress for the Montgomery Fair department store. That’s where Black citizens were allowed to shop but not allowed to try on clothing or eat at the lunch counter. Her husband Raymond was a barber at Maxwell Airforce Base. Museum director Donna Beisel says the 1956 bus boycott wasn’t Parks first foray into activism.

“So she really got started in the 1930s with the Scottsboro Boys case,” she said.

The Scottsboro Boys were nine young Black men wrongly convicted and sentenced to death in Alabama for raping two white women. Rosa and Raymond worked to free the men. Parks next civil rights role was as an active member of the Montgomery Chapter of the NAACP. But Beisel says Parks would pay her steepest price for her part in the boycott.

“She and Raymond lost their jobs,” Beisel recalled. “They were constantly receiving threats.”

Though only a small child at the time of the boycott, 73-year-old Meta Ellis remembers those threats to Parks and other organizers. Her father was Reverend Robert Graetz – the white minister of Montgomery’s all- Black Trinity Lutheran Church. Like Parks, Graetz was instrumental in organizing the boycott.

“And there were a lot of times when the Klan would be driving by our house slowly, letting us know that we were being watched with the rifle out the window and the phone calls coming every day,” said Ellis.

The intimidation didn’t deter Parks. She and Raymond were among the first to arrive when the KKK bombed the Graetz family home in 1956.

“She was there in the midst of all the chaos, uh, sweeping up messes in the kitchen and picking up broken glass. Um, this was the kind of person she was,” said Ellis.

In 1957, with the boycott over, the families separated. Unable to find jobs in Montgomery, the Parks moved to Detroit where Rosa and Raymond’s luck was no better. A 1959 federal tax return shows the couple earned a combined income of little more than 600 dollars. And a 1960 Jet Magazine profile describes Parks as “a tattered rag of her former self. Here’s Donna Beisel.

"For probably about 20 to 30 years after that, she was kind of shuffled to the back and, you know, thank you for your service kind of thing. Now, step aside. Um, we're going to have other leaders kind of take the spotlight,” she said.

Despite the hardships, Parks never wavered in her dedication to human rights.

“She had 20 years of activist experience before the bus boycott and decades after, really, until she physically couldn’t anymore,” said Beisel.

Parks died in 2005 at the age of 92. Today there are new efforts to unfold the Rosa Parks’ story beyond her seat on the bus. With the 70th anniversary of the bus boycott, the museum is kicking off a campaign to acquire the Rosa Parks archives from the Library of Congress.

“Kids have this, and some adults, have this idea of her as this almost mythical being that you know, I can never do what she did,” said Beisel.

Beisel says housing the archives at the museum will round out the Rosa Parks’ story - perhaps inspiring future generations to reach for change in their communities.