Recently I have been soaked in books about the vicious partisan debate at the University of Alabama during Reconstruction and the disgusting privileged behavior of the arrogant rich in Buckhead, Atlanta. It was time for a palate cleanser.

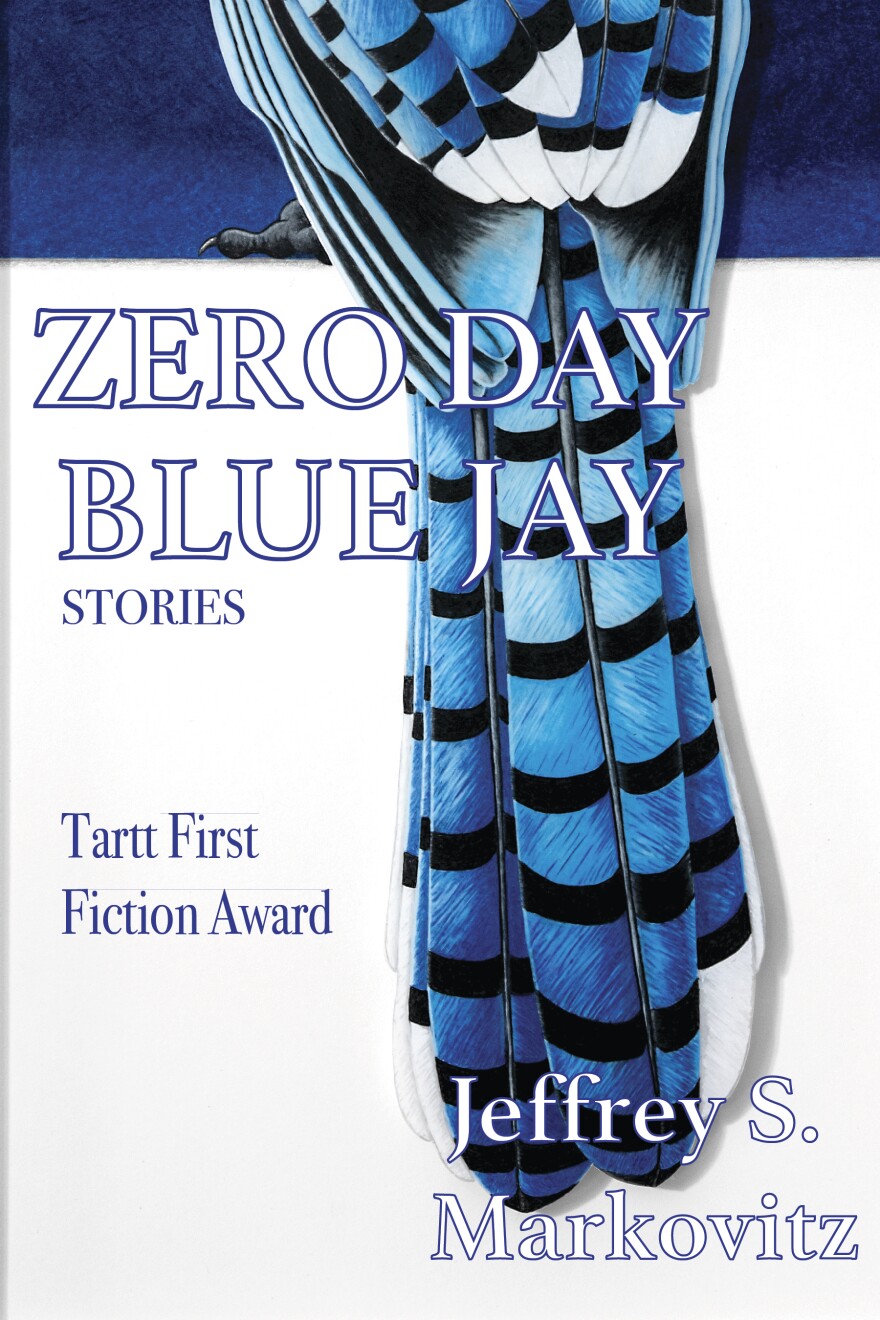

The 15 stories of Jeffrey S. Markovitz’s “Zero Day Blue Jay,” a Tartt First Fiction Award winner, are set in Germany, El Salvador, New York City, West Virginia, Utah, Oxford University, I think, and in Philadelphia where Markovitz, an English department academic, lives and works.

Readers of short stories are down in number, but I’m still a fan. Any collection will be uneven, but the reader knows, as when listening to a stand-up comic, if you don’t like this one, another will be along in a moment.

Maybe my favorite in this collection is “Threads.” The narrator did not understand why her mother, a German Jew forced to labor in a screw factory, did not somehow rebel more, violently resist. As the 8-page story, proceeds, we learn that her mother had, furtively, every day, managed to file down a screw or two, and one day, a German plane crashed as a result of this wartime, anti-Nazi, Resistance butterfly effect.

Markovitz is clearly a lefty-leaning academic and intent on declaring some social truths. In the story “Self-portrait,” set in 1952, an FBI agent is distressed at the disproportionate amount of attention being paid to the mugging death of Amber, a 23-year-old white woman, her picture in the paper every day and a large reward offered for information, when little attention is paid to other victims, usually Black young men, in Queens, New York, their cases handled by the local police, their killers rarely found.

A more mysterious story, and academic in the extreme, is “An Anthologist of Ideas,” in which a group of world-famous intellectuals, “experts” in literature, physics, art, psychology, business, are enticed by luxurious accommodations and huge stipends to meet and discuss the great question: WHY are we here?

They seem to be in Oxford, and sponsored by a man of mystery known only as Mr. A. They meet, discuss, offer possible reasons, take copious notes. They eat; they drink a lot. Two begin an affair. They are humans, after all. They all know, in fact, knew already, that no answer to the secret of life is possible but are still shocked when they learn why they were assembled.

Several stories in this collection are domestic, family stories. I was impressed by Markovitz’s explorations of another Big question: human love. A couple are parent/child stories, more specifically father/son stories, in which understanding may come late in life, even after the father’s death. A child can never really know how much his parent loves him or match that parent’s love. That insight may come one day when one realizes how much one loves one’s own child.