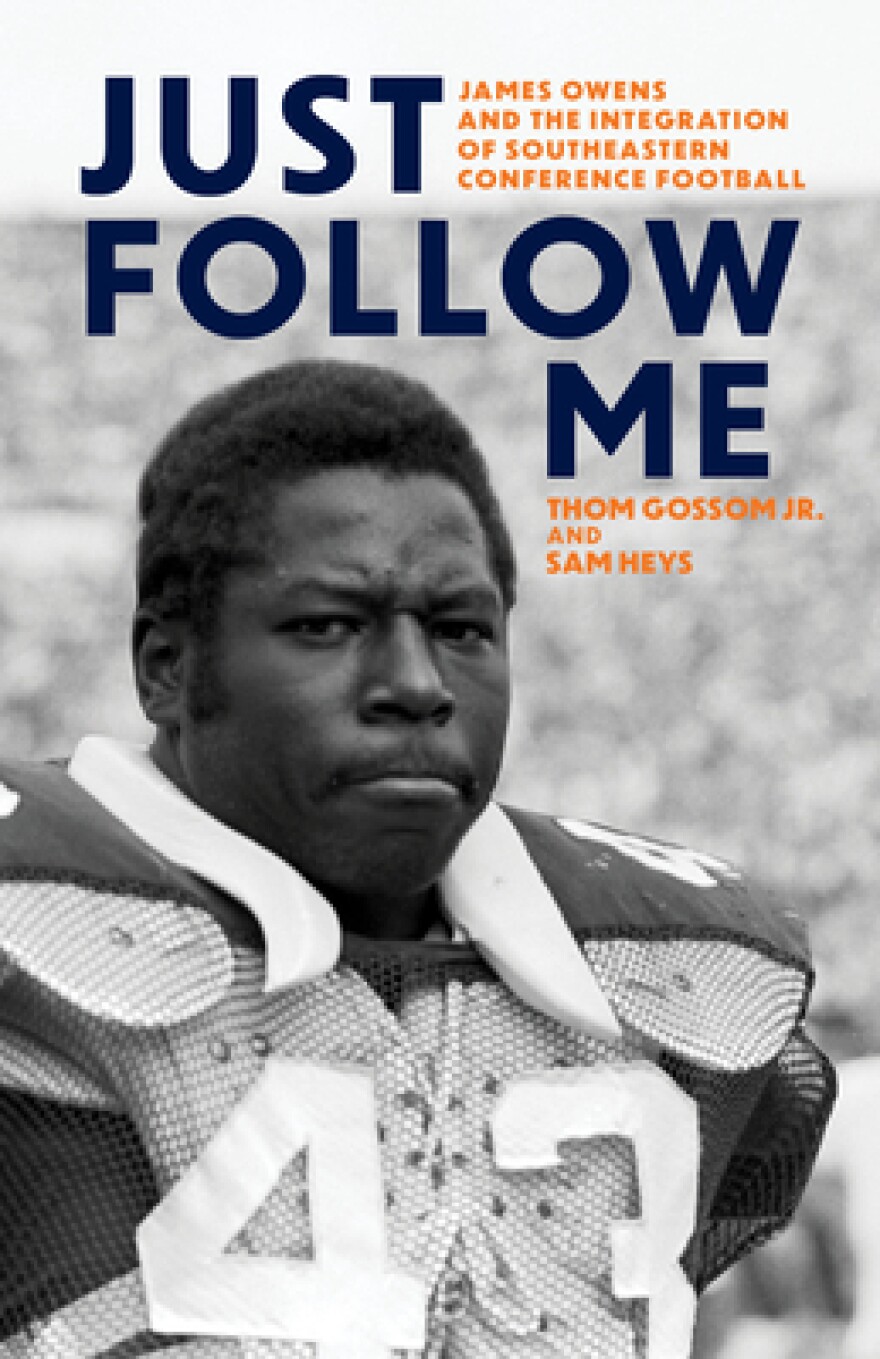

In August of 1969, Neal and Eloise Owens drove their 18-year-old son James from Fairfield, where James had been a football sensation, to pre-season football practice at Auburn University.

James would be the first scholarship Black football player at Auburn. He would be one of 149 Black students among a student body of 14,000. Owens had been preceded by Henry Harris, the first Black scholarship basketball player. His freshman year, Owens had a roommate, but in his sophomore year he and two other Black football players each had their own rooms.

The pressures were enormous, to be a trailblazer and not disappoint the Black family and neighbors who were rooting for you. The authors put it this way: “ …playing football at Auburn was easier than living at Auburn, or going to class at Auburn, or walking across Auburn’s campus.” Students stared; some shouted racial slurs. There were few African-Americans to socialize with, in Auburn proper, no place to get a haircut.

Heys, author of a book on Harris, and Gossom, who played at Auburn a couple of years later and was the first Black scholarship athlete to graduate, suggest that it was as if the University had admitted Black students and then said: “You people are here. That’s what you wanted, so be happy and shut up.”

Auburn, and for that matter the SEC in general, did little to make life tolerable for these students. They needed information, communication, emotional support, counseling: instead they got “the initial stages of White backlash over integration.” Some of this we might call history or sociology.

There were some elements that were specific to football, however. Owens was a big running back, 6’ 3’’ and 224 pounds. He should have carried the ball 20 times per game, but was instead made into an admittedly ferocious blocking back. This was a bruising position, making a hole for the fullback, but he did it brilliantly, in fact the title is a kind of pun. During a game, he told fullback Terry Henley “Just follow me.” Also, as one of the first Black students, he knew others would follow.

Like many Black athletes, Owens did not graduate. He tried to meet requirements after eligibility ran out but was not given adequate financial support. To support his family, Owens would coach at Miles College, work in a mill and as a janitor at Tuskegee, and then at 45, find a calling as a pastor at Pleasant Ridge in Dadeville.

Auburn did finally honor Owens 40 years later, with the Courage Award, named after him, and an honorary Bachelor of Humane Letters.

It should have been a doctorate.